ROWAN MACKINNON-PRYDE AND NEIL GILLESPIE

︎︎︎introduction by Penny Lewis

The following is an edited transcript of the event held at Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, in 2024 as part of the INHERITANCE series.

PL

Rowan is diector of STUDIO NIRO, which she directs along with Nicky Thomson. Nicky and Rowan met while working at Reiach and Hall Architects, the practice of which Neil Gillespie has been design director for 20 years.

The connection between Neil and Rowan is a formal one: Neil employed Rowan for a period of time. But it’s also been informal, which is I suppose what’s really interesting in that they’ve worked through a number of projects together and continued to discuss ideas.

Probably the most important thing, which is a source of great joy, is that at the end of last year Reiach and Hall and STUDIO NIRO made a successful joint bid for the Orkney Creative Catalyst project for the Pier Arts Centre in Orkney. They will be working together on that project for a client with whom both practices have already established relationships independently.

So there’s plenty of crossover in terms of experience and outlook, but we also hope that, on the subject of inheritance, there’ll be differences of opinion— there will certainly be differences in experience.

RMP

There is an element of this talk that’s about STUDIO NIRO and an element that’s about me. I’m conscious to avoid it becoming too personal, but I hope that through the personal, the general can be implied, or thought about.

The connection between Neil and Rowan is a formal one: Neil employed Rowan for a period of time. But it’s also been informal, which is I suppose what’s really interesting in that they’ve worked through a number of projects together and continued to discuss ideas.

Probably the most important thing, which is a source of great joy, is that at the end of last year Reiach and Hall and STUDIO NIRO made a successful joint bid for the Orkney Creative Catalyst project for the Pier Arts Centre in Orkney. They will be working together on that project for a client with whom both practices have already established relationships independently.

So there’s plenty of crossover in terms of experience and outlook, but we also hope that, on the subject of inheritance, there’ll be differences of opinion— there will certainly be differences in experience.

I start with an image of the model that we made with Reiach and Hall Architects for Orkney’s Creative Catalyst (figure 1). It’s really interesting to be working again together, if in a slightly different structure. We are two practices working together, with two different experiences of the place: Orkney; and of the client, the Pier Arts Centre, and their collection.

One of the first things that Nicky and I wanted to do with this discussion, is to make a distinction between ‘inheritance’ and ‘influence’. When looking at the word’s origin and its definition we think about the idea of passing something on, sharing. Sometimes this is a conscious sharing of material- perhaps when we know that somebody is particularly receptive to an idea or in particular need of a reference.

Related to the idea of inheritance is an idea about family- the suggestion of a common sense, or common set of values. This is our reference point when moving through this talk.

The discussion of inheritance in architecture gives the opportunity to question the idea of the sole genius or sole author, and perhaps puts into question the relationship between the individual and the collective. What does one project mean within a body of work? What does that body of work mean more broadly to culture?

The idea of intuition has been of interest to me for many years. What and how do influences infiltrate your subconscious and how does this influence one’s practice? Ideas can become so embedded that it’s hard to resist- for example, a way of drawing, or a way of thinking- because it’s become so integrated with your process.

How do we use our intuition to make judgments about our work, how do we decide when something is ‘right’? The Japanese have a term that I think captures this idea: Taru wo shiru, the knowledge of what is enough.

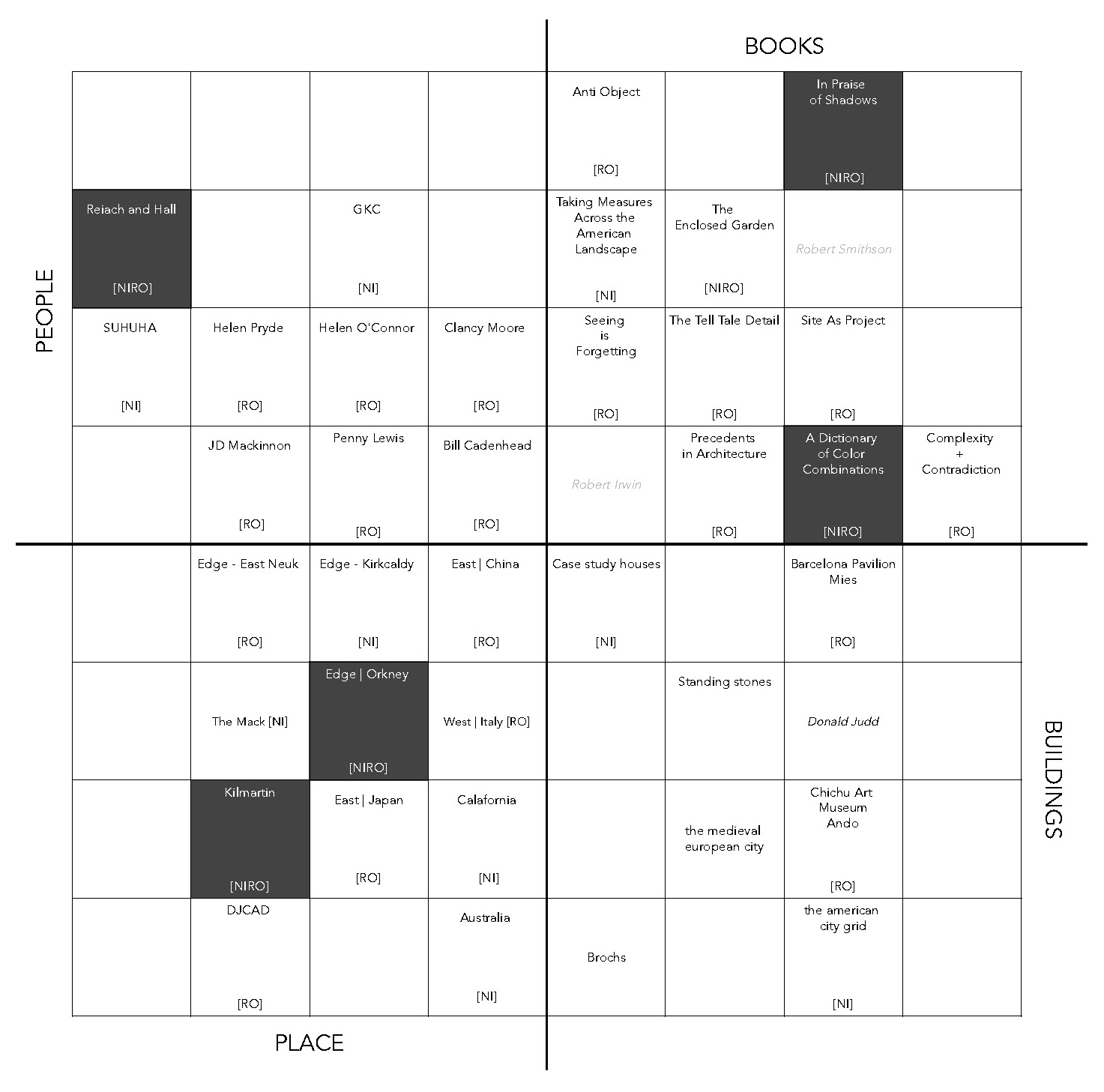

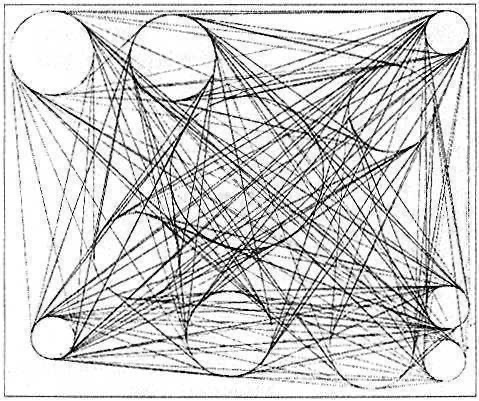

Nicky and I have thought about the influences that inform our intuition in terms of 4 categories: place, people, books and buildings and we’ve started to construct this matrix. (figure 2)

Figue 2. STUDIO NIRO Inheritance Matrix.

We’re two people- NI and RO. We each come from slightly different backgrounds and came to architecture from different directions: I came from the arts and Nicky came to architecture through an interest in geography, the social sciences and town planning. We trained at different schools, we’re slightly different ages, and have worked in different practices until, that is, we met at Reiach and Hall.

So there are differences, but then there are these overlaps, which, I think, possibly overlap with some of Reiach and Hall’s thinking, and maybe some of Neil’s references too.

PLACE

When we think about place, one can be influenced by the physical presence and material of place, but also by the ideas that underpin a culture of place. I know that my thinking, subconsciously, and then more consciously, has been influenced by some of the fundamental ideas of western classical culture. For example Plato’s realm of forms; the relationship between the real and the ideal, and the pursuit of truths that really can only be approximated- a frustrating reality.

There are references we draw on quite a lot, both in practice and in teaching, which relate to how we think about place. We often return to visual art references. We’re obviously very interested in buildings and we look at them, we visit them, we study them, but actually the references we often use come from fine art. I think it’s because they provide an openness for interpretation. We might use these with clients to talk about an idea without presenting an image of ‘an architecture’.

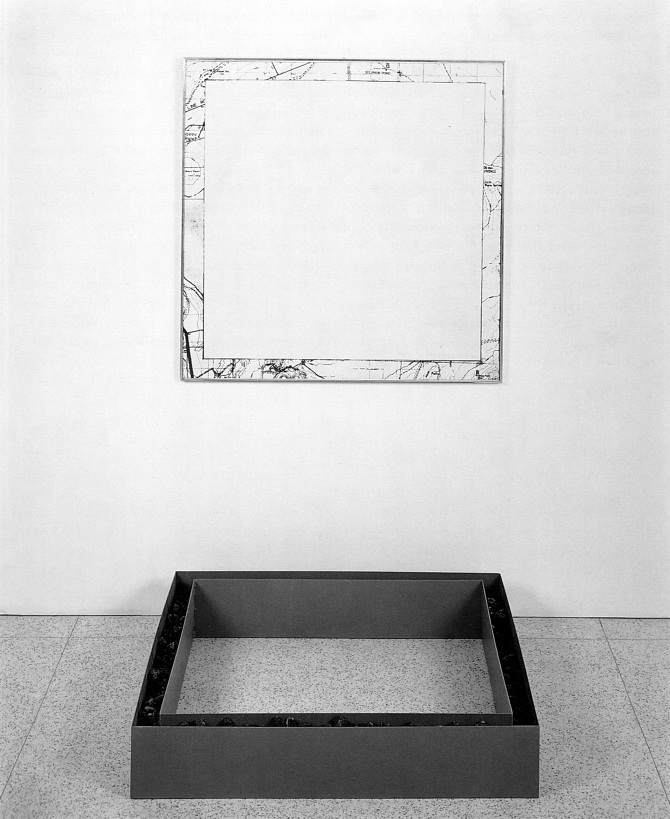

The artist Robert Smithson talked about ‘site and non-site’ (figure 3): site being the experience of a landscape or a place and non-site being a representation of that experience in another context. It’s not about experience or imagination in isolation from one another. The imagination of place is manifest in a spatial idea that exists in a real environment.

Figue 3. Robert Smithson, Mono Lake Non-Site (Cinders Near Black Point), 1968.

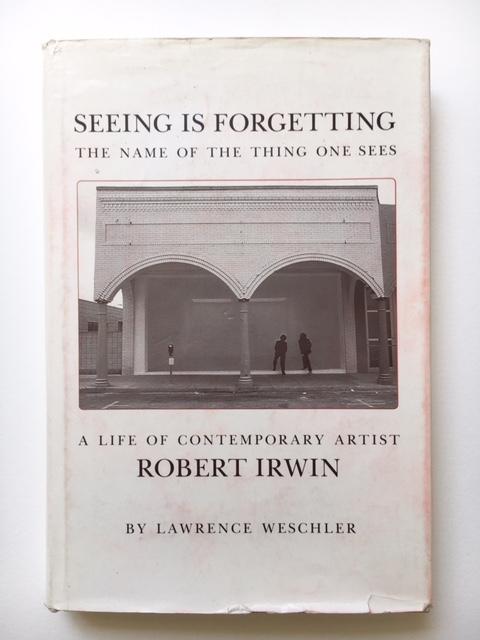

Figue 4. Robert Irwin, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, originally published 1982.

Figue 4. Robert Irwin, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, originally published 1982.As a student, Andrew Clancy, who reviewed the work of our masters studio, introduced me to the book “Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees”, a book on the artist Robert Irwin (figure 4). Irwin talks about the realisation he came to in his practice that the figure and ground hold equal meaning. Together these ideas can generate a starting point for a project. We’re interested in this.

We’ve reflected on how place influences formal ideas. We both grew up on the eastern coastline of Scotland, and I think that the horizon and the view across the horizon towards something else— another place— opens up a kind of optimistic recognition that there’s something else out there to go in search for. From a compositional point of view too, the horizon and the horizontal datum plays quite an important role in a lot of our work.

PEOPLE

People are of course influential in everybody’s lives. I recognise that the people most close to me growing up, my parents, were also my teachers in terms of spatial ideas. My dad was an architect and my mum is art college trained.

When I was around three or four years old, my mum and I would spend a lot of our time making things. We would go to the beach and collect stones and think about how they could become standing stones, then we’d compose them and set them in plaster (figure 5).

Figue 5. Beach found stones cast in plaster of paris, c1987.

Figue 5. Beach found stones cast in plaster of paris, c1987.

On another day, we’d visit the site of standing stones. I think this was not just about making something and having fun. Without being consciously constructed as a lesson, this exposure spoke more deeply of history, the traditions of making, the relationship these ancient structures have with the landscape. They speak about the way in which people made links to the land, solidifying ancestral connections to place, contributing to an identity inherited through generations. Even though we may have lost, or forgotten, the original function or meaning of these structures, somehow they’re still connected to our sense of cultural identity.

As a child my dad introduced me to the concept that architecture was about space, rather than objects. I remember being presented with one idea from the ancient Chinese philosopher Laozi. He used the analogy of a vessel— a bowl or a vase—and writes to remind us that it is the space of the vase that gives it value. The container, or the framework, simply facilitates that space.

It was through learning to draw that the notion of negative space was reinforced. I was also encouraged to observe order in the world. Nature had order. Order was about space and proportion— this is the kind of thing my dad would talk to me about.

He’d also explain that building design didn’t always have to be about a collection of rooms, but space could be organised through planar compositions— and showed me Mies or Frank Lloyd Wright.

Figue 6. Rowan Mackinnon-Pryde, Brass and acrylic constructions, 2003.

Figue 6. Rowan Mackinnon-Pryde, Brass and acrylic constructions, 2003.

So all these ideas cultivated an interest in spatial design which led me to art college. After a few years in the design department in jewellery and metalwork, (figure 6) I transferred into Architecture. But I was always interested in other disciplines and there was never any sense that I needed to become an architect. For my students too I don’t insist that the study of architecture has to be a vocational pursuit. It’s such a broad and rich subject that can lead you down many different avenues. This is fundamental to the founding of STUDIO NIRO. We wanted to practice ‘architecture, among other things’. We try to resist the idea that architecture is only the building.

Another important figure in my learning was a tutor I had at college, Helen O’Connor, who introduced to me the idea that the detail of building wasn’t just a technical thing, it had the capacity to communicate architectural ideas. The detail was the smallest component of meaning in a whole project— another classical idea. The relationship of part to whole is something that we always try to work with.

Preparing for this talk has been a really interesting opportunity to reflect on things that are important to me personally and to our shared work in STUDIO NIRO. Nicky and I spent the first couple of years of our practice thinking about what we wanted to do, what we are going to do and how are we going to get there- projecting towards the future. Then in the last year, we made a piece for the RSA Open Exhibition which was a kind of mini retrospective.

We took five years, five projects, five ideas, and wrote short essays on the values that we think underpin the practice.

It’s useful to step back. We don’t often have the opportunity to reflect which is why these discussions are so important.

SITUATION (figure 8)

“We begin each project- no matter the scale or medium- by defining its situation: its context.[...]

We consider the past and the present with equal curiosity, and allow both to inform a narrative which will lead to future speculations.”

Fig 8: Linkshouse Residency Centre Phase 1, Orkney, 2023. Credit, STUDIO NIRO.

ABSTRACTION (figure 9)

“In pursuit of something akin to abstraction we gravitate towards refinement and simplicity through a tireless process of reduction and rationalisation.”

Fig 9: Dichromatic Apartment, Edinburgh, 2021. Credit, Jaro Mikos.

INTEGRATION (figure 10)

“We believe in the continuity of an idea being drawn through a project. Design thinking expands as we follow the trail of a project’s logic. It could be said that the whole is prioritised over the parts; a unified aesthetic over an articulated moment.”

Fig 10: The Little Chartroom (restaurant), Edinburgh, 2022. Credit, Jaro Mikos.

DIAGRAM (figure 11)

“[the diagram is] a vessel for a project’s logic- a point of reference for the design process, informing decisions and communicating priorities.

It collects spatial, temporal and programmatic ideas, defining relationships of solid and void, rhythm and proportion, present and future, inhabited and attendant.”

Figure 11. Eleanore (wine bar), Edinburgh, 2021. Credit, Jaro Mikos.

SPACE + SURFACE (figure 12)

“We regard architecture primarily as an act of spatial composition, as distinct from that which is generated from an accumulation of materials. In lieu of material richness, material qualities: heaviness, lightness, translucency, are embedded in the project.”

Fig 12: VIth Form Centre for Nicholas Chamberlaine School, Bedworth, 2022.

Credit, Chris Pendrich.

Reflecting on all of these ideas— past and present— I’m interested in how this inheritance feeds into something bigger. How does it feed into the culture within which one works? How do we negotiate the tension between the individual and the collective— one person, or one practice, that is also contributing to some kind of ‘common sense’ about the world.

NG

First of all, I’d like to start with a disclaimer from Juhani Pallasmaa:

‘the verbal statements of artists and architects should not be taken at their face value, as they are often merely represent a conscious surface rationalisation or defence that may well be in sharp contradiction to the deeper unconscious intentions giving the work its very life.’

I think that’s very true and we’re giving a little talk here, but actually we probably mean very different things deep inside.

Figure 13. Eloquent Silences: Writings on Art and Architecture, Carlos Marti Aris, 2020

I’m influenced by things like this constantly: a book by Carlos Marti Aris which has recently been translated into English (figure 13). The title of the book is brilliant: ‘Eloquent Silences’. I think eloquent silences are an oxymoron: an eloquence and yet silence. I think he is a really significant critic and he says:

“if I have learned anything after so many years devoted to these themes, is that any attempt at theoretical construction in our field must from the outset assume an auxiliary role, a secondary condition subordinate to the works which are the true repositories of knowledge both in architecture and in any other artistic activity. This auxiliary character that I attribute to theory in the field of art in no way diminishes its importance, nor does it deny its decisive value.”

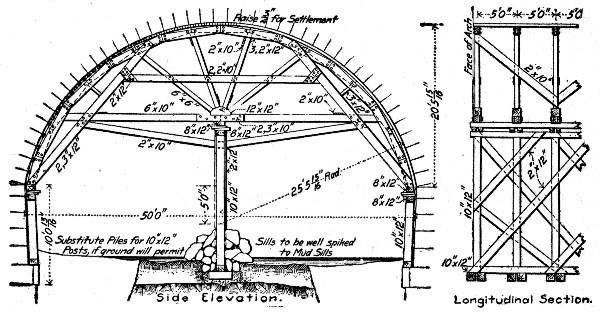

And this is where I’ve pinched the idea of the arch (figure 14).

Figure 14. Source unknown

It’s like the hangar that makes the construction of the arch possible. Once it’s mission is accomplished, it disappears. And it’s not part of our perception of the finished work, but we know that it was a compulsory and essential step— a necessary element to erect what we now see. So in other words, the idea of theory, the idea of inheritance is all very well, but it’s the formwork that creates the arch. And there are many arches, so that the formwork becomes very particular to you and the form of the arch is influenced by many things.

So inheritance is something which is passed down and it’s tangible and intangible. It’s about culture, morals, ethics, beliefs, history, geography, it’s about your family. It goes on and on and on. And because of that, it becomes very personal to yourself, which is why I don’t think you can avoid talking about yourself.

And thinking about that, I think there’s two types of thinking. There’s vertical thinking, which builds on something else, so it endorses a position, and it refines existing histories, patterns and understandings and involves repetition.

Horizontal thinking, or lateral thinking, is the opposite. It’s about disrupting accepted patterns and involves moving out or seeking out. And it seems to me that a healthy culture must have both of these. You must have something which is about the quotidian, about the daily, about repetition, about who you are, about what culture is. Then you can move out and create work which challenges that. But it always comes back to the centre.

I converted that into two types of space as well, a kind of imaginative space, which is the drawing. But then there’s material space, which is the important thing, which is the real thing. It’s the stone and the gravel.

I have a lot of poet friends and I like the idea that the poet of vagueness, that sense of space, must always be the poet of exactitude. That comes from Itallo Calvino. So in other words, to write a poem, you have to be immensely precise in your selection of words. And if the selection is correct, the space it creates is immense. So this kind of oxymoron of vagueness and exactitude is important.

There’s a brilliant scheme by Teresa Moller (figure 15). This path through these rocks and how they had to address each situation as it came, through skill and through application. And it’s taking those opportunities, finding that path. I think we need to accept that we aren’t free to move the way that we want to.

Figure 15. Teresa Moller, Punta Pite, Chile, 2005.

Another drawing that I always use is a drawing by Helmut Federle (figure 16). I would love to see this as a three-dimensional thing. These influences, which are the circles, or moments, or people, or buildings, or drawings, or projects- they’re connected. Some tenuously, some strongly. Some of them are important: big circle; some less so: small circle. But actually in time, if you were to move them, and these circles varied in diameter, it’s a project. It’s not linear. It’s a three dimensional thing where you’re moving forward, but you’re also referring back.

Figure 16. Helmut Federle, Konstellation.

And I think also the big thing about me, and I’m sure it’s the same with many of us, is coming to terms with your own history. There’s things that you will deny, but actually they are really important.

There are moments in your life where you forget to look back or to look forward or to the side. And I think that our culture at the moment is obsessed by what’s in the spotlight. There are many things which are in the shadow or in the penumbra which I’m attracted to. I’m always attracted to the shadows or to marginal architects.

And so my childhood experiences. Father was in the war. Last thing you wanted to do was go abroad. So we travelled in Scotland. The north is my imaginative space. I was reading things like Neil Gunn who wrote ‘Landscape and Light’, a series of essays. There’s an essay in there called ‘Highland Space’ which talks about the horror of the Highland void, this emptiness, this special thing. This is a brilliant piece of writing.

My brother Ross has the same sense of that imaginative space and that emptiness. He made some work which sits in one of our projects, Inverness Justice Centre (figure 17). The landscape was about simple things like a rowan tree or something like that. So that landscape was the quotidian. I’m always interested in this daily activity and this more expansive space, unknown to me.

Figure 17. Work for Inverness Justice Centre. ©Photographer Broaddaylight, Artist Thomas A Clark.

I studied that Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) under Andrew Jackson, a great tutor. The school was very much an east coast school. It was interested in the Scandinavian masters, soft Scandinavian architecture, materiality, thew simple plan. Arnie Jacobson was the great hero, not Aalto. Aalto was far too flaky, too inventive. Arne Jacobson was the man. And that you can see that in the early Reiach and Hall buildings. That was the culture of Reiach and Hall when I arrived.

Stuart Renton was Reiach and Hall’s design director at the time and he was a fantastic architect. He designed the New Club on Princes Street in Edinburgh and was acknowledged as one of the most elegant detail designers in Scotland.

He also designed his own house at Nether Liberton (figure 18) I think that facade is one of the best, not in Scotland, but one of the best in Europe.

Figure 18. Stuart Renton, Clapperfield, Edinburgh, 1971. ©Reiach and Hall Architects.

But you know, you’ve got to deny your father, haven’t you? You’ve got to deny the people immediately above, especially if they were employing you. And so what you did was you looked out and at people like James Stirling, Mario Botta, Louis Kahn. Anything but the Scandinavian guys.

I was based in London for a little while and the 9H Gallery was happening. 9H Gallery was introducing the UK to people like Siza. They had exhibitions that said ‘newcomers Siza and Eduardo Souto de Moura’ as if they were young, but they were, I suppose.

Herzog and Meuron were just beginning to make a mark. And suddenly I saw people that were really interesting. They were drawing in a very different way. They were drawing more like artists. It was visceral, it was intuitive. And then there was Rem Koolhaas. He was just throwing everything up in the air. The Kunsthal was an amazing project.

Then I started to seek people out. I sought out the artist Alan Johnson because I liked his work (figure 19). He instigated a gallery in the basement of Reiach and Hall called Sleeper.

Figure 19. Alan Johnson, Beyond the Flow, Pier Arts Centre, Stromness, Pier Arts Centre, Orkney, 2023. ©Pier Arts Centre.

At that time, we were doing projects where we worked with artists. One of the first that we worked on was Stills Gallery with Nathan Coley, in around 1997. We worked with Nathan again in 2010 on ‘In Memory’ at Jupiter Art Land. So there has been another vein of working with artists which was really interesting as well.

I went out with to Japan with Alan Johnson to help him do a project with an architect chap called Shinichi Ogawa. From that private visit to Japan there was an exchange arranged with the ECA. We visited Sesshu Garden. Kenneth White writes about Sesshu Garden and so does Neil Gunn. So suddenly this garden was bringing you Neil Gunn stuff that I’d heard from when I was 10. Suddenly there was something very interesting about that. It was about silence and stillness.

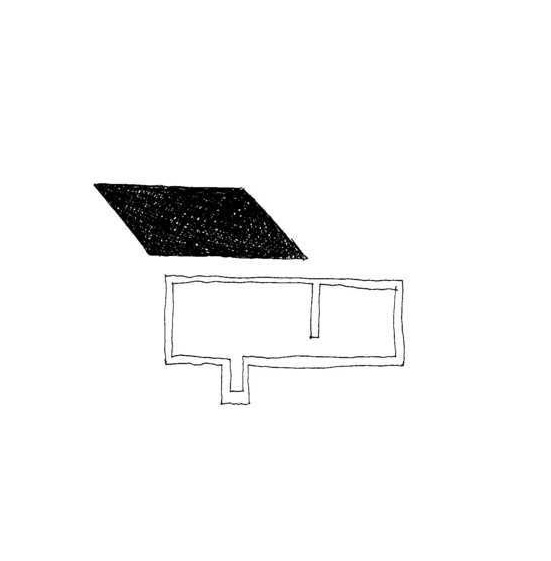

Roger Ackling gave rise to a bothy that we did for him (figure 20, 21). The idea was that the extension at the back was a shadow of the building in the foreground. But the extension is to the South of the bothy. So there was a notion of a Hyperborean culture. A culture, that suggested that all the Greek myths actually happened in the North and not around the Mediterranean. And so there was this idea that we would cast light from a northern enlightenment on the bothy and create shadow.

Figure 20. Concept Sketch, Ackling Cook Bothy, Reiach and Hall Architects, 2011. ©Reiach and Hall Architects.

Figure 21. Ackling Cook Bothy, Reiach and Hall Architects, 2011. ©Reiach and Hall Architects.

And finally, we did a house for Alan Johnson, which was a great thing (figure 22). It was about a Shinohara project. About embedding a crevice within a very simple building and the difference between space, which is about imagination.

Figure 22. Johnston House, Reiach and Hall Architects. Credit, Neil Gillespie.