CONTACT

Custom Lane,

1 Customs Wharf,

Edinburgh,

EH6 6AL, United Kingdom

mail@aefoundation.co.uk

DIRECTORS

Nicky Thomson

FOUNDING DIRECTORS

The AE Foundation was established in 2011 to provide an informed forum for an international community of practitioners, educators, students and graduates to discuss current themes in architecture and architectural education.

ANGELA DEUBER

ADRIEN VERSCHUERE

︎︎︎Samuel Penn

ANDREA ZANDERIGO

︎︎︎Rowan Mackinnon-Pryde

VALUES

SP

This session is split into two parts. First Angela and Adrien will outline a proposition on Values for discussion, and after, Andrea will give a short talk on Beauty. Adrien, over to you.

AV

Thank you. The idea is not to give a talk about the buildings we’ve designed; we could maybe do that some other time. But it’s more to address the issue of values, and maybe not directly, but more indirectly, and I hope that the talk we have together will broach this issue. So I’d like to address three things that I think are relevant for practice as an architect. They are not dogmas. They are just positions so we can discuss them later.

The first would be that architecture is mainly about ‘building narratives’. Architecture is essentially an act of thinking. It’s not about doing things ourselves, but rather doing, so others can make things happen. A large part of our activity is then ultimately about anticipating the real working in some kind of a fictional context. Our tools, words and drawings, help us to build our thinking through speculative fictions. In this sense, we could understand architecture as part of a larger artistic realm, like any other form of art. Making buildings, through the medium of space, is also for an architect about the construction of abstract signs, the construction of meaningful elements. Sometimes these signs act as traces in our personal memory. They could even be shared by a community and become then part of our collective memory. Place and memory share a lot together. Not only because they both act as complementary devices or structures, but also because our practice is ultimately engaging memories of existing situations that interfere with the way we think new ones. Architecture derives from iterative approximations, from metaphorical interpretations. Beauty lies in the possibility of multiple understandings.

My second point is ‘the constitution of choices’. Although it is very clear that buildings are only possible because of certain contemporary conditions, architecture has fundamentally to be understood as a timeless act. Our contemporary interpretation of existing buildings, whatever their own story, makes them, implicitly or explicitly, part of today’s way of thinking. Beyond the construction of a building culture, history gives us a fantastic repertoire. Without any kind of nostalgia, these precedents act as an incredible potential to reformulate narratives, by means of new compositions. Architecture is a performative form; it does not make sense for itself. Architecture consists essentially to build new relationships between people and things that exist, as they exist. Building new paradigms by means of new proportions. Architecture enables us to make critical choices, sometimes political, always rational but nevertheless subjective. If the architect is responsible for new organization of living, the nature of his choices constitutes the content of his proposal; it contributes ultimately to provide new values that go beyond the specificity of uses or contexts. Beauty lies in the dynamic migration of choices.

The third point is ‘the inefficient logic of means’. Architecture is a personal transformation of concrete observations. It is perfectly useless to know something that I could not modify. A project is always the construction of knowledge that would not only help to understand better our world, but mostly figure out the relevance of our choices. This process implies necessarily a personal point of view that goes beyond the self-will of the individual. The pragmatic use of observations tends obviously to an economy of means. Proportion, dimension and scale plead ultimately for the quality of this economy. Beauty lies in the inefficient logic of means.

AD

Beautiful music, like architecture, can connect people who have no common language, culture, neither past nor future. The search for beauty is what has brought me into architecture. In architecture the word beauty is almost not available. But I am driven by the search for beauty. Every time I experience a wonderful building. I think for example of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. It inspires me to continue my engagement in architecture. “Beauty is the name for something that doesn‘t exist, a name I give things for the pleasure they give me.” as the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa says, because beauty is the name for something that doesn‘t exist I want to explain five architectural terms which are desirable qualities for me.

The first term is ‘physical presence’. It’s like a starting point, a basis. With physical presence I mean the strength of the corpus, the bodies that surround us; physical means corporeal. Presence means, what is there, or the strength of the presence. I’m talking about the boundaries that make up a space. These limits have to have a corporeal strength. The basis for the physical lies in the material. Architecture is, if it is built, materialised. Each material has a unique regularity, a right and a wrong. My intention is that we should understand which opportunities are inherent in the material, and then to build with this knowledge in the physical present. Physical means that the surface is the material behind. The surface is a result of the material as it is built, as it was thought, and should not be scenographic. Architecture is simultaneously an act of an idea, the concept, and the construction. Not the poetic construction, in the sense of a symbolic construction, or a detail-story. It is more about building with the material, the means to develop and to think about details and the structure from the material with simple rational, mathematically, logical conclusions. If the surface is thought about as the material that is behind, the surface will let us understand the construction retroactively. We live in a time in which it is almost impossible to understand how something is made. We should be able to understand this intuitively in principle, even as novices. The construction should be as simple and unsophisticated and intuitively understandable, comprehensible and logical as possible. The boundaries, the surfaces, the colour, the material should be a logical result of the material used. The way in which something is joined should suit to the material; it should be logical and pragmatic. Presence creates identity. Identity is important. Identity means to find ones way, in everyday life, in ones environment and in the world. We remember architecture that appears strong, striking and distinctive. Strong architecture can provide a place, an object, an interior space with its own identity. Architecture can be a strong opposite and still influence us.

The second point is ‘the interdependent whole’. By interdependent whole, I mean that the whole is complete and that each element is interdependent on each other. To be dependent on each other is a condition. To be a whole means to be unhurt, unharmed and complete. A whole is understood as the combination of all components. This means in the physical sense, integrity, actual determination and perfection. If I talk about a whole that is interdependent, I mean that nothing can be taken away or added to the sum of all parts. I want my buildings to be whole. Architecture should be physical present and a whole that is interdependent. This leads us to structure. If we imagine an arch, every stone gives the load to the next stone. The supporting structure and the spatial structure is identical. The supporting structure is a fundamental component of the architecture. Without thinking about the supporting structure it is not possible to think about a building. The nice thing is that there are very precise logical criteria of statics, which make a form. It is an exact science. Most decisions in architecture are not an algorithm, are not clear and executable action-rules that lead to the results. So I think we should be grateful, that there is a right and wrong in architecture. We should use these for the architecture and not work against them. The fragment or the implied space: a whole implies the fragment. Only if one has something that is a whole is it possible to have a fragment of it. The fragment lets us retroactive know something about the overriding whole. Within this whole I’m always looking for the break of the whole. I call it the break of the rule. The whole should be perfect and imperfect, because perfection is inhuman. The claim that there is a greater whole which is interdependent in itself leads to the question of the perfection. Again Fernando Pessoa: “We adore perfection because it is out of our reach; if we would reach it, we reject it from us.” Perfection has something oppressive. That’s why the fragment, the first and the second structure, the break is important. The break of the whole is something beautiful. In my architecture I’m first looking for perfection and then I look forward, by finding natural given problems, to making the perfection imperfect and human. The break of the rule contains the question of how we can, in an equalised society, make architecture without being arbitrary? Because it is important to reflect on architecture with rules, especially today where everything seems to be possible. We should think about what this rule is, and the imperfection, the break, and what thought is behind it.

The third point is ‘the optimal, minimal and poetic space’. With optimal, minimal and poetic space I mean to think of architecture as space from the beginning, optimal for people, for the program, minimal means to build adequately, pragmatic, economically and not more than we really need. Poetic is a dream; the definition, sizing, disposition, joining and formal design of spaces is the main task of architecture. Architecture without space is unthinkable. In a space a piece of life is directed. A space can be the backdrop for a work of art in which a piece of life is staged. One can imagine here a society or a person who are staged in a room in a given time frame as in a play. At the beginning of the space is a longing, a desire. In the beginning is imagination; it’s a feeling, a dream, a desire, a wish. Out of this, the building develops. In a purely conceptual design, the project is developed by itself. A concept is a rule without poetry. I favour an unnecessary beautiful space before a functional one. To make a beautiful unnecessary space, is more than what we can understand and more than what we need. Every space can be its own universe. We can think of beautiful spaces regardless of what happens in the next space, but starting from what would be nice, at a certain time in the year, at a specific hour, in a very specific place. The basic question is the how we want to spend our lives. Architecture is the backdrop. The essential factors are the cardinals, the light, and the orientation in space, the view and the atmosphere that should be in a room. Each room can be thought of as a world of its own as a separate universe.

The fourth point is that ‘to create and to construct need to be inseparable’. I am totally against the separation of the idea and execution. Architecture today is defined less by beauty than it is by ugliness. We should begin architecture with a longing, a desire, a thought. We have gotten lost in the complexity of architecture. Architecture is the backdrop for a piece of life for a society. When we build in the narrower sense, at the same time we build our life in the wider sense. We should take physical boundaries seriously again. Most things we build make our environment, not better but worse. Construction is an underestimated and intrinsic part of architecture, but since we no longer build with our hands, construction has become indirect, remote and alien. My work is an attempt to escape this alienation. The baseless separation of the idea and the execution degrades Architecture. To create and to construct need to be inseparable. As architects, we have a great responsibility in society, which we should take more seriously.

My fifth and final point is ‘the myth of the idea’. I conclude with an overall reflection on architecture. We can ask ourselves whether architecture is a pure building that is beautifully designed? Architecture needs more than just material specific thinking. A building may physically hold together, but if there is no spiritual support, it cannot exist in the course of time. A building must be physical and mental. But with this spiritual support I do not mean the idea, which means in common parlance, that something is never completely realized, or simply a lucky thought, or simply a difficult term. I am against the myth of the idea. A myth is something we heard so often, but don’t know if its true. The term ‘idea’ is misleading. I notice my students make meaningful and very beautiful projects, if they are searching for a specific target. Then they have a dream, an image, a feeling, a thought, they follow something they are personally interested in and fascinated by. The mistake is to think at this point it would be done. After this point, the challenge is to realize the immature new, to work out a solution. We first need to know everything about a possible project and then think about ideals and then think it through freely. We produce good, mediocre and bad, we have to sharpen and deepen our judgment to discard, to select, and combine all thoughts together to one thought that makes sense. It is obvious that the ‘anything goes’ ticket is anything goes for ugliness in the world. Architecture must make sense and something makes sense, when we realize coherence. We are fulfilled, when we see a multitude of correlations.

AV

As I said before we voluntarily presented our ideas as something a bit dry, but also to be provocative about certain things. The first thing I’d like to look at is ‘choosing’, since as architects we mainly make choices, like other people also, but what would be the reasons for these choices, and ultimately choices interfere with the idea of values, since I believe that the choices we make have something to do with content of values you made in the introduction. So I would maybe address you, Angela, to explain a bit about these choices, because you were talking about the interdependent whole, the value of holding things together. Could you tell us a bit more about this?

AD

For me it’s quite important to build something that’s an end, which is a whole, but at the same time it’s important for me to break it. So, why do I want this? When I look around in Switzerland there are so many things that are built which don’t make our environment much better. They’re very arbitrary and random. Maybe that’s why I have this wish to make something strong, which is a whole. At the same time I know that we’re living in the 21st century, and I don’t want to make something overpowering. It’s a balance, how we can make, in our time, architecture, a city, a building, which is strong but at the same time, human. I guess what the whole is, is clear, or?

AV

I guess we also somehow address the same issues that if a building is about responding to certain realities, like a site, economy, or use, that is of course maybe a starting point, or maybe not even a starting point, but like elements, that we work with as architects, these are things we do, but it’s not enough. And this also relates to the choices we make, where we start, of course by bringing attention to economy and the means. Is this close to what you call values?

SP

Are there any shared values between architects today? You both talk about the performative aspect of architecture. Whether it’s a value or not is another matter. But you both talk about architecture as a backdrop, or something that allows the staging of life.

AD

Maybe I can start. When I talk about the backdrop for life, for me it’s especially about how you design a building. You can think conceptually, with rules, for instance, a rule would be, I’m in Edinburgh, and at each traffic light I will turn right. That’s a rule. It leads me to something without poiesis (to make). It’s a way you can develop a space in plan, or as a concept, or as a grid. You can also develop it out of a perspective way of thinking, the way Greek city planning was conceived. That’s what I mean by a backdrop or a stage. Because I can’t think of all the moments of a building at the same time, so I have to focus on main points. It’s kind of a picturesque thing, even though I don’t like the picturesque. There should be more to architecture than just a concept, more than just rules, it’s important to have them to enable you to work clearly. I think to imagine architecture from a personal point of view, and asking the question: how do I want to spend my life? We have to know this as architects. Of course architecture is for a wider society and it has to include the art of boredom. I call it the art of boredom. It should be calm and open to interpretation. Architecture is not like art where you can choose what to put in a museum. Everybody has to deal with it; it concerns everyone. We grow up in houses, in buildings. It’s a public art.

AV

The thing you said about interpretation is very important. I think we both agree that we should try to define a strong moment, moments of intensity, but I wonder if these moments of intensity are really related to the way we live, a way of living. If you look to the past you will also see that it’s about interpretation. You know, architects one hundred years ago built a certain way, with certain values, but we are still able to live in their buildings, and more importantly we can interpret their architectural choices. I don’t really see the architect as the only one who controls the choices about how we live. We are only there to start the story and then there’s a long story after we did our part. I think the choices we make are very relative, that’s just what I wanted to say. History also shows us, I mean, we were talking this morning about Aldo Rossi, and he quite clearly showed that a building can transform itself, a building can have different meaning in time, so this is more the way I was trying to address this, as a performative form. It’s a moving (temporal) way to understand and to live in a building. It’s not something that’s superimposed from the bottom. It’s static somehow.

PENNY LEWIS

I’m interested in this idea of strong architecture and weak architecture. Andrea Branzi says we live in a period of weak urbanism, and you Adrien are characterising the architecture of today as weak architecture, and then occasionally there’s strong work, and you Angela are saying that to make real architecture is to make strong work. Neil Gillespie and I were talking about this because we were having a discussion about Peter Cook criticising architects in London who produce a lot of brick buildings. He sort of dubbed them the ‘biscuit boys’, kind of saying that their obsession with building, detail, where a window sits, a kind of obsession that we associate with Switzerland, if you control nothing else, Neil says, then through brick you can at least control the building process. If we have weak architecture in Britain, which I think we do, certainly weaker than in Switzerland, or at least it feels weaker, then is building the actual act of realising the idea as an integrated process. Is building the best mechanism to guarantee strong architecture. Is a preoccupation with building the only way you can make strong architecture in the current condition, because it feels like that’s the world we live in. The best work is being produced by people who are very preoccupied with the integration of structure and the delivery of the product, if that’s the case, then the idea, I know you have a problem with the idea Angela, but the idea used to be something we got excited about, then we have to put all that on the back burner because building is the only terrain that’s left. I’m interested in what Neil thinks about that, but I think everybody is probably thinking that at the moment in Britain, is that the only means to control is to create strong buildings.

AV

We should talk a little bit more about what we mean by strong buildings. Personally I don’t see it as something especially radical, massive or robust. We were talking a bit about resistance, and for me a strong building is a building that can resist, responding to certain issues, the site, the economy, the social context, but resisting is also about time, and it’s not only about what we call pérennité (sustainability) it’s not about being robust so that it survives through time, but for me it’s also a question about memory. Is the building capable of addressing issues that people can recognise in the building throughout time? This could perhaps be a first definition of what we call a strong building. It’s about the resistance. It has nothing to do with the kind of radical architecture that we can see today. That’s the way I would consider it.

SP

You talk about memory, not inasmuch as you interpret memory to create a building but more that it creates memory?

AV

This is a nice issue I’d like to maybe address because the idea of memory is both about how you make the building, and maybe we can come back later to the idea of repertoire, of reference and of experience, but at the same time it’s also as a result something where everybody can project their things on to, and I still believe that if you go through cities, if you go to Milan or to Venice, it’s not only because people told you to go there, but it’s also somehow a way to meet memory, not only because we like old stones, but also because we identify ourselves to the particular values of our surroundings.

AV

Can we go to the idea of structure Angela? Because this is probably also an issue we share. So, the physical structure of a building, can you maybe develop the idea a bit, how you work with the topic, how you consider it?

AD

Structure is something that can create identity, it can be corporeal, something physically present. But at the same time it allows the programme for example, it allows us to be very open, to be very flexible. I have this example, the Palazzo della Ragione in Padua; it’s a Palazzo in the city. It’s an enduring timeless element that is not defined by the programme. The programme changed over time and after the site, the site lasts even longer, the structure remains. It’s not something we should over-value. I don’t like architecture which is just an engineer building, because it’s there that the interpretation is missing. It shouldn’t be the pure result of what the engineer says. I don’t want to build bridges, I want to make a building where the structure has an important part, and when I talk about this it’s not only the supporting structure but also the spatial structure or how the circulation structures something to give a certain clearness or calmness. When I was studying for example, Louis Kahn was the only one we could find in the library who wrote about monumentality, and I don’t mean we have to build monumental buildings, but with the structure there is a good opportunity to make both; to create identity but also to build something in the 21st century which is quite open and allows a lot of reactions. I don’t even want to control, to tell the user where he should put a wall.

AV

The structural issue is also interesting in the way that it is very precise, I mean this is the way we like to work with structure, because it’s very precise and somehow very objective, but at the same time it’s abstract enough to think about other things. For instance, in our practice, this is often a question we raise with clients, because it’s precise enough so we can talk about materials, and we know that when we talk about the structure it’s often defined as the physical structure, it still leaves a lot of space to talk about other things without necessarily talking about the whole project. One of the obvious things is hierarchy, because the structure defines what is first, what is second, if there is a hierarchy in what you want to propose. I guess it’s also a tool; a very clear, objective device to make the articulation between the dream you talked about Angela, and reality. It’s a bit trivial maybe, but in Belgium, or in Switzerland also, you know that when you do a building, in terms of budget, it’s more or less one third, one third, one third. One third goes to the structure, one third goes to the technical facilities, and one third goes to the architecture, and that already gives you a reading, an understanding about the reality of the architect. I mean, we can talk about energy afterward if you wish, but for a client basically, two third of the budget is not a discussion anymore. You want to have a building that stands. You want to have a building with ventilation systems, heating and whatever. So the only discussion we can have is about the other one third of the building, and this is why I think we should engage again the structure and also the technical parts of the building, because otherwise our spectrum is getting narrower and narrower, and of course the reaction of the client is to question the materials of the floor, not even the lighting system, but the curtains, the type of glass, the amount of glass, and I think this is the reality of the profession. If we accept it as it is then I think we are trapped. This is somehow my dream, to be able to think about the lighting system, or the ventilation, or all the things that is not part of our discussion anymore. I mean I’ve never heard of a client who asked the structural engineer to look at his calculations, same for the ventilation—never.

PL

But Angela was saying that construction has become alien. I mean alien to the public.

AD

We are living in a world where we have to deal with a lot of layers. Layers of insulation that protect against wind, water, warmth and so on. It’s a big, complex, expensive way to create a space. If we could just build one layer of wall that could do everything it would be such a huge progress for everyone, for the client it saves money, for the architect, on the construction site, everybody would be happy again. So how can we get there? With the students that I am teaching we develop projects that are built out of one material, only one, and for us it’s real, but when people from the outside come it seems like unfinished buildings, but I think we have to continue with this, and I’m not saying that everyone should go there, but intuitively we should be able to trust our environment.

AV

In our projects we already managed to change the ratio to fifty percent structure and fifty percent architecture, and then there is the technical, but with the technical there is a drawn line because they are these big lobby groups that control things. But clearly it’s a dream.

SP

I’d like to ask you about the idea of repertoire Adrien. Your understanding of repertoire probably differs from the conventional idea of reference. I know that Angela is very clearly against the idea of references in her work, but you are much more open in how you interpret it. What do you think they allow you to do in the development of your architecture?

AV

Your question is obviously about the making of the building, but it’s also about the building culture. For me, I could not think about architecture without considering the building culture around me. I mean, for me architecture is not a pure invention. I know that some people maintain that it is but we all have our own way of living in space, I’m not talking about values, if there is good space or not good space, but we all have our own personal knowledge of those spaces, and beside this we have a whole history of architecture. I don’t believe in modernity for instance. I think that modernity is kind of a continuity of other things.

SP

And yet you’re comfortable adopting themes of modernity in your own architecture.

AV

I’m not saying we should not build without regard to the time we are living in. But we are still free to look back into history and to consider it. That’s what I mean by repertoire. Then the way you use it is personal.

AD

How do you make your choice?

AV

That goes back to the ‘strong’ building I guess. A strong building for me is also a building that is open, and open for my own interpretation, to do something else out of it. It’s not only because I love the building, but it’s also because I feel there is a possibility of continuity somehow, and I guess it’s not personal.

SP

But we are in danger of seeing the history of architecture as the history of form. What I mean is that architecture is produced in a specific context, time, space, resource and so on, and if we take as architects the purely formal aspects as our basis for continuity then we miss the complete tapestry, and it could in reproduction, even in interpretation be emptied of meaning, the original meaning it had when it was created.

AV

Or you reinforce other meanings.

SP

But then you must be aware of the specific meaning you’re aiming to reinforce? For instance Mies van der Rohe is a thread in your work. Either you think that some meaning from that period needs to be reinforced in the present, or as I was suggesting with Venturi today, Palladio tomorrow, the charge could be made that it’s just playing around.

AV

But it’s not finished. He had his own sources. I don’t see it so much as a historical thing. History is what I try to address in my work. As architects, to know things for themselves is not very interesting, I mean we are transformers, we transform society. It’s our idiom. History for me is the same. You were talking about your students Angela, our students they often see history as something static, and for me history is not static. This is why I said that I didn’t believe in modernity as a static moment. And of course I realise that there are certain ways of building, certain societies, context and so on, but I still think it’s a moving element.

AD

But I think you should try to reach a kind of perfection, not necessarily in the plan and section for example, but in how you do it, how you think it. Frank Lloyd Wright was ninety years old and thought that he’d never made a great building, or Alberto Giacometti, he was always searching.

–

AZ

It’s very difficult to talk about beauty, and luckily, because we also run a magazine called San Rocco we recently wrote a call for papers on beauty, called ‘Pure Beauty’ for the next issue. So, I’m a bit prepared. I’m not a theoretician. I’m an architect, and we always say that architecture is formal accumulation, formal knowledge. I will first read you some sentences from Hannah Arendt and her view on public beauty. Please forgive my English pronunciation and even more my German. It’s from Arendt’s essays on Kant’s political philosophy, a text from 1982. For us it’s fundamental to understand what we mean when we talk about beauty, and beauty in architecture specifically.

She says: “We have judgments of, or pleasure in, the beautiful: ‘this pleasure accompanies the ordinary apprehension [Auffassung; not perception] of an object by the imagination by means of a procedure of the judgment which it must also exercise on behalf of the commonest experience’. This judgment is based on that common and sound intellect [gemeiner und gesunder Verstand] which we have to presuppose in everyone. How does this common sense distinguish itself from the other senses, which we also have in common but which nevertheless do not guarantee agreement of sensations? The term common sense meant a sense like our other senses, the same for everyone in his very privacy. By using the Latin term, Kant indicates that here he means something different: ‘an extra sense, like an extra mental capability [German: Menschenverstand] that fits us into a community. The common understanding of men, tis the very least to be expected from anyone claiming the name of man. It is the capability by which men are distinguished from animals and from gods.’ It is the very humanity of man that is manifest in this sense. The only general symptom of insanity is the loss of the sensus communis and the logical stubbornness in insisting on one’s own sense (sensus privatus), which (in an insane person) is substituted for it. Under the sensus communis we must include the idea of a sense common to all, i.e., of a faculty of judgment which, in its reflection, takes account (a priori) of the mode of representation of all other men in thought, in order, as it were, to compare its judgment with the collective reason of humanity. This is done by comparing our judgment with the possible rather that the actual judgment of others, and by putting ourselves in the place of any other man, by abstracting from the limitations which contingently attach to our own judgment.”

So let’s say, it’s true that to appreciate beauty and the judgement of beauty is subjective. It’s even true that each time we make this subjective judgement of beauty, we should also always suppose the judgments of every other man, this sensus communis as Kant calls it. Public beauty then. I will start with Giotto, in the Cappella degli Scrovegni in Padua. The very specific moment, in which the power of the prince, the power of religion, is slowly decreasing, it’s being substituted by the power of the citizens, the power of the city bourgeoisie. In a way what is interesting in the architecture of Giotto is that he’s reusing what he knew at the time, elements from religious architecture, elements from the palace, but reassembling them, as in a sense, tools or devices, to enact public life, in order to make public life possible. Why am I telling you about Giotto’s attempts to invent the new public architecture for the rising city society? It’s a bit of a cliché but we now live in a moment when all this is in danger. For instance, take Milan station; the most public space in the city, through the introduction of automated turnstiles has become much less public. It’s not just about politics, or economics, which is pushing the substitution of the private sphere to the public sphere. It’s even due to the creatives that made this transformation possible; they pushed for it, say for example pop culture. During the 20th century after Modernism, pop culture was, in a way, only concerned with the private sphere, beauty in the private sphere. To the extent that even art started to monumentalise the private sphere. For example, Jeff Koons makes a classical sculpture depicting him and his Hungarian porn star wife, Cicciolina. So this private sphere, this sensus privatus is completely monumentalised and completely occupies what was once the public sphere.

What does this mean in terms of producing architecture, and producing beauty for the public? The figure of the architect became completely inscribed by these new rules. A famous example is of course The Fountainhead in which Gary Cooper interprets this pseudo-right figure, in which the creation of architecture is coming straight out of his head, in this completely personalised idea of producing architecture and beauty. Opposing this, we might argue in Manhattan, in a society that was extremely focused on the individual, American society at the turn of the century; even there it was possible to produce beauty, to produce the city, to produce architecture in a sort of collective act. The very famous firm from that period, which were responsible for shaping Manhattan, as we know it, McKim, Mead & White, producing architecture together, with a firm of one hundred and twenty employees, in a time when this was unthinkable, and even using architecture as a shared public knowledge, because they were importing drawings of buildings from the Renaissance, Roman buildings from Europe, and giving them to their employees in order to build and design the Manhattan of the future. Other occasions when this collective spirit emerged inside capitalist society, to some other extremes, hundreds of draftsmen designing aeroplanes in an Albert Kahn factory during the second world war, or the most corporate office ever, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill producing architecture as a real collective.

Obviously these set of tools are not immediately translated into projects because a lot of other things interfere with the production of architecture. At the same time you see this idea of architecture as shared knowledge, the idea that architecture can try to produce public beauty is something that we really believe and try to achieve in our recent project in Milan. It’s called Casa della Memoria, ‘House of Memory’, and it’s a bizarre building because it hosts five associations that are related to cruel fact of 20th century Milanese history, the partisans, the victims of the terrorism of the ‘70s and ‘80s, the victims of fascist and Nazi deportations. It’s an office, a public space where you can do lectures or little exhibitions, a gigantic archive of the history of liberation, from a war that we started, okay, but let’s say that that’s another story. It’s the story of liberation from the German occupation from the second half of the Second World War. It’s part of a much bigger project, a huge real estate development that has taken place in Milan over the last few years, by a developer called Hines, with buildings by César Pelli, KPF, Arquitectonica, Stefano Boeri. Before we were involved there was already a ‘House of Memory’ project that had been designed by Stefano Boeri. You may think it’s beautiful or ugly, but for me what was interesting is that in this project by Boeri, the interpretation of memory was all about transparency. It was really the modernistic interpretation of memory as a sensibility. He decided to run to become the Mayor of Milan, he lost, but anyway he decided to stop all Italian projects, so they did a competition in 2011, and all our competitors went for the very same interpretation of memory, openness and transparency. Our first thought was that this memory was extremely fragile and that it needed protection. So, we thought of the building as a safe. At the same time we understood that there was the need to convey this memory on the surface of the building, so the first thing that came into our mind were polyptych’s from the Middle Ages and early Renaissance, where there is an effort to present collectivity, a set of stories, all together, on a given surface. The Polyptych of the Madonna of Misericordia, by Piero della Francesca is a good example.

![]()

fig. 1

The Madonna of Misericordia

Tuscany 1462

Obviously the aesthetic is very different now, but luckily, Gerhard Richter is always there to help, not only in terms of aesthetic, but also in terms of how to tackle this set of memories related to such difficult events. There’s an impressive series of paintings by Richter. Portraits of the members of the Baader Meinhof terrorist group from Germany at the end of the ‘70s. What interested was that they are composed of small portraits, big collective scenes, and his signature blurring, for us was almost like saying that these memories were impossible to forget and impossible to remember, as if by blurring it made these memories more distant and at the same time terribly present.

The other problem, when you talk about the idea of trying to represent a collective memory, while in the Renaissance there was someone deciding what to depict, the prince or the pope, nowadays things are different, we’re in a democracy, so you need a sort of participation game in order to find the right representation. There wasn’t money to do it properly, but nevertheless, we did this participation game. And then there was the issue of how you combine a building with this idea of a collective portrait, and we found this amazing example: the National Library by O’Gorman in Mexico City, where this modernist building, an archive block, is surmounted by this the cosmogony of Mexican origins.

![]()

fig. 2

Biblioteca Central UNAM

Mexico City 1952

And then came the idea of framing, like the polyptych, and we found this building by Giovanni Muzio in the early 1930s, trying to adapt to the new language, to Rationalism, and at the same time not really being able to convey this idea of lightness, and fighting with it, and producing this fantastic hybrid building, a convent in the centre of Milan.

![]()

fig. 3

Angelicum

Milan 1942

Gradually our façade started to appear, as a framed polyptych, comprising portraits and collective scenes made out of terracotta, a traditional Milanese material. We made a proposal for the competition and won. We suggested a safe, a very simple form, and indeed the plot didn’t allow much more, so it’s a simple rectangle. Then we started asking ourselves how the plan could be organised. The answer came from different trajectories, because we had been looking at buildings like the ‘corn house’. This tradition of keeping the corn during the winter in the very centre of the city because it’s protected, and the idea that this building despite being a storage space has to be monumental, because the content is extremely precious. We found that extremely interesting. They are tools that enable public life, but are at the same time very minimal in their physicality.

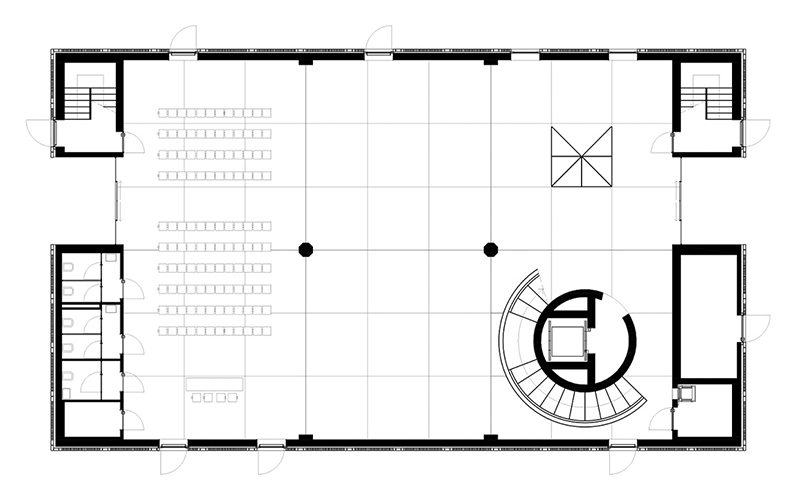

Another influence came from the traditions of the Venetian schools, which were important buildings, public buildings in the city, but second league monumental buildings. In the various neighbourhoods they were trying to establish some welfare, even trying to make local centres of power, and out of this came an architectural typology that is quite stable, a big room at ground floor with columns, and a monumental stair to reach the upper floors. This is the plan of our building which is very close to the plans of the Venetian school. A ground floor that is totally public, two columns and monumental stairs, and two wings for the services.

![]()

fig. 4

House of Memory plan

Milan 2015

We knew from the beginning that the budget was very low. We also knew the façade would cost quite a lot, so we have to be essential inside. We referred back to the essentiality of the Brazilian architecture of Villanova Artigas, and we imagined the inside as a dignified garage, very harsh, with idea of having part of the archive exposed, with a monumental stair which get’s you very close to the archive, which is closed because of the fragility of the content. I think we won the competition because the head of the jury was César Pelli. Apparently he entered the room and said something, which I think says a lot about the idea of public beauty, he said something like: “I really don’t like it. It’s really not my style. At the same time, if you want a house of memory, this is it.” After we were announced as the winners we started this participation process with the associations, which was a real effort, in order to define the set of images for the façade. And in studying how to build these images we developed this matrix of numbers, with each number being one pixel. There are six numbers for six colours of brick; four red and two greys. The portraits and scenes are made with a quarter of a brick, while the pattern below is made of half a brick. Then we started testing with a couple of mock-ups and we were happy with the result of this blurring, because when you’re close these images are simply disappearing, a pattern of colours, and you need a certain distance in order to perceive them. The only way to construct the images was to print the all the façades on paper and then to glue one square meter of this matrix on the insulation layer. The bricklayers had six piles of bricks behind them and simply built by numbers. It went surprisingly smoothly.

We were lucky with the contractor, with the way the engaged with the building, and they built in a very precise way, doing things that are not so common to do in Italy, maybe more common in Switzerland. They were so happy about the stairs that they really resisted the idea of painting it in yellow, and we really had to fight with them because they were saying: “Oh it’s so good like that, come on you can’t destroy it by painting it!” And we told them: “look, it’s a garage, if we don’t paint the stairs it’ll be even more of a garage, we really need to inject a bit of life there.” So they painted it, and in the end they were happy with the result, so I think it’s okay. I think it’s a very bizarre building, especially in that location, surrounded by these big new towers with a completely different idea of architecture in terms of what you could consider as being nice or beautiful.

![]()

fig. 5

House of Memory

Milan 2015

Photograph by Stefano Graziani

Let’s say, everything around is extremely fashionable, I’ll be nasty for a moment—in a very populist way. The ‘House of Memory’ is a very strange building, I think it’s quite difficult to know whether it’s an old or a new building, it seems as if it’s been there forever. It relates to the scale of the existing city to the north, to the late 19th early 20th century city made of blocks. At the same time it deals with the new part, from the south it appears almost like a pavilion in the park. Beyond our expectations, it soon became totally part of the city, really as if it had been there forever. I think the appreciation of it was unexpected. It became hugely popular quite quickly. Hugely, I mean, we’re not talking about the Bilbao effect, but with respect to the size and ambition of the building. It’s still a garage. I have to say that a year later, since they moved everything in, and I have to agree with Angela when she says that architecture is a backdrop for life. After one year it’s totally filled with all the gadgets from the associations. So there are flags, there are portraits; there are ugly sofa’s everywhere, the building has supported, quite decently I think, this invasion, probably because it is almost like an empty shell. Being an architect, as I said earlier, the only way to talk about architecture is to talk about projects. That’s why I decided to present this. It’s even the way we write San Rocco, each time we develop a call for papers, which is in the end an editorial, but at the same time the whole magazine is built up around cases.

RM-P

One of the reasons we wanted to talk about this subject today is because there’s a general pervading culture of not wanting to talk about it, that to have an aesthetic outlook is maybe a bit out-dated and conservative, or even luxurious in some way. Roger Scruton says we don’t talk about it anymore is because we’ve lost faith in ideals. Koolhaas says it’s boring and you’ll only get boring answers. Another aspect, going back to your Arendt reading on Kant, where it’s seen as undemocratic to make a judgement because it presupposes that there’s a right and a wrong, and that it might be a criticism of another individual who should be free to have their own ideas.

AZ

I think, maybe I’m oversimplifying here, but in a way the Enlightenment and Modernism basically killed it, killed the possibility of talking about beauty. In the best case Modernism substituted the discourse on beauty with a social agenda; Hannes Mayer for example. In the worst case they substituted it with efficiency, everything you could measure, efficiency is measureable, it’s the scientific paradigm in a way, while beauty is part of a different paradigm, it’s a totally human science whatever that means, and as such is not measurable. Even Kant or Hannah Arendt are not of great help in this respect. They show you something, but they don’t necessarily provide and answer. What they say is extremely ambiguous. I think it’s just the way human culture developed after the Enlightenment, but I think there’s a crucial moment; Vignola going to Paris to work for the king. There are these diaries in which, a very old Vignola, is talking with the king and with the new architects from the Enlightenment, and Vignola is simply, and continuously in a stubborn way saying, no, we have to do it like this, because to do it like this is beautiful. And the Enlightenment boys are saying, no, because we can’t feed the horses there and so on. It’s very nice to read and I think it’s really the moment in which you have this clash of very different ways of understanding architecture, or at least of understanding what the priority is in architecture. I’m not saying that efficiency isn’t important. I’m saying that the ‘programme’ is hosted by a building. It’s not the main reason why a building is shaped the way it is. As we all know, buildings all came from very different programs throughout history, so in a way, if you understand form as the main quality of a building, the main characteristic, then beauty automatically becomes the priority, because form is the only thing that will never change. The installations will change in twenty years, but form is there forever.

RM-P

I find the idea that Modernism killed beauty difficult. I’m interested in something Angela said about the whole, that you couldn’t add or take away but to the detriment of the whole, and the Modernists talked about this idea in their preoccupation with reduction and finding the essence, dismissing decoration as superfluous. Is there a relationship between this form of abstraction and the decorative references used in your work, especially in the House of Memory?

AZ

It’s a very difficult question. I think if you understand architecture as a fundamental part of the city, quoting Rossi’s Architecture of the City, I think that decoration was always a very powerful tool in order to signify and understand the hierarchical side of the city. Because, even in a very literal way, the house of the rich is a little bit more decorated than the house of the poor. The more decorated church is the church in which the believers put more money, and so forth, and I think it’s not irrelevant to how you as a citizen are then able to read the city, and to grasp immediately the values of a city. And now these values are in a way built up in an ensemble, with all these architectures that are there. On the other hand I agree that it’s not necessarily through decoration that you represent values and priorities, because it can be size, it can be mass, a peculiar structural choice. There are many tools, then it’s simply what you prefer, what you like, and what you like to use. I’m not for or against decoration per-se. I’m certainly not interpreting Modernism in a very literal or pedantic way. It’s not banned to talk about beauty; it’s not banned to use decoration. Decoration is probably one of the only areas in which the architect can still have a bit of pleasure. All the rest is such a big effort, to match the client desires, to be inside the budget, to fit the regulations, all the rest, drawing a plan, drawing a section, combining the complexity of the building into a difficult whole which is reasonable. It’s such an effort that finally you get a sort of relief in the easiness of decoration. But that’s very much from the side of the architect.

RM-P

If we’re talking about the decorative potential, is beauty then in the quality of the object, whether it’s the interpretation of the object by an individual, whether it’s in the moment, the event, or even if it’s in the idea. Umberto Eco says that an idea can’t be beautiful because it has no physicality, and that only mathematical ideas can be beautiful due to their relationship to the physical. Is that an important distinction? I find it difficult, as an architect, to remove aesthetics from the made object, because I think that’s the only thing we can control.

AZ

I think that beauty is an event. I think it’s an event that’s happening between the object and the observer, so you certainly need the object, and of course also the observer. It’s only happening in relation. Going back to Kant, it can only happen in the object, the observer and the mind of the observer in relation to all the other possible observers. If this is not the case then we kind of retreat back into the picturesque idea of beauty as a simple fulfilment of your senses. To me it’s a more appealing, or at least a more productive idea of beauty as the public shared quality of a given object.

RM-P

Are there any questions from the audience?

AUDIENCE

I have something to say. It’s a little bit about what you just touched on. You were getting to something about a shared collective values. If I remember my Kant, there’s something in there about universalising directions that beauty goes in, like there’s infinite ways to be ugly but there’s only one way to be beautiful. That’s obviously very crude. As you were saying, you’re interest is in the judgement of the viewer and not so much in the object itself. There’s something in that, when I judge this object to be beautiful, or when you do, somehow when you make that judgement there’s something universal about it and we all come together in that judgement. What I’m wondering though, is if you accept that we live in a multicultural society and there’s millions of kinds of beauty, then are there any other values in architecture that we might talk about that are universal. From Kant the thing about beauty is that it’s universal, and I’m wondering if it isn’t beauty anymore, not that it doesn’t exist, but if it’s become more of an individual thing, then is there anything that replaces it as a kind of universalised value?

AZ

I wouldn’t know what else in the end. To talk about universals now is becoming increasingly more complex. But at the same time it’s the only thing we should really talk about, universals on many different levels, the now fashionable discourse on sustainability is a universal discourse which is maybe a possible answer, but I would say a cheap answer, and still in the realm of efficiency, in the realm of something you can supposedly measure once you define the priorities, because it’s very difficult to define them. Beyond that I think it’s still only beauty that you can try to agree upon.

PL

Sustainability is a moral imperative but it’s not a universal objective in that sense. In fact it can be incredibly divisive. But beauty, and truth, which is the foundation of knowledge, and then from knowledge genuine democracy, to me these are the components of Humanism and a mechanism through which we could establish universals. We used to think that that was important, why do you think we took that off the table?

AZ

I’m not sure about truth. At least when you talk about human culture it’s about misunderstandings. Transformation in culture is always through appropriation, misunderstanding, or being dishonest toward your ancestors, using their words, their forms, their production and heavily manipulating it. At least in respect to culture, truth is very difficult.

PL

I would argue that you use Hannah Arendt as a framework, and her actual preoccupation is how you arrive at real knowledge and understanding of the world as a human being in relation to the rest of society. So when she talks about the public, she’s not just saying we want to hang out together in a public space, or even that we want to make a public building. What she’s saying is that we can’t make architecture, as an expression of our collective will now because we have abandoned the project of developing our knowledge and understanding of the world and our individual place in relation to society. So for her, truth, knowledge, democracy, are all intimately connected and she thinks that to develop knowledge makes room for public life and democracy, so in a way it’s not fair to use Arendt as a starting point and then abandon the project of what she’s arguing, because I think she would never have given up on the possibility of getting closer to truth, not to arrive at a truth and for it to be fixed, but for it to be an open process that’s related to democracy.

AZ

I totally agree with you. But at the same time Arendt was a much more serious person than any architect I know—laughs. She was really busy with the fate of humanity. Architecture cannot compete with that. But at the same time I still consider every act of architecture, even the most private one, let’s say a guy in a remote part of the country asking an architect to do something in his house, that is already a public act, for two reasons. One, it’s happening on the globe, which is still shared, and the other reason is much more interesting, if you call an architect for your little kitchen, you’ve got a public ambition toward that kitchen. As an architect you might want that kitchen to be published, and as such, even the most private act of architecture is by definition, a public act, and immediately enters the discussion about what is nice, maybe not what is beautiful, but certainly what is nice or cool. In that sense, I think it’s one of these professions that are still necessarily linked to the realm of the public, the collective, the shared, which is somehow an act of resistance. I think it’s an act of resistance on many levels actually. We all know that architecture is such a slow profession. It takes five, ten, fifteen years to do something. But luckily this slowness is even embedded in the object, and the object is there to stay longer than us. I think that’s an incredible act of resistance toward the atomisation and individualisation of our society.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()