CONTACT

Custom Lane,

1 Customs Wharf,

Edinburgh,

EH6 6AL, United Kingdom

mail@aefoundation.co.uk

DIRECTORS

Nicky Thomson

FOUNDING DIRECTORS

The AE Foundation was established in 2011 to provide an informed forum for an international community of practitioners, educators, students and graduates to discuss current themes in architecture and architectural education.

MARTINO TATTARA

GABRIELE MASTRIGLI

︎︎︎Penny Lewis

PROJECT

PL

The two speakers we have here this evening are going to talk for about twenty minutes and then we will open it to the floor for discussion. So please, through the event, please prepare yourself to raise questions, to make your own points or to pursue particular issues that you think are important. Our last lecture was by Pier Vittorio Aureli, and Aureli’s talk was so compelling and interesting to us – he was talking about urbanism – that we thought that we wanted to pursue the discussion further. So this evening we have invited two architects that we think will help us do that, and that have something very important to say in their own right. Martino and Pier Vittorio have a practice together called Dogma, based in Belgium. Before he speaks, and to provide some context for their work, and Italian discussions on architecture, Martino invited Gabriele Mastrigli, also an architect, critic and author, to join him.

GM

Even if architecture is a general and very common word, especially associated to something built, architecture as a procedure to imagine how to modify physical space, always changes when we move from one place to another and in history, because of the different conditions and contexts in which architecture operates. Therefore the meaning we give to specific words such as ‘project’ can also be very different and not so self-evident. We assume that the meaning of project is about making a prediction or anticipation for a future. In reality a project is first of all the superimposition of a new order on top of an existing condition. Or better, it is a negotiation based on the relationship between what exists and what will be superimposed. To project means forcing reality to change through a deliberate act, often violent. Not by chance words like ‘decision’, ‘definition’ and ultimately ‘design’, all implied in the notion of project, come from Latin and share the same prefix ‘de’ (off), that means to cut off, to separate, to isolate. Far before simply shaping the world, a project implies taking a position often against it. The famous image of Le Corbusier’s hand showing the model of the Plan Voisin is very emblematic in demonstrating how the project is about taking decisions. Architecture is always about taking radical decisions. That’s why that image has been so successful and replicated in the postmodern period even if the changing milieu had inverted the polarity; in one page from Koolhaas’ S,M,L,XL, the same act is describing the possibility of revealing something from the context, therefore implying that the project is somehow already embedded in the reality we are facing.

The work of Dogma is deeply rooted in the idea of architecture as a project, more than simply design. In order to frame it in a more general theoretical background, it is useful to go back to some aspects of the architectural debate in Italy in the early 1960s. It is in fact in that context that the notion of project is radically confronted with those of architecture, urbanism and the city. Since the late 1950s Italy is characterized by the explosion of the so-called affluent society. It is the richest moment in the whole history of Italy. This explosion, not by chance called ‘the boom’, is above all about the new dimension of the city, and the possibility of moving through it, transforming urbanity into a brand new experience. This condition is portrayed almost live in movies like Dino Risi’s The Easy Life, where the advent of economy cars represents the shift towards a society dominated by movement and by the continuous transformation of its physical structures. As the ultimate mass-produced and mass-consumed objects, cars represent at best the urban life of this society. New infrastructures, such as the Autostrada del Sole, the first big highway realized in 1960 to connect the North with the South of the Italian peninsula, radically transform the perception of the city and the territory revealing its more and more aggressive exploitation. As represented in Francesco Rosi’s Hands over the city suddenly architecture becomes a matter of quantity: just buildings, not designed or planned but simply realised, often in a climate of illegality and political corruption. This new generic condition of the city make architects and urban planners put into discussion the premise of their work.

Two books both published in the early ‘60s start to deal with these urban issues from two different points of view, even if sharing a common Marxist approach. Carlo Aymonino’s Origin and Development of the Modern City developed from a talk given by the author to the symposium The Communists and the Great Cities organised by the Italian Communist Party in Milan in 1963 and is one of the first books that tries to create a platform of discussion about the premises for architects to operate in this new context. Aymonino, who together with Aldo Rossi is one of the key figures in the Italian architecture of the 1960s, aims to reply to another book published in that period by the architecture historian Leonardo Benevolo, The Origin of Modern Urbanism. The whole book, illustrated by Aymonino’s drawings and sketches, presents the history of the modern city from the industrial period to the present times in terms of the relationship between city and countryside, and between urban fabric and architectural reference points of the city, as he calls them. Sceptical towards the typical approach of urban planning, the zoning, Aymonino’s thesis points at examining the direct consequences of the various urban phenomena in the form of the city. This is where architects can apply their knowledge, intervene in this context and confront its problems. The book was one of the first steps of a very productive debate that included Aldo Rossi’s The Architecture of the City and many other researches carried out in the so-called School of Venice in those years.

On the other side, Leonardo Benevolo, urban planner and professor of architecture history, appeared in the Italian debate in 1960 with his thousand pages History of Modern Architecture. The book represented a crucial shift in the historiography of the modern movement since it was the first history of modern architecture based on a Marxist approach. According to Benevolo, modern architecture is not simply a matter of new formal values, like in the tradition of Nicholaus Pevsner’s, Sigfried Giedion’s or Bruno Zevi’s books, rather a problem of the relationship between society, economy and technique, all of them inevitably related to (and represented in) the physical transformation of the urban body. Therefore, if we want to reflect on the role of architecture in dealing with the city, we have to go back to the condition of the industrial period by marking the difference with what happened before.

For centuries architecture had the power to literally shape the landscape. Projects were products of an élite as clear representation of the idea of a specific client, a pope, a prince, a noble family, mediated by architects and translated into the language of architecture and urban planning. After the industrial revolution, this relationship collapsed and architects started to serve public institutions in order to face issues like the traffic jam and the generic speculative development produced in the city without the possibility of architectural control. Thus architecture became something different. More and more its discourse started implying a more general variety of issues such as the role of infrastructure in order to move goods and people across territories. In the cities the mutated social conditions of large strata of the population generated an overall rethinking of the role of architecture. At the same time modernization changed buildings from inside. With the development of the means of production, machines started changing the way architecture was conceived.

To show the crucial shift, Benevolo focuses on key projects of that period like the Crystal Palace by Joseph Paxton, an architecture that does not represent and cannot be compared with anything done before. The building was realized for the Great Exhibition of London of 1851, the first of the World’s Fairs, a project that in itself celebrated the dawn of a generic architecture that provides all the necessary conditions to host many different functions without using the traditional tools of the discipline. Or better, the building is a simple, repetitive structure that uses the tools of architecture, namely the structure, in the sense of renouncing to define itself in terms of space. All the representations of the Crystal Palace are mostly focused on what is inside the building, not on the building itself, which in fact disappears amongst the enormous amount of goods, products and life that happens inside.

The key figure that Benevolo presents as the real revolutionary of architecture is William Morris. Morris was a textile designer, novelist and social activist, at the same time producing ornaments and writing about a future world, like in his famous News from Nowhere, a socialist science fiction novel. This three hundred and sixty degrees figure is the emblem of a new role of the architect, technically skilled in a great variety of activity, while culturally and politically committed to imagine a new world. After Morris, architecture’s domain becomes inevitably wider. The quote that Benevolo uses often is taken from the famous speech delivered by Morris at the London Institution in 1880: “It is this union of the arts, mutually helpful and harmoniously subordinated one to another, which I have learned to think of as Architecture, and when I use the word tonight, that is what I shall mean by it and nothing narrower. A great subject truly, for it embraces the consideration of the whole external surroundings of the life of man; we cannot escape from it if we would so long as we are part of civilisation, for it means the moulding and altering to human needs of the very face of the earth itself, except in the outermost desert.”

In the early ‘60s, when Benevolo had just published his History of Modern Architecture and was writing The Origin of Modern Urbanism, he was teaching history of architecture in the University of Florence. Among the students who attended his lessons were Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, later founders of Superstudio, together with Andrea Branzi, Gilberto Corretti, Paolo Deganello and Massimo Morozzi future members of Archizoom. In Benevolo’s lessons, enthusiastically attended, they perceived a change of paradigm in the history of architecture able to explain the conditions of the present.

Radicalizing William Morris’ approach, Superstudio and Archizoom started working in a very dense relationship between thought, writing and image. Suspended between art, literature, science and philosophy, in their conception, architecture became the protagonist of a tale that systematically exceeded the description of its technical features, presenting itself as a way to read reality and react to its stimuli: “The myths of society take shape in the images that society generates. New objects are things and images of things at the same time.” The manifesto of Superarchitettura, the self-organized exhibition that signed Superstudio’s and Archizoom’s debut in 1966, is a statement of intent as well as a clear-headed analysis of the context in which the architect has to work. While official Modernism was fading away and the mythologies of the everyday, listed by Roland Barthes, triumphed, the manifesto of these Florence-based youngsters recalled the very beginning of Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, in which the French philosopher paraphrased the first lines of Capital by Marx: “In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.” Life, society, modernity, production, accumulation and most of all representation are the questions put into play, from which a new approach to the work of the architect should rise, primarily through a shameless critique of his main working tool, the design.

Working in a wide spectrum of activities, the two groups started looking at architecture not as the solution, but rather as the problem. As a conceptual context for their project they chose exactly what Morris had called the desert. For them the desert acted as a counterpart, as the fictional scene for the beginning of a new story. Especially for Superstudio the desert is the representation of the modern city in which traditional values are collapsing in architecture as far as in other disciplines. At the same time the desert is the representation of the freedom of movement from the traditional goals of architecture, opening the role of architects to a realm of activity completely changed and larger than in the past. In the photomontage titled To Furnish the Deserts, Superstudio critically shows that the problem is not to design the world, but to understand in which ways we can inhabit it.

![]()

fig. 1

To Furnish the Deserts

Superstudio 1969

The universe of small-scale objects, in those years, is in fact the driving force and the symbol of the Italian economic boom. Indeed, millions of rooms built in the two decades following the end of the war were to be filled, a boundless private territory, ready to be furnished and inhabited. However, according to Superstudio, the race for a useful design is a losing battle: “modern furniture seems like a great race towards the most beautiful, the newest, the most efficient. Nonetheless, being the first or the last to arrive is irrelevant, if the race is wrong. So, what should be done, rather than taking part in the race, is leaving it as soon as possible, isolating yourself in a corner to slowly pick up the pieces of your existence and use them to shape the tools you need for survival, to meet actual needs.”

However, by stating that: “poetry is what makes home-living.” Superstudio does not merely evoke the liberating potential of pop shapes and materials; rather, it uncovers the shape in which the real added value of objects hides, taking its logic to the extreme consequences. In the consumer society, the real traded commodity is exactly what exceeds the mere function. The real product is therefore the image of the object, with the double meaning of what it—actually and metaphorically—represents and of how it represents it (its shape): it is its rhetorical image. This is why they start with a series of provocations using strong representational tools. Images like those of The Continuous Monument were, literally, the representation of this problem, the demonstratio per absurdum of the consequences of the processes of modernization in which architecture is inevitably embedded.

![]()

fig. 2

New New York

The Continuous Monument Series

Superstudio 1969

While the neo avant-garde like the English Archigram, were exploring how to push forward design (almost until its dissolution) using all the technological and mechanical tools, Archizoom and Superstudio pushed the idea of reducing design to concentrate on the conceptual role of architecture itself. For Archizoom architecture cannot be analysed other than in relation to the city. For them the city is a machine, a productive device as a way of generating a project in which everybody collaborates almost automatically. Their No–Stop City, is based on the idea of work as the essence of living and inhabiting the city. The city, instead of being fully designed, presents itself as a banal mechanism, provocatively drawn using a typewriting machine. They said: “there no longer exists any reality outside the system itself.” Continuing: “so while once the system was represented by the city, today the city no longer represents the system: it is the system itself.” Therefore the No–Stop City has nothing imaginary about it. It is a work of inquiry into architecture and the city; a theoretical work precisely in the degree to which it is offered as a hypothetical and simplified scientific model; useful, as was Bohr’s model of the atom to modern physics. No–Stop City is a city that chooses its own logic as an artificial construct, wholly for use, independent of any nature outside and invisible. It annuls every picturesque dimension that still constitutes the essence of the modern city and its use, the promenade, and becomes a pure assembly line of society. Its references, the factory and the supermarket, generate an abstract, neutral, repetitive architecture which displays the functioning of the society as an urban machine, but one devoid of all iconographic references to the machine world, with the sole, relevant exception of those elements that relate to the structural and quantitative character of the city: the grid of pylons, the vertical subdivision into planes, the rhythm of the partition that articulate the continuous plane of housing. This continuous plan is the place in which dwelling, by embodying and rendering indistinguishable the condition of production and consumption, is transformed into the use of architecture in its pure state. The city, which has entirely absorbed every category of architecture, from the monument to interior design, becomes the empty space par excellence, available to any form of appropriation, a fully equipped parking lot, a machine for living in, in the most radical sense of the term, where production and consumption are the two faces of the same coin, that of the whole society put to work.

In this, Archizoom’s No–Stop City reflected the political thesis of the philosopher and theorist of the Operaist movement Mario Tronti. In the chapter ‘Factory and Society’ of the seminal book Workers and Capital, Tronti states that nowadays the whole society is de facto a factory, since the primary goal of capital is the reproduction of labour-power. Therefore production is inevitably extended to the whole set of social relations, affecting all aspects of life. As Pier Vittorio Aureli noticed in his The Project of Autonomy, Archizoom’s No–Stop City was very close to the work of the Operaist militant Claudio Greppi, who in 1965 had presented his diploma project in architecture at the University of Florence deeply rooted in Tronti’s thesis. The project was an urban intervention for a vast region between Firenze and the city of Prato that criticized the polarity between centre and periphery, proposing a model in which production and accumulation coincided in an isotropic plan finally liberated from bourgeois ideological representations of the city. Assuming the logic of the assembly line in a more radical way, No–Stop City hypothesises an indifferent architecture, endowed with enormous degrees of freedom of use and inhabitability. Thinking that the new architecture should be born not from a renewed language but a new use of architecture itself, Archizoom reactivated a fundamental theoretical dimension of modernity, the reduction of architecture to its essential dimension, which goes beyond the idea of language as style and arrives at the idea of language as structure, basically the essence of an architectural project. When we spoke of the death of architecture, recalled Branzi some years later: “a lot of people understood the idea as a return to living in caves and primitive culture. In reality we were drawing on an important strand in modern movement: Hannes Mayer spoke of: “an architecture that is no more architecture, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe of a city without qualities, Le Corbusier himself of a machine for living in. The reduction of architecture is part of the thinking of modern architecture.”

To conclude, to whom are these discourses addressed? Thinking to modernity it’s worth recalling the famous dedication of Le Corbusier, to authority in the book The Radiant City. For Le Corbusier the authorities are not simply politicians and technocrats, but rather everybody who is in the position and responsibility of taking a decision. Among these persons are architects. As architects we cannot design anything if we don’t design ourselves first, so to say. All these discussions are interesting exactly because they are directed to architects themselves. It is here that the notion of project opens a discussion about the role of education and the pedagogical function of architecture.

MT

The goal of the work of architecture cannot be understood solely as the making of a building or as an attempt to define space. Since architecture always concerns the making of something in a certain place, the goal of the work of architecture should always be the possibility of contributing to the transformation of a certain place or condition, being this rural or urban, social or political. While some architects have made the contribution to a given place, location or condition an explicit facet of their work; for others, on the contrary, this contribution remains of an unspoken character that can be fully understood only by carefully looking back at their work retrospectively. The ambition of architecture to contribute to a place or condition is something that implies the existence of what I propose to call architecture’s pedagogical dimension, namely the capacity of a project, built or unbuilt, to educate on certain tenets that concern the definition, transformation or even erasure of a given condition. Space, not differently from words, can function as a medium through which tenets, rules or principles are communicated. It can even be argued that spatial experiences are probably more effective and powerful than written rules or voiced lessons, since space and its qualities are understood instinctively through the very experience that each of us makes of them. In this respect, I would like to emphasize that the reference to the term ‘pedagogy’ here does not refer to the nexus between the work of the architect within the space of the office and the one within the space of the classroom, which would perhaps be the most direct relation between the professional and the educational dimension of architecture. What I am interested in discussing here is the pedagogical dimension that is to be inherently found within those architectural projects that aim at having an impact on a larger scale, namely a condition that exceeds, in physical or conceptual terms, the scale proper of the architectural intervention. If we look at architects from the past, the existence of such a pedagogical dimension or ambition was certainly more evident than it is today, and in many cases it was a rather explicit one.

The architectural treatise tradition, from the Italian Renaissance to the French Enlightenment, represents a clear example of such an approach. Italian architects from the 15th and 16th centuries such as Leon Battista Alberti and Sebastiano Serlio were as much concerned with buildings as much as they were with developing projects in the form of drawing and writing with the goal of educating not primarily young builders and apprentices, but those responsible for the construction of the city or the making of society. In these architectural treatises, it is crucial to recognize the capacity of architecture for becoming the tool through which ideas, policies, ideologies about the world could be brought forward. The work of Alberti and Serlio is therefore characterized by a tension between an ideal form, the description of which is contained in their respective treatise, and its concrete application. The co-existence of these two scopes substantiates the activity of building since this would otherwise be deprived of the framework through which this can be fully understood.

The modern movement was similarly characterized by the same understanding of the work of architecture as building and as pedagogy. Le Corbusier’s La Ville Radieuse was the attempt to summarize in one single proposal the rules at the foundation of his idea of the city. Between 1929 and 1934, Le Corbusier’s production focuses primarily on urbanism. In those five years, the architect developed a series of urban projects in which it is possible to retrieve the ideas, sort of architectural obsessions that characterizes his continuous reasoning on the city. The projects developed in those years are collected in the second volume of his Œuvre Compléte published in 1934, and in a book completely dedicated to urbanism and the project of the city, titled La ville radieuse. In this book the drawings of the project La ville radieuse, developed between 1929 and 1930, represents a ‘formal conceptualisation’ of the thoughts previously developed in occasion of the urban projects for Paris, for the cities of South America, for Alger, Geneva, Antwerp, Moscow, Stockholm, Rome, Barcelona and Nemours, which are presented here as a corollary of the rather abstract and site-less proposal of La ville radieuse. In this project are condensed and exemplified those principles that can be considered at the base of his understanding of the city, ideas and principles that will be repeated, re-proposed, modified during his whole life and towards which he felt a sort of pathological attachment, making of them architectural obsessions such as; a city constructed on different levels that do not interfere with each other; a green ground surface that runs uninterruptedly below the entire city’s surface; on top, the level of vehicular circulation; and on a separate level, the residential functions that are to be organized in the form of residential redents. The project reveals how each inhabitant has the entire surface of the city at his own disposal: the green ground surface is a large urban park within which the pedestrian will never have the chance to come across a car. All this is communicated through a few drawings, in which architecture is at the same time abstract and yet concrete, impalpable as a set of written guidelines and yet as tangible as an object.

In a similar way to Le Corbusier’s pedagogical ambition, Lucio Costa’s proposal for the Plano Piloto of Brasilia represents another relevant case of explicit pedagogy. Confronted with the task of designing the new capital city of Brazil, Costa developed a proposal that was primarily communicated through a text, the famous competition report, and a few sketches that accompany the text of the report as well as a plan drawing. Especially the report contains a clear description of the principles through which the city was to be built. Rather than a detailed and rigid urban masterplan, Costa understood that the task of designing an entire new city was primarily about the definition of a limited number of architectural principles that would allow for other architects to be able to work within the framework originally defined by the architect. Costa’s idea of the new capital city can be summarized on the intersection of two main axis, the monumental and the residential; in the form of a cross, the invention of the superquadra to tackle the residential problem of the city (along the so called residential axis), a new idea of monumentality derived from the relationship between simple architectural volumes (the political and administrative institutions of the new city) and the articulation of the ground (along the monumental axis), the relationship between built and un-built masses, intended as the relationship between architecture as building and as vegetation. These principles and ideas became the framework upon which numerous other architects, builders, engineers, and entrepreneurs came to Brasilia to work on the construction of the new capital city reinterpreting, sometimes improving, sometimes, unfortunately, hindering Costa’s original urban lesson. While these cases exemplify what I consider as explicit pedagogical projects, there are also cases in which the pedagogical dimension remains rather an implicit facet. These are projects that have proved to have had the capacity (and in certain cases the luck) to become lessons and to offer a contribution towards the making of a larger condition. A few examples come to mind.

The invention of the urban typology of the courtyard building (the Hof) in Vienna during the social democratic local government not only completely altered the idea of the city of the 19th Century made of perimeter blocks and became a model for the multiple public housing interventions that were built between 1918 and 1932, but also concretely contributed to redefining the political condition of the city. The large courtyards became containers of public facilities to be shared by the inhabitants, so that the form became the perfect embodiment of a new idea of society.

In his thirty-year long work at Monte Carasso in Ticino, Luigi Snozzi has gradually won acceptance from the villagers. Originally invited to work on the new village’s masterplan, his building by building planning method together with a few initial interventions became involuntary models not only on new planning rules but also on what the architecture of the village was to become. Slowly, the visible signs of Snozzi’s abstract, minimalist vocabulary have been gradually taken up by other architects who came to work in the same village, eventually creating a series of buildings in which the ones built by the disciples are indistinguishable from those of the master.

Whether explicit or implicit, pedagogical projects are today hard to encounter. On the one hand, the work of architecture is more and more recognized as the production of buildings as singularities, the goal of which is strictly confined within the production of the object itself. On the other hand, large-scale projects are mostly translated into the production of rigid masterplans that are nothing else than dimensionally ‘exploded’ architectural interventions. Contrary to these trends, in our work we have been very much interested in the redefinition of large-scale design, or in ways of tackling the project of the city from the vantage point of architecture. A series of projects for different cities or urban conditions, developed mainly during the last decade, have become the occasion to reformulate both the possibility of a pedagogical dimension of the architectural project and concrete attempts to overcome the inevitable impasse that is related to the architectural intervention at the large scale.

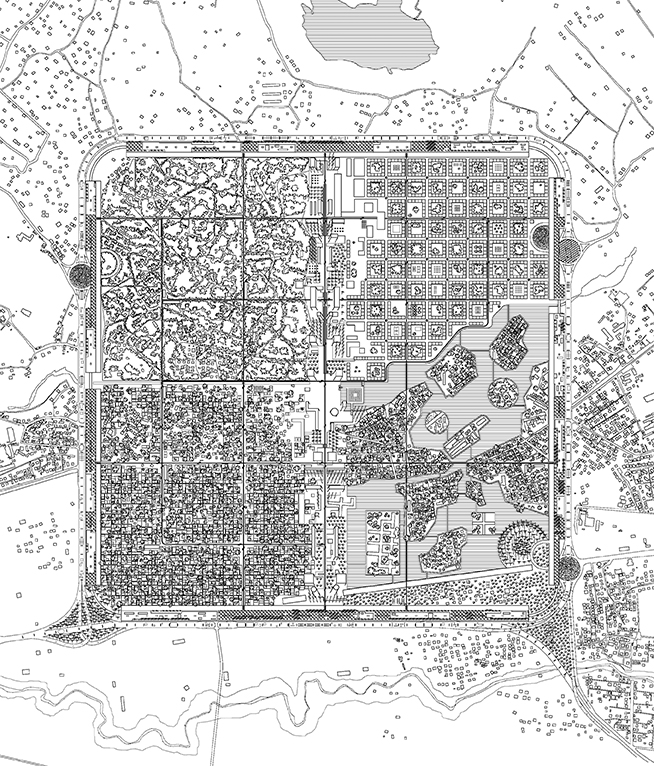

Developed between 2004 and 2006, Parallel Tirana was a proposal that tried to address the newly acquired territorial dimension of the capital of Albania. For decades a typical medium-sized city, following the fall of the communist regime that ruled the country for most of the second half of the 20th century, the city started to attract citizens from the country’s south and north and from the neighbouring Kosovo. The strong and fast process of urbanization that resulted from this migratory process took place without any plan. Thousands of new houses were built outside what were considered the traditional borders of the city, especially in the northwest direction, invading what was until that time a fertile agricultural plain expanding towards the city’s airport. Parallel Tirana attempted at offering a solution to this condition through its gradual transformation rather than through erasure or the simple process of legalization of the status quo that was by many advocated. Starting by reading the spatial conditions of the old city centre and its qualities, four main urban spatial typologies were identified. These were translated into four different tools, each to be used to intervene on different parts of this forming urbanization. By applying these spatial models to four distinct parts of the territory a new parallel city was defined, born out of a somewhat illegal and informal settlement but that soon became a sort of mirror of the traditional city. Each of the four parts of Parallel Tirana was at the same time a concrete proposal in a specific place of the city and a series of recommendations for the future transformation of an informal settlement into something that could still be recognized as city.

![]()

fig. 3

Parallel Tirana plan

Albania 2006

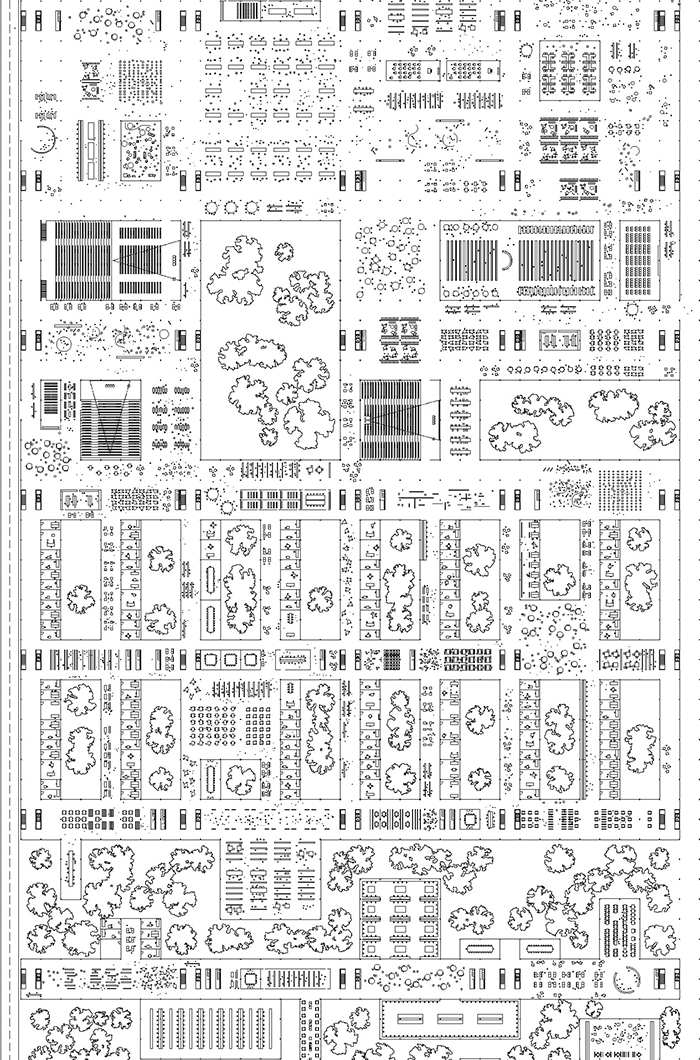

The project Gardens, Fields and Workshops for the new Osong Bio-tech Valley was a large-scale project developed within the framework of an international competition concerning a new town to be implemented on a site of 1.1 million square metres. The program was extremely complex and it included research and development facilities in the field of bio-technology, such as a research centre for new medicine and a support centre for the development of medical equipment, and the new town was expected to host ten universities and a large university hospital. Given such an unprecedented concentration of large-scale knowledge institutions, we understood that it would have been impossible to entirely control such development. The goal of our proposal was to set up a series of basic urban rules through which the city could be built in phases, over the next years or decades, accommodating those transformations that would follow the original idea, without ever losing its original logic. The project was based on an incremental structure made of parallel linear strips of built and unbuilt space. Each strip of built space is made of buildings that frame gardens in between. At the scale of the town the principle of alternate strips guarantees a limit to urbanization and the possibility of constant proximity of open space, while at the scale of the strip it allows an infinite range of possibilities to develop in the space between buildings, which can consist of hills, agricultural land and farms. Unbuilt strips are made of fields where crops that relate to the bio-technology industry can be cultivated. Rather than in a piecemeal fashion, open space runs through the city and becomes its very structure. Gardens in between buildings function as belvedere open towards the agricultural fields. Rather than being just a backyard space, or a decorative complement to buildings, gardens become an integral part of urban development.

![]()

fig. 4

Osong Bio-tech Valley visual

South Korea 2011

While agricultural fields and gardens constitute the fixed background of the city, the architecture is flexible, generic, and even rough. The flexibility of the ground floors allows exchange and permeability between different buildings. Instead of developing buildings as distinct entities, they are arranged as part of a continuous pattern even if they may be owned by different institutions and companies.

![]()

fig. 5

Osong Bio-tech Valley plan

South Korea 2011

In our proposal the anonymity of the architecture and its emphasis on the field condition of the campus is meant to reinforce the sense of collectiveness while rendering in the most objective conditions the productive reality of the new town.

The two projects that I’ve described exemplify different ways in which architecture becomes pedagogic, contributing to the definition of a larger scale, and aiming at the transformation of the urban or rural conditions, through the communication of central rules or principles. Through our work, we aim to bring back and revive the explicit and now perhaps even forgotten tradition of the pedagogical dimension and ambition of the work of architecture.

PL

There is so much to talk about here. I have a basic and naïve question for the two of you, though. What is the relationship between the two presentations?

MT

I think it’s an understanding of an architectural approach to the city which, despite the different epochs we have talked about, is to understand architecture as not only about craft and how buildings look, but also about the process behind the construction, in our case the construction of the city but also the construction of any other part of the land and territory that could be part of an architecture project. So in a broad sense that is what brings us together with the work of Italy of the 1960s and our work today.

GM

I have a definition that I missed in my presentation. It is the idea that architecture is a device, in the sense that Foucault used the word, a despositif, something that can enhance and maintain the exercise of power within the social body and once we realise this rule of architecture, of the work of architecture and the city itself as a device, immediately our role as designers, change. It changes radically because it is not about finding the best form for a program, but to being responsible for the implications of our act as architects, once we imagine a certain kind of space. The second term I think is important is the idea that architecture is a system and all the projects Martino showed, to me, represent how Dogma are interested in the idea of architecture as a process that starts from a specific form and gesture that implies a specific form. I think both the Superstudio and Archizoom projects put the issue in what they call ‘demonstration-absolut’, the destiny of architecture to provide visions. This shows architecture is always intended as a system, so architecture can be a network, a continuous building, a single object, something that activates the process.

PL

The fact you see a relationship between the work of Dogma and the work undertaken in the 1960s is interesting. In Dogma’s work there is an aspiration to say the place of the architect is to help us to conceptually think about the city and that way of thinking is at odds with our contemporary culture. Are Dogma drawing on an intellectual resource whose time has gone by? You were talking about the place of the architect changing as a result of mechanization, then again because of the post-Ford shift. Are you saying it is possible to reclaim territory through their work? Or what relationship do you see from the past and present, because today people often reduce architecture to the craft of something, not even to design.

MT

Our experience has shown there is an interest in getting more concrete in relation to the transformation of the city and to overcome an impasse in current contemporary understandings of architecture. There is a necessity to go beyond contemporary understandings and practices of architecture put by architects, politicians and authorities so I hope being interested in that field there is a possibility to do so.

PL

Are there any questions from the audience?

AUDIENCE

Yes, I am interested in the relationship between architecture and infrastructure. Are you trying to reconcile that relation?

MT

I don’t think there is a direct interest in infrastructure per–se. On one hand we have a growing scale of the city, which is also a cause of the impasse we witness today, and also because of the enormous infrastructure work present in the city. But on the other hand we are not interested in making megastructure architecture. We always want architecture to be defined by its specific limit. This is the idea of working with something very physical. But it is also very conceptual. We are looking for some kind of principle, and of testing a possibility that is not present today. There is a necessity to deal with infrastructure when dealing with the city though. We need to think about the form that can best accommodate possible alternatives to the current making of the city. There is a similar idea with the room in our ‘frames project’ as an attempt to make an alternative to the infrastructure approach, but through the extreme repetition of rooms.

AUDIENCE

What is the role of the architect in the large-scale competition project?

MT

We have been working on a competition for Brasilia. Everyone knows that city for the great architect Oscar Niemeyer but in fact the project of Brasilia, the urban concept, is by another architect called Lucio Costa. His project has the capacity to become either a metaproject or constitutional strategy on the basis of which the city has been built, but not by Costa or Niemeyer, by a series of architects who have been able to pick up the principle Costa originally put forward in his text for that city. It allowed the city to develop according to a unique conception. In a way the role of the architect, and at the time Costa didn’t have an office and only went to Brasilia a few times, he had a role that is very different to the current role architects have, but important in order to enter the scale of urbanism.

AUDIENCE

What kind of projects does the office work on? You show polemical projects. How do you live?

MT

We have our research projects that have sustained us, but of course we do other projects and teach because we need to survive, to eat! But nonetheless trying to put forward an idea that challenges the urban conditions. Right now we are doing several projects that deal with social housing, which has been interesting because of the collapse of the welfare state in Europe, the question of representing collectivity as a critique of the current condition. In a way there is a certain critical approach in our daily office practice to become a tool to answer emerging requests, like a normal client would have in our age, especially in the crisis in which we are living.

PL

So you are saying that a possibility can still exist in apparently much less ambitious projects? I’ll take a few more questions.

AUDIENCE

Can you say something about the importance of the ‘idea’ in your projects?

GM

Your question somehow implies it is just an idea, but ideas have a reality. Our presentations shared the view that ideas count. Ideas are the reality. It is what Martino was saying earlier. To try and realise how, as intellectual architects, to frame our activities, we produce the city by means of actions including ideas. Because ideas, in the form of drawings, you might say drawings are just drawings, but now we live within drawings, images, if you think of the internet and how our world is completely immersed in drawings, pictures and images. I know people who live in this dimension and they think this is the world, and I agree with them, but if this is the world then the role of our ideas when they are formalised in some way is much more crucial than what these ideas are anticipating in terms of the possible physical construction of what we can see in the world.

PL

You can also argue that ideas are important because they are what make us human, they are a universal fact.

AUDIENCE

I think it is interesting when you talk about News from Nowhere and the unrealisability of utopia. You talk about legibility and framework. In the past, these utopians had an idea of who this change would be for. I wonder if this is also at the heart of your proposal? I am talking more on the level of labour and people, the human dimension.

MT

Yes, it’s an important thing to say what you have said. In a way the idea of the subject and to whom we address our work is something that is present in our research, thought, and ideas.

GM

I’ll say just one thing. The word human can be tricky in the sense that if human is about the man, which is a concept invented at a certain moment and which Michel Foucault has written beautiful pages about. The invention of the concept of man is also the invention of the program. There is an idea of the individual, but at the same time it is also the beginning of an approach to things in which we are condemned to be alone because we are individuals who cannot share everything. The problem of modernity and the process of inventing tools becomes crucial because the starting point is that we are all individuals. I think as architects and as intellectuals we should question these things, but it is critical that if we take this question to an extreme point we have problems because we have to renounce the freedom that loneliness implies.

PL

Historically, these questions are associated with a strong sense of agency, collective agency in particular, so maybe there is the question: do you assume you have to revive that sense of agency or do we live in a world in which we are all individuals and the debilitating sense of being an individual is limited and therefore to suggest a possible future, demands a different attitude toward agency? The problem with that is what you project, you still need somebody to make that world and if it’s not Corb or the revolutionary movement of 1917, then it’s a bureaucracy because that’s all that’s left in a world. So what is left for the architect? The architect as a consultant who gives nice imaginative ideas to a bureaucracy? The key thing about urbanity is freedom and agency, isn’t it?

MT

It’s difficult to answer. Going back to the project you have seen from us. The scale from that condition does not belong to the realm of architecture. In a way the goal is to reveal something that is hidden, or latent, unnoticeable in the contemporary situation. Our work isn’t putting an ideological project but a pedagogical project that tries to help understanding of certain situations rather than simply proposing an alternative exit.

AUDIENCE

Is there a hierarchy in the crosses of your Walls project?

MT

We were not developing hierarchies of programme. The programme goes beyond the scope of the work. The only principle is what you see in the diagram and how the construction of the city would evolve: the proportions, the height of the building, framing the program. The project of the city goes beyond programme. You cannot design the city, it always goes beyond any attempt to design it. At the end we put forward clear and pragmatic principles or rules that would give a direction to development. There was no hierarchy but an idea of the program to then reveal the program of this city of administration. The rest would accommodate itself in the space produced by the forms.

GM

The proposals like Dogma’s see the process of dissolution of the traditional goal of disciplines including architecture and arts. Pier Vittorio’s lectures used to go through the many experiences of modernity in architecture and also in the field of arts, arriving often at the conclusion of the role of the discipline inevitably becomes, from a formal point of view, weaker and weaker, and that means also in a metaphoric point of view to move back. We are right now in a world in which it seems that the prophecy of Nietzsche is completely realised. The world is a huge work of art and everyone is an artist! Proposals like this counter and question if that is true or possible, or if it is useful that this is the situation.

PL

When you are trying to conceptualise contemporary urbanity there is a theme of the campus in contemporary architecture as an idealised form with a childlike quality where people don’t live out their lives in a rich way, but where everything is orchestrated.

MT

Within the transformation of production the idea of the campus is pervasive within the city.

GM

The separation of the campus is a problem. But we can also say that separation is also a possibility of engaging what is outside the campus and together with creating a subjectivity that is related to our condition of being separated. I think that there is also an idea of dispersion that does not imply a good thing, what I am sure of, is the concept of separation helps us to understand the condition in which we live. So the idea of the pedagogical aspect of architecture is here too. I think again we can see the project by Martino as not simply problem solving, of how to provide the necessary frame for a possible city, where we see only one side of the issue. We also see the necessity of an understanding of that condition of living in a contemporary city as a very realistic one.

PL

Instead of architecture being an isolated project in the city, your projects become a collection, inclusive and repeatable. Is that what your project is trying to achieve?

MT

Our approach is not just enlarging the scale to include more of the city. The crucial issue is of reconciling two scales: the city as metropolis and the city as architecture. Our project doesn’t aim to enlarge. It can be something that is also very small. It serves to underline and define something. Pedagogically, it makes something in the history of the city more relevant. Our project is both physical and conceptual. We don’t invent new forms; we repeat a few strict principles. The most recurring figure is the square, a certain scale, a critical mass, the limit, which can be a line. Often the aim is to avoid something.

AUDIENCE

I’d like to ask a question about the idea of the individual. Has the ‘me’ been hijacked? Now you have to understand the ‘we’ in your work, the way you are defining edges and borders for a ‘we’?

GM

What you are saying is a new notion of ‘we’ and to understand how there is a change in our urban condition. That is what we have seen in the projects today. Not in a primitive way, as in community, or by religion, but these projects are very realistic and deal with the actual conditions of the city to test what this new reality is, and what a new idea of collectivity can be. If we go deep into the conceptual premise of the projects we have seen, in the modern history, the slabs. The conceptual premise of the slab is very different. The idea of collectivity was totally defined, what happens in the slab and in the frame. We can arrive at a concept of the city and how to inhabit and live in the city which is very different from both the modern model and also the contemporary model.

PL

What about the programme? Although you said your project is not about programme, will there be a point when the programme comes back? The programme at one point in the history of architecture was a way of saying what kind of aspiration a society could have.

MT

In a sense the reason programme has not been on the agenda is because we come out of a history when programme has been too much on the agenda. Programme was technical and managerial. What has been completely neglected is the possibility of form, but that doesn’t mean the programme is irrelevant. The project is also a method to strategize. The project can streamline our work. Is it fundamental for the architect to be in control of the programme? Or can the architect be in control of something else?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()