CONTACT

Custom Lane,

1 Customs Wharf,

Edinburgh,

EH6 6AL, United Kingdom

mail@aefoundation.co.uk

DIRECTORS

Nicky Thomson

FOUNDING DIRECTORS

The AE Foundation was established in 2011 to provide an informed forum for an international community of practitioners, educators, students and graduates to discuss current themes in architecture and architectural education.

![]()

MIKE DAVIES

KESTER RATTENBURY

︎︎︎Penny Lewis

POMPIDOU

PL

The purpose of getting you all together here tonight is to discuss the optimism and energy that existed and gave rise to the Pompidou Centre, not only as a building, but also as a competition. Despite economic uncertainty, forty years ago a young practice with a radical design solution, generated a very unusual and stimulating piece of architecture, and to quote: “with a positive approach to design technology and innovative design solutions.” Perhaps it’s appropriate forty years on, to revisit that project and the inspiration behind it, the problems and difficulties, but also its legacy. We’ve invited two speakers to join us tonight. We have Mike Davies from the Richard Rogers Partnership, and who you might know from the colour of his clothes, and who worked on the Pompidou, and Kester Rattenbury, an architectural journalist, critic and writer, who will, through her work on SuperCrit, provide some critique and context for the Pompidou.

KR

I think it’s incredibly exciting to talk about this building because to me this is one of ‘the’ great buildings of the age, the absolute ‘can-do’ moment of technology and youth, and something that was actually built, which was completely extraordinary. But actually, and I’m sorry if this sounds like overkill, I think this is one of the great buildings of any age. It’s just one of those buildings that distils a moment in history but somehow changes it. It’s completely quintessential of its time but not compliant. So, it’s a great paradox, which I think is one of the things that makes it really great.

It was built immediately post May 68, and as a direct result of the street protests, which marked the effective end of the right wing government of Charles de Gaulle. It was commissioned by his successor who was also a right-winger but a more centrist right-winger, Pompidou. And it was meant to be a response to the streets. It was meant to be a response to this kind of mood. Or at least that’s the way the jury made it work because they did actually pick the building that did that. There were certainly a lot of competition entries that didn’t do that, that were completely straightforward and conventional buildings. So, on the one hand it’s a total triumph, a really new and unprecedented building, one we hadn’t seen before, and one where we really didn’t know what was going to happen, and many people do see it like this, as this great triumph. On the other hand you could see it as completely the opposite, as a kind of sop to the Left, a classic state institution in radical clothes, a sort of Trojan horse that managed to reinforce the state under the pretence of being more radical. And there were plenty of people who saw it like this, Cedric Price and Archigram for instance. There’s a great movie for any of you interested in looking at it. It’s by Denis Postle and it’s called ‘Beaubourg: Four Films’, and there’s this great tour by them sort of slightly damning it with faint praise, possibly a bit jealous, you know—laughs. But amongst the people who were critical and took this line of arguments was of course Richard Rogers, as Mike Davies already said, when Arup were trying to persuade the team to do the competition, he said: “Who the hell wants to do a centralised arts centre when everyone else is trying to de-centralise culture, and who on earth wants to do a monument to Georges Pompidou?” But he was persuaded of course. In a way it’s the classic architectural dilemma. Young radical architects always want to change things, but architecture is so inherently expensive, and so inherently dependent on power, that it’s almost inevitably a form of compromise. And this was really the building where this argument was played out live. The project that it was compared to most, generally it was compared to Archigram, but it was the Fun Palace by Cedric Price, that the Pompidou was the built version of the Fun Palace. Which isn’t quite true actually. The Fun Palace was a really polemical building, but was effectively designed to resist this process of institutionalisation, of the state taking over. It was designed not to be a building at all, but be a kind of amenity, a sort of stage set, which was for people to use and resisted in everything that it did, the capacity to become a state building. One of the things that Cedric Price did deliberately was to make sure that the technology was never glamorous. The idea was that you shouldn’t ever like the building so much that you would want to keep the building once its function changed. He thought that architecture should provoke you to change and that in order to do that it shouldn’t be so glamorous. This is one of the dilemmas that was played out here, and when Reyner Banham, the great critic of the age, said about the Pompidou Centre when it was built: “How can you have a monument to change, it’s not possible, and yet somehow it kind of works, it is a monument to change,” he said when it was built. “I don’t really understand it.” But he called it “the enigma of the Rue Durenard—a miracle.” It was both a monument and something that symbolised change. The Pompidou was different, it was part of that era with Cedric Price, Archigram and all those great projects that were trying to resist institutionalisation, but it also related to a lot of other things as well. Richard Rogers quotes the Eames House as being a much more direct reference, which of course is much smaller, and the scale of buildings that Richard and Renzo had been making up until then were much smaller and domestic, but also very makerly, very simple, very direct. There’s also the side of things that Mike was looking at in the west coast of America with Allan Stanton, and Chris Dawson also on the team in Chrysalis, which did an amazing range of pop-ups, vehicles, buildings, machines, all kinds of things that weren’t really architecture, but which were built, and they were built for a whole range of clients including commercial clients, which is again a slightly different take from the idea of the time. But they were built and that was part of the way that the Pompidou Centre was different.

The technology was not like Cedric Price technology. It had to be glamorous. It had to seduce the politicians into backing it, even after Pompidou had died. It was a big building, a cultural institution, in the centre of one of the most historic, and in a way, old-fashioned cities in the world. So, it had to tread this difficult line between an expressive technology and something that was buildable, and in fact another Renzo Piano quote was that he called it ‘a parody of technology’. The technology in a way became over expressive, became a way of making the argument more visible, even than it needed to be. That’s kind of important. It can stop you noticing what the building’s doing, so those gerberettes get photographed all the time, but what they’re for is actually to create this enormous fifty metre clear-span space, and to keep the flank walls as transparent as possible, so that there wasn’t a break between the building and the piazza, so that it would be one continuous space, that’s much harder to photograph than a gerberette. Other things like that, the escalators, seem to be this wonderful moving sculpture in the square, and indeed they seem to have been liberated from shopping malls or offices where we’d seen them before, and suddenly move into the public realm. But what they’re really for, as Mike’s also mentioned, was to provide this great free ride over Paris: this amazing view far better than the Eiffel Tower, a much better view—and free. And I think that all the photographs of the building show you very important things about the building, which is that it’s not so important as an object, but that it’s more important to look at the way it’s made and the way that it’s used, because the way it’s used is really fundamental. One of the fundamental things about the way it’s used isn’t technological at all, which is the piazza. In fact the piazza is very intriguing because it’s kind of really traditional urbanism, and seems to be the opposite of the Cedric Price/Archigram kind of way of setting things out. Mike’s already mentioned that it was unusual because unlike all the other competition entries, or almost all of them, it moved the building up to the site, reinforced the street line and opened up this new square, which cut in to the red-light district and gave this complete explosion of life, which the building needed. But it was based on the Campo in Siena; it was based on a traditional, almost what would become a New Urbanist way of looking at the city, an old-fashioned way of looking at the city. Later on, this became a key part of Rogers’ urbanism, and I think some people see that as having come later, this sort of mixture of dense urbanism, fairly traditional urban forms, and technology, and culture. But in fact they were all there from the start, the offset of the square with the new technology was incredibly important.

The radicals like David Greene and Archigram say that the building should have been knocked down long ago to fulfil its promise that if it had really worked, it wouldn’t have been there at all; its not just that the floors were still moving, but that it should have gone off to Belleville long ago and tried to revamp that area. And to some extent those arguments about buildings institutionalising things have kind of been proved right, because the kind of changes that have so far been made to the building certainly have made it more conventional. Buildings do tend to institutionalise things, or people do use them to institutionalise things. So, in the 2000 revamp all kinds of really key things started to change; the escalators most importantly, as I’m sure some of you know, which used to be this great free ride for everybody are now only accessible on the most expensive ticket you can buy. So, that idea that the escalators were part of the public realm has gone. And it does feel a little like you’ve been disenfranchised when you go there. In order to make this change they had to alter a lot of things, they had to put a whole new lift system in to get you up to the library, because libraries in France are free by law. They had to do an awful lot of work to make sure people couldn’t use the escalators. There’s lots of other little things like that, the foyer is getting more and more closed in, you have to check in, you have to have your bags checked, you have to get rid of your baby buggies, you know, it’s really complicated to get into the building, and there are fewer bits you can get to. I think the café and the bookshop is just about it. You shouldn’t really be able to see those changes, because they’re not really visible changes, but I think you can. I think you can smell those ticket prices. I had a big attack of false memory syndrome after the first time I went to visit the building after the 2000 revamp. I went and looked at it and thought: “Oh my god they’ve painted it all white, but it’s always been white.” And I was absolutely convinced that they’d changed this thing, and that Renzo Piano had done it, that he’d got his revenge on this parody of technology to make it look as much like an office building as he possibly could. But actually when you look at the photo’s, it’s always been white, it just seems different somehow. Richard Rogers, at Supercrit, said that it’s to do with the square, that because there’s public space all over Paris now, that there’s no longer this ‘one’ square where you explode into public life. But they’ve also tidied up the Atelier Brancusi, so it just doesn’t have that rough-edged feel anymore, it does feel smarter, and you know, kind of more corporate than it used to. So, there is a case for the argument of the building tending to institutionalise things. But at the same time, there’s also the argument, which is made very strongly by the team, that the building is capable of change, and of changing back really easily.

To some extent this building has been a victim of its own success. At our Supercrit we had David Greene on the panel and Richard Rogers doing a presentation, and David Greene took the idea of the crit really seriously, and he gave Richard quite a rough crit actually. He told him it was stupid to put the pipes on the outside, that was obviously a bit of a joke, but then he said that the building should have been demolished long ago, and he definitely meant it. Then he started talking about commercial work and said: “Your early work was really brilliant, but you’ve really gone off the boil since then.” There were absolute gasps of astonishment and horror, and Richard very generously explained the other point of view, I don’t know if anybody was listening, but he put it very clearly and well. He talked about the difference between imagineers like David, who were pushing the bounds of what you can think about, and architects who build things, who change things in the real world, the people they have to persuade are the clients and the politicians, and that there are sometimes very incremental changes that you can make. You can do it in commercial buildings, just a bit maybe. And indeed I think you could say that another of Rogers’ great projects is, and it’s a really big one, to make the whole commercial realm that bit better, that bit greener, that bit more designed and more civic with more public space, and to shift the norm so that office buildings do have a greater civic responsibility than they might have done all these years ago. But the Pompidou was probably the building that took the biggest step in the beginning, and this was not a small step, it made big changes in the liberalisation of the city, of museums, of public space, and in the realm of what we thought was possible to do as an architect. It has become a bit institutionalised, but maybe some if its problems are what make it great, because it reminds me of the mosque in Cordoba, which sounds a bit like a stupid comparison, but that’s an incredibly problematical building, but incredibly brilliant at the same time; this vast shed made of columns that were scavenged from Roman and Greek and Christian buildings and made into the biggest mosque in Europe, and then taken over and reclaimed with a Renaissance cathedral, and Spanish Muslims are trying again to get permission to pray in it, which has been consistently refused, a very problematic building, but absolutely brilliant, and one that speaks huge volumes about the culture that made it. To me the Pompidou does something of the same for our age. So, to that extent I disagree profoundly with David Greene, because I don’t think it should be knocked down. Because even if it became completely ossified, it became complete archaeology, it would still be expressing something about cities and culture and about the possibility of change, and in any case we can always just hope that it might get changed back again.

MD

Some thoughts on the Pompidou. We were accused of taking down the Baltard pavilions at Les Halles, which was of course absolutely inevitable, because we were foreign, and the French at that time were extraordinarily chauvinistic. The idea of foreigners doing a building in France is almost unheard of, certainly a building at the sort of scale we were looking at. So, we were inevitably, immediately accused of taking down the Les Halles pavilions, with which we had nothing to do whatsoever. In fact, our site was the car park next to Rue Quincampoix, which was in fact one of the great prostitution streets in Paris. Our site had lot’s of diversity and interest: car park, prostitution, pigeons, rats and so on, and it had been a car park for many years, in fact ever since the war. It was an interesting site, bang in the heart of town. The architecture alongside, the Rue du Renard, Rue Quincampoix and the Rue Saint-Martins was this wonderful mix of very similar, although individually diverse buildings, all with the maximum height of twenty-eight metres, which we didn’t realise was significant until later on, is in fact the maximum height you can walk up before your heart gives out—laughs. And the maximum height a fireman’s ladder will reach in France, which disciplined the project to a significant degree.

There was a big international competition, the biggest international competition ever I believe. Six hundred and eighty two or three entries, an open competition, and our practice never went in for open competitions because it’s just such a bun fight. But at that time Arup’s persuaded Richard and Renzo, who were a practice of the huge amount of three people at the time: Richard, Renzo and one young assistant called Andrew Holmes, and that was the practice, and in the Arup’s said: “come on, this looks like an interesting project,” their arms were twisted and the story is Richard didn’t want to do it, but was eventually persuaded, but as he said: “thank god they persuaded me.” And it was a huge competition. The brief was for an arts centre, a national library, but nothing in the brief implied, really, what we were getting in to. Nobody said this was going to be a national monument, nobody said it was going to be a national piece; it was just another building project. But the make-up of the jury should have told us that things were going to be different. The jury was quite extraordinarily unique, Jean Prouvé, who we much admired, was a great French engineer, admired by the architectural profession in France, as the man who used to be able to do things, as opposed to draw things, there was a huge rift in French architecture at that time, between the Beaux Arts, where artists drew buildings, and then you called a bureau d’études, to work out how to build it, to design and detail it, the size of the radiators and so on. There was a huge gap between the artist and the scientist. Jean Prouvé was the great bridge between engineering and the architectural profession in France. Philip Johnson needed no introduction, a real American architectural showman, and he was a showman to his dying day and certainly was on the jury for the Pompidou. Then there was Oscar Niemeyer who’s 103 (2011), still around and still practicing, which is absolutely wonderful. It was a competition and they literally cut there way down from six hundred and something entries, to thirty-six, and then from thirty-six remarkably, to one, and they all said, this one! And everybody was a bit stunned because it was radical. It was only one of two or three entries that didn’t cover the whole site, and the key point of our building is that it didn’t cover the whole site. There was a wonderful egg that also didn’t cover the whole site, an egg with scales on it that was a couple of hundred metres high, it was unlikely to win in central Paris, but a remarkable number of the other projects basically filled the site to twenty-eight metres, plus one floor, which is in fact the level which was in fact the level of the great map of Paris, the plane of the roofs carries on at. In short, they chose us, which was quite extraordinary. Richard was immediately called to Paris. They said: “There’s going to be a river boat party.” And he said: “Great!” and they all got their ‘Screw Castro’ t-shirts on and their jeans, and went off to Paris in a Citroën Méhari, on the Ferry, and they arrived in Paris in their party gear to this line of French officials, all in dinner jackets, and thought: “oh my god, we’ve misconstrued what this means.” And Robert Bordaz, who was then already the head of the client body, had the aplomb, and Ruthi was there, and he hugged Ruthi, and she hugged him back and broke up all the tension, and it was a wonderful party. But that was one of the problems with France; the formal French versus the informal Brits was quite a challenge for a while.

The design concept for the building was about openness, about accessibility, and what was in many ways about the liberalisation of what was a great institution, which was the arts gallery, the basilican art gallery of the ‘50s and the ‘60s, and the library, of which you had to be a member, with two letters of recommendation, and around which you walked in discreet silence, were being challenged. The idea of the art gallery being more open, the library being a more accessible place, were parts of the concept, and also the whole idea of information. I was at the Architectural Association when a friend of mine, Chris Abel ran into the room, with a photograph from the states, and it was a Lincoln Continental, with the doors open and on the back of the driver’s seat there was this huge black box, about the size of a suitcase, and on the top of it was a telephone, and he said: “my god, this is a mobile phone!”—laughs. It was unbelievable, a complete eye-opener, we looked at each other, and things dawned, what would happen if the idea of communication was not fixed down, and of course that was the beginning of the information revolution for us as students at the AA. But you’ve got to remember the context of the time, the context of the time was people going to the Moon, it was a highly technologically optimistic generation. Archigram were drawing technologically virtuoso projects, NASA were putting people into space, and there was a lot of very successful technological advance at the time, electronics was just beginning to get into its stride, well pre computing, but there was a sort of optimistic feel to the whole generation and we were also challenging the establishment, and concerned about the notion of alternative energy and the idea of ecology. I first came across the word at the AA in a book called Dune, where what happened on one side of the planet might affect the other side, it was quite a remarkable idea, almost unheard of, which began to seep in to the thinking at the AA. Then if you went to the American mid-west you saw windmills and campfires and people living autonomously, and there were some messages there, there we were in cramped Europe, in big European cities, and of course the States was offering the opposite extremes, Los Angeles, the city of the car and the country of the great open space, which we all wanted to visit as students.

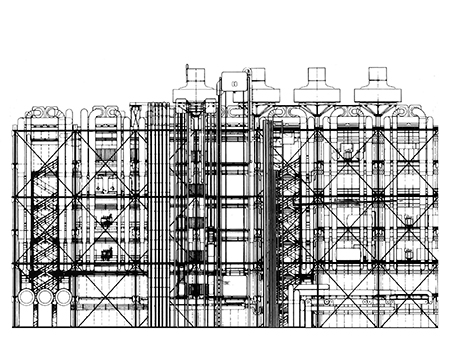

The building was about openness and I quote: “A live centre of information covering Paris and beyond, and locally as a place for people to meet.” And that really was what it was, and it is that today in many ways. The concept you already know, the radical proposal was to build to twice the height on half the site, which left half the site as open public space. One thing that was striking about architecture in the ‘60s was that there was very little acknowledgement of public space and the role of public space. There was the private, a site boundary and the pavements, and the idea of an interstitial space between the private and the public was relatively poorly developed at the time, and we were trying to blur the boundaries. It was very much to do with blurring all sorts of intellectual, creative and physical boundaries in the city, and the project captures this in many ways by giving over half the site to the public as a piece of public space, with a very strong, very clear, not very local building on one side of the site, one hundred and seventy metres long, and the rest as an open place. This is probably the most iconic drawing of the building, inasmuch as it captures the spirit of it. It was essentially a framework, and on the outside of that framework it wore its heart on its sleeve.

![]()

fig. 1

Centre Georges Pompidou Elevation

Paris 1971

It was a place where what was happening inside could be transmitted to the outside and ideally where things from elsewhere could be transmitted to the building and processed and re-enjoyed. And also it was a place where genuine information would become accessible to the world at large. Now, this was quite controversial in France. We were aware that the French media was entirely controlled by the state. So, this was as radical a statement in terms of the politics of media as it was anything to do with building. The state controlled media; there was not ITV equivalent, it was the state in control. France is a much more right wing country than the UK, even today, if you look between the lines. But it was very important that it had these two or three messages. First it was this machine if you like, which housed a range of activities, the brief was very important. I’ll come back to that in a minute, and also that the accessibility was demonstrated, that you could read the building, how to use the building, how to go up the building on the outside, nobody has ever asked me how you go up the Pompidou Centre—laughs.

![]()

fig. 2

Centre Georges Pompidou section

Paris 1971

It was a very strong section, it was lifted above the ground, the ground was seen as public realm, and most of the specific activity was lifted above, and maybe most important of all, at the time there was this notion of neutral flexible space, which has in fact driven all the work of the practice ever since. Not forgetting what was on the top of the building, that was a new symbol of the time, which was a new idea of transmission of information beyond local boundaries, so that one was connecting at a distance, the world was just opening up in terms of information flow. As I mentioned, the three-dimensionality, the verticality, the services of the building, on the one side the public, and on the other side, the technology required to support the activities. The vertical was much more emphasised by the fact that it also went down into the ground, and the elevators went all the way down, it was a Y shaped system with floors that sat in-between. In the original competition, the floors were thought of as movable floors, which means you could adapt the heights and that gradually dissolved as the project went on to David Greene’s disgust, but we can come to that another time. It was an extraordinarily expensive move, and it was of course the budget that eventually killed that for the simple reason that they said: “this one, but tell them that they’ve got to half the budget that they thought they had.” So the competition was clear, the idea was clear, the notion of the building was really strongly marked in drawings that were rather simplistic, slightly naïve, very diagrammatic. We had tremendous resistance from the French government to the shape of the building, and the general reaction was, couldn’t we smooth it out a bit so that it tucked in to the quarter rather than aggressively sticking up much higher. And for several months we worked on a scheme that became known as the jelly-mould scheme, where the ends of the building were eroded, so the aggressivity of the frame was nibbled away.

![]()

fig. 3

Centre Georges Pompidou model

Paris 1972

We were basically really strong engineering lovers. We’d been drawn to all the great engineering of Europe, and the assembled team was an incredibly technologically proficient team, so it was no accident the building is the way it is. Richard’s not a great technologist inasmuch as he’s not the practical technologist, he’s technologically amazingly intuitive, but he surrounded himself with a team who were people who could actually deliver technologically advanced projects. It was a unique moment from that point of view. It was an incredibly strong team that assembled in Paris, in the heritage of great French engineering. And just because you’re architects (reaches into a plastic bag), this is a piece of the Eiffel Tower. It’s original. It’s about one hundred and seventy years old. And the French government gave it to us, because we were considered fanatical lunatics about French engineering. We went everywhere and climbed everything we could, up the Eiffel Tower, walking all the way, which is quite an extreme experience, and very scary, and you were close-up to pioneering engineering. If you look at this piece of the tower, it’s not precise, it’s not an RSJ, it’s pre-RSJ wrought iron steel made into a very efficient piece, it’s phenomenally heavy, I can’t imagine what the weight of the Eiffel Tower is. It was given to me because the man doing the secondary steel-work on the Pompidou was the engineer who had been asked to adapt the lifts on the Eiffel Tower, and they had to cut out two old beams and put in new RSJ’s to support the new lifts. And he said: “well, I know the fanatics who are going to love a piece of the Eiffel Tower!” So I’m the proud owner of a piece of the Eiffel Tower. So as technologically strong people rather than architecturally image based people, which we also were, but the integrity of the project was about the great engineering statement of it, and about the notion of flexible space for use. So, the machine was there, but what drove us was the idea of how the building would be used, this sort of openness. So went back to the original diagram, away from the jelly-mould and back to the clear original idea in various forms, which was very important. And that took a year of hammering it into the politics of the French government, who were busy trying to smooth it off. In the end Richard went to Pompidou and said, “look, we can’t do it, we have to return back,” and in the end Pompidou said: “I’m not in charge. I leave the decision to the head of the EPCP.” Which was Robert Bordaz, who said: “We stay where we are, you’re the architects and we respect your decision.” In France architects are far more respected than in the UK. This is quite a late drawing.

![]()

fig. 4

Centre Georges Pompidou signage graphic

Paris 1974

It was by the signage people, but it captured the spirit of the original building, and we were then beginning to work out the building in detail, and there were proposals for signage people who were local, and one of them captured the sort of spirit of the building, which reinforced the idea of going back to the original concept.

As the final set of drawings began to emerge, another space that is glued on to the Pompidou piazza, which is the Place Saint-Merri, which didn’t exist in the first plan; in the competition it wasn’t there, then the French government managed to get hold of the site by demolishing a school, and that became part of the Pompidou site as well. The plan is very clear. The ends are open, the building sits hovering above the ground and the piazza is a very large public place. We were building models all the time, we consistently had a big model making team, and we have a big model making team today, and we built models all the time of every piece of the building, small scale, large scale or full size, because it informs what we do. There’s a continuous dialogue and our model makers are very fine architects. They are not formally trained as architects, but the architectural critique of our model makers in the office is as highly respected, as it was at the time. We kept working through models, and of course the model is still a great way to explain to the client what you’re doing. The plan is incredibly simple, two spaces, served and servant, that’s all it is, people on one side, technological support on the other and completely neutral space in the middle. That’s the power of the plan. If you think of Lloyds, Reuters, they carry the same message right through.

The section is very important. The piazza was really critical. We saw two piazzas, the piazza that was the ground, and the piazza that was the façade of the building. We saw the façade of the building as being as important as the ground, because it was something in control of the building; it was a way of manifesting what was inside the building on the outside. But we were also challenged by this enormous façade, which was one hundred and seventy metres long, very tall, and we were worried by the flat façade, and if one looks at it carefully, the façade’s got seven different layers of materials. We called it the dance of the seven veils, because there is no simple façade. I challenge anybody to draw the actual façade itself, the weather enclosure of the Pompidou Centre, and tell me how much glass is in there, and how much solid material is in there. You’d be surprised how little glass there is in it, but it still works extraordinarily well. There are many layers and the building didn’t stop at the traditional façade line, but came all the way out to the outside. A key point is that it’s a very big building, and only half of it above the ground; the other half is below ground. There are huge vaults housing national treasures of fabulous value, obviously the great art, car parking, huge technical plant areas and a road which runs through the south part of the site, which of course everybody forgets, which had to go through our building and IRCAM, a building we did later. We began to define the building and rushed through, great drawings, all hand drawings, we used Rapidographs but my friend Laurie Abbot, who drew this drawing, felt that Rapidographs weren’t precise enough and he went back to a graphos pen, and used to sharpen his graphos to get these incredibly fine lines.

![]()

fig. 5

Centre Georges Pompidou detail drawing

Paris 1974

The problem was, he’d draw so perfectly that drawing just fell apart into pieces because his graphos just cut it up, but that drawing still exists. They are wonderful drawings, like tapestries, you zoom in and they are absolutely beautiful, drawn by people who were very powerfully equipped, we knew about transformers, pipework, duct-fixings. We also built it in model form, and we coordinated it because the one thing we were capable of doing was organising the technology in a way that was more than just technically technical, it was rational, functional and beautiful. We designed the chairs, the tables, the library equipment; we were involved in all the details of the design, with local French firms. We designed everything in detail, great engineering and good architecture together. We were privileged to have excellent engineers, and the notion of casting the building elements developed because they were highly repetitive, especially the ‘gerberettes’ (cast steel arms), which were massive, this is the elephant’s graveyard, in Strasbourg, where they were just dragged out of the mould, and laid down, and they attacked them with giant machines, flame throwers and big grinders, to try to tidy them up.

![]()

fig. 6

Centre Georges Pompidou gerberettes

Paris 1975

C/O Centre Pompidou

One of the great things about the project was the arrival of the beams from Germany; they were made in Germany, it’s too long a story to tell, maybe later. This was a real event. These things are a hundred metres long; the beams themselves are seventy-two metres long, and with the crawler, one hundred metres.

![]()

fig. 7

Centre Georges Pompidou trusses

Paris 1976

Now, think of Paris. Can you imagine getting these through Paris? It was a nightmare. We demolished virtually every piece of street furniture, and we were all out of course, all night sessions with good alcohol, good wine, walking alongside this real event, as the first beam came through. They all arrived and it became an immense building site. The French architects fought us for three years bitterly, but once they realised they couldn’t stop it, they became very friendly. Look at the height of the building and the height of the French roofline.

![]()

fig. 7

Centre Georges Pompidou on site

Paris 1976

C/O Centre Pompidou

It was cheeky and I think Renzo called it ‘loutish’, an act of loutish bravado, he said that recently of course, he chickened out because he now has to deal with cuddly American museum clients, so he’s got to say that, you know. We had the biggest hole in Paris, it was an absolutely gigantic hole, at one end it was an empty hole and on the other end we were building the building. We moved all the rats in to the prostitute street, that wasn’t popular. Finally the building was completed, and after the final clean-down in 1977 we opened, and the architect was never mentioned by the president, who didn’t like the building. We were a bit disappointed by that, even our egos were a bit deflated by that, and secondly, they didn’t allow anybody on the piazza, because, “this was a national museum, you can’t have the public in the foreground!” We fought for six months with the prefect of Paris saying: “the whole idea of this piazza is that it’s a public place, it’s meant to be used.” After six months it unlocked and all the people flooded in, which in the summer is an absolute delight. The library was mobbed from the day we opened it, and has never been free since. It’s been taken over by the students of Paris as the first open library. It was and still is fantastically popular. In the end it was about use, about flexibility, growth, change and connectivity and openness. And it was then, and it is today.

PENNY LEWIS

The thing that struck me about your presentation Mike, before we talk about the legacy, and I think the legacy is important in lots of different ways, was the incredible sense of energy and optimism that came across from those drawings. One of the reasons why we wanted to have this discussion was because Samuel and I felt that there was a very different attitude toward building technology today. What happened to the engineering fanatics, either inside yourself or more generally? What do you feel has changed that outlook?

MD

Well, the engineering fanatics are still there and still love the production of physical things, whether it’s an adobe wall, beautifully made, or whether it’s a piece of fine steel-work, or traditional brick-work, it makes no difference, fine work is just a joy, and is as much a joy now as it was when we were younger technologists at the time. And I think there’s radical technology happening all around us, it’s at a micro scale, but it’s just as radical, and just as socially changing. The pill and the microchip have radicalised the world in many ways, and the next way will be dynamic buildings. We’re going to be in a position where building materials will change their state properties. You can begin to see it happening, windows that can change from clear to white, reflective, which is basically nanotechnology, materials in clothes that glow, which heat and cool. If you look at the nanotechnology industry, it’s all building up at the present moment and it’s going to suddenly spring into our world, into the physical world of the human scale, and it will change buildings. It’s just beginning to do so. So, just as the industrial revolution, which I absolutely loved, I used to worship at Iron Bridge, which is one of the great shrines of the world, if you enjoy that sort of thing, then the second industrial revolution which is electronic, and the third, which is chemical, and the fourth will be chemo-biological. It’s happening as much today as it was before. The Himalayas are moving uphill as fast today as they were ten million years ago. It’s alive and changing at the moment. And I think David Greene was not correct. He was my tutor and my close friend. He’s one of the great arch-prodders as well as a fantastic teacher, brilliant at making you think laterally, to think outside of the box. But there is the chip on the shoulder between the academic who hasn’t built, who couldn’t force himself to even have the opportunity, and those that are out there trying to persuade clients to move a little bit further. If you can move a few clients, a few states, a few city governments, a few planners, a few centimetres in the right direction over a very large field that may have more of an effect than a radical building idea. But I agree with Kester that the building was radical. Incidentally we’ve never objected to its modification and never objected to its demolition. You know, people say I did the Dome, now I’m not allowed to call it the Dome anymore or you get sued, it’s the O2, but you know, of course you take it down when it’s finished. It’s a lightweight tent for god’s sake. It cost forty-three million pounds, unlike the messages you get from the press, the same price as a supermarket shed, and it’s demountable, as simple as that. We’re very much into the notion of things being adaptable. But I think the point that Kester made about nibbling away in the real world is really important because everybody in this room is nibbling away, everybody is trying to explore new fields, explore new materials, or using existing materials in beautiful and magical ways, and it’s not big names like our practice is a big name now, but we were a small team then, and our practice in California was six of us, three artists and three architects, and we had the most wonderful time. But I’ll come back to the Pompidou. I’m roving a bit. One of the reasons the Pompidou worked was because we had a unique moment in time, you had the intent of making a special building, which may have been a response to 1968, but funnily enough we didn’t read it like that, and Richard didn’t and Arup’s didn’t, we didn’t politically read it as much as the French. It’s easy in retrospect to make those connections. But we weren’t that connected to France, it was abroad, it was somewhere else. The response of the building was more to do with information, rather than saying: “how do we sort the French Left out?” My wife was chucking cobbles in ‘68, she’s French, so I have connections directly back to it. But the most important thing was that you had three great clients, and a great client leader, which was a rare opportunity. You cannot do a great building unless you have a great client. We had three great clients in the Pompidou Centre, Bordaz with fantastic vision and solid hands, and then there was Pontis Houlton, Sagan, in the library, were all radical thinkers in their own fields. Pompidou was unique, there was a moment where client side and the architectural and engineering side were all on song, so it was a unique moment, and with a very strong team. I’d pit the team against anybody in terms of ability to deliver things. It was quite phenomenal. And there was this lifting of the French state’s hand, which I’m sure, was a post-68 phenomenon, and it all came together. There were great moments. But perhaps the most important thing of all was that we loved each other’s company. We were a real team and I think really good projects are partly there because the team works. If the client loves the architect, and the architect loves the client, in the sense of respect, and there really is a dialogue, then you work together. At our Monday morning meetings all the partners sit together and we’ve got very different expertise, and you watch a project that is up for crit on a Monday morning at our design meeting, and somebody moves something up, and you watch the quality of the project going uphill, it’s a magical process, and it’s only possible if you respect each other, and the rules of the game is that your criticism has to be positive, not destructive, and it’s fantastic. And that’s exactly what happened at Pompidou. And the President’s wife was fantastic. Madam Pompidou was a dream. She was an art collector of great quality, and she drove a lot of it in the background. There were common motives from all parties.

PL

It’s good to hear the discussion about the client and the competition process, but just briefly, Kester, sticking to the question of technology, I mean there is a sort of suggestion from the more contemporary reviews, and even ones that come out of your Supercrit, that there’s something sort of fetishistic about the technology, that it’s an add-on. And I think Rogers makes the point that actually they were very inspired by early Modernism, not just Archigram, they were inspired by Constructivism. There’s almost a sense that the enthusiasm for technology was a response to a moment that had passed and that it was reflecting a relationship between program and technology that maybe belonged in the 1920s or was maybe expressed in the 1960s but couldn’t be delivered. I’m just interested what you think about the place of technology in this building?

MD

Didn’t you answer the question earlier Kester when you said that it was not important as an object, but in the way it was made and the way it’s used? I thought that was a wonderful description of it.

KR

I think that’s right. The name Hi-Tech was kind of a joke originally, like High-Gothic or something like that, and I think there is something a bit fetishistic about it, but so what.

MD

Well, I don’t think it’s fetishistic at all.

KR

I think it is, but I think the point is more what it does, and I think in this building it’s really clear that’s what they are trying to do. I mean the whole gerberettes thing is slightly arcane. I remember being completely baffled by what these things were, when I was a student, looking at these thinking, what do they do?

MD

They’re the brilliant original engineering of the building, and I could give you two a lecture on the balance and the equilibrium, and how all the tension is taken to some-place, all the compression is taken to others, and how by doing that, the columns can be very small, the gerberettes take all the lateral twist out and then you can make the columns remarkably thin, if you prop them regularly you can make very elegant thin things.

PL

In that Denis Postle movie there’s a great long sequence with Peter Rice doing a building up of the model and showing how it works, which was actually when I really understood it.

MD

It wasn’t narcissistic technology. It was great engineering. Peter Rice was a great engineer, and not the only one. Remember behind the name there’s a big team. Lennart Grut was there, who’s a partner at Rogers now, ironically, still there after forty years, and it’s forty years in January that I joined the Pompidou team. They were engineering concepts, they weren’t to do with an architectural style. It never occurred to us. We just responded in the way that was required by the brief to do with long spans, free span spaces and so on, and then making it as delicate as possible from the outside, to keep it as transparent as possible, as legible as possible, also the way it was assembled because of the technology of the time, the rationale of putting Meccano together was the way to do it. It was done quickly and so on, in the middle of a city where you could hardly park a car let alone park two hundred metre long beams and manoeuvre them around. Like Lloyds, how the hell do you build these gigantic things in the middle of cities where you can hardly stand beside each other? It’s fascinating, just the construction of these things is a wonderful business. The construction of big buildings in complex cities is a fabulous story. Maybe I’m just a nerd about project management, I don’t know.

PL

Okay. I’ll open it up to the floor.

AUDIENCE

I very much enjoyed your explanation and evocation of the kind of enthusiasm for the technology and the things that truly democratic architecture at that time could do. But I think there are certain quite fundamental criticisms which come to mind, and with which I’m sure you’ve discussed many times, and I just wondered if you could maybe respond to that. I think not everyone is as enthusiastic about the possibilities of technology as you clearly were, or still are. I mean, the doctrine of progress has become a little bit threadbare, and I think preferring technology to the quality of space that people can use, and I’m talking primarily about the quality of internal spaces, with great big trays of space that don’t really have very much daylight, which don’t have any kind of internal organisation and where the museum has had to be built inside, that seems to me one of the things I regret about the project whenever I go there. The other question: as wonderful as the piazza is in urbanistic terms, and I think in some ways the fantastic popularity of this space, is as you said, a victim of its success because the whole neighbourhood has become unusable for a lot of Parisians in what has become such a tourist circus. But that’s beside the point. I’m thinking of the backside of the building, where the ducts are, and where the homeless now camp; I mean, the fact that this building really turns its back on a major public street, and really does very little for it, in fact it’s sort of blighted it I think. Those would be my two main reactions. What would you say to that?

MD

You said that you regret that the museum had to be built inside. But that’s exactly what the intention was.

AUDIENCE

I just think that this idea of flexibility, neutral space that is serviced on the outside, and you can do whatever you like on the inside is an appealing idea, but I think is in actual life things rarely happen that way. A lot of temporary architecture, a lot of flexible architecture stays set for decades. I mean, it’s very difficult to hang art in a space like this, so they’ve built the museum inside, and the offices as well. So, there’s this kind of warren of glass corridors when you walk to make the offices habitable for the office workers, likewise with the library and so forth. I mean it’s wonderful that this building exists and we can see all this in action. But it seems to me that it’s not an ideal place to work, or to use the library.

MD

Well, I think the process of institutionalisation is a part answer to that question. Everybody’s backing in to their comfort zone, that’s back towards traditional building, and I think that’s reasonable to do in part. This is the only building that we really know that posited this notion of the loose-fit, and I think in a world of basilican museums where you’re restricted totally by the shape of the building, as to what you can hang, and that was the big complaint of the head of the art gallery, he said: “I’m fed up with curating things when I can only put seven Rembrandts in a room, when I want to put ten together, and I want a place where I can make the rooms suit the work.” That’s exactly the drive that the museum had. They said they didn’t want a space that they had to react to, they wanted a space that was neutral, ideally with no windows at all, museums hate light, and then they could build the museum they wanted inside to suit the exhibit. I’ve been to thirty or forty great exhibitions there, where the interior is totally different in each case. So in some way we reacted to the passion of the museum Zeitgeist of the time, we were not museum experts, which was for less restricted, less basilican forms of spaces. And if you like, the spaces between Tate Britain and Tate Modern characterises it, one where you have to accept the building absolutely and if it’s done well and beautifully curated it can be magical, but you’re absolutely straight-jacketed by the size of the prescribed spaces, if one was looking for flexibility in height then I think Pompidou provides you with some problems, if you say you want to inhabit the place with offices, then I do think it presents some problems, I wouldn’t disagree. It was an experiment. On the one level it was seen as: “let’s have a go!” Because there were ten thousand museums around the world of the other sort, let’s go for one, or try one, that would explore something else, of which some things wouldn’t work, I’m sure that’s true. I worked in the building for two years, we moved our office into the building, and it wasn’t a great office space. And I think if you’re going home from a nine-to-five then it must be a bit tedious. If you’re impassioned by what you do it doesn’t matter what space you work in, in my view, you manage. But that’s no defence. But I do think the museums were about exploring the kinds of things that you find ironical about the building. In term of the Rue du Renard, it was much more open when we opened. We had fourteen entrances to the building, and I think we had six entrances on to the Rue du Renard, it was fluid, it was open, what is now closed was open and you could flow in from anywhere, the whole idea was that you could flow right through the ground-floor, so it was much more open. And again because of two things: one thing was museum security, those chairs we designed for the building, two hundred of those chairs were stolen in the first week—laughs. And I don’t know where any of them went. It was extraordinary, absolutely amazing. So there was a problem with security. I mean, we were young liberal hippies from California and London, and the idea of people stealing chairs never occurred to us. But basically there were security problems, and then later security started to become a lever for all sorts of strange control devices, security cameras everywhere, only one door, Gendarme’s checking you in and out, which is a security device, Al-Qaeda Tupperware parties not accepted here thank you, but that’s the nature of the beast, and in a way it’s part of becoming more institutionalised, and in some ways is retuning to that which you may like more. But I don’t think it unreasonable, at the time, for our passion to support the idea, which our client also was carrying, of experimenting and seeing if you could do things a little differently. If you go to the National Gallery extension in London, which is a mockery of a great building for me, you’re completely straight-jacketed by the concept, and you have to fit in with it and have to fit all your work around it. And addressing some of the questions about technology earlier, it’s not a technological building for us, because it’s not been covered up by a stone façade, it’s just there, it’s somehow technological. Look at Michael Hopkins’ building at Westminster, it’s a technologically advanced building, but it’s made of stone, the technology’s there, it’s just more discrete. If you said it was overt I’d accept that, but somehow the technology’s in all the buildings and it’s just a matter of whether you play it up or not. We didn’t play it up, we just said, we can’t afford to clad it with anything else, and we don’t really want to, we want to leave it the way it is. But we weren’t trying to celebrate it. I can’t imagine any motive for us to say: “let’s put this up front, and let’s knock people’s teeth out with it.” It was just what was required to do the job, and it seemed to be in the absolute spirit, I mean you stand beside a great bridge and you don’t clad them in because of the nasty wires, you just accept the way it is. Bridges are more beautiful than buildings generally because you’ve got this great line in scale because of they are very large-scale object, and generally the landscape in which they sit is very simple, which means you can read it as an art objects as much as a technological object. In the city of course it’s different, you get all this mishmash, but then that’s one of the nice things, I think juxtaposition, if you go to Oxford, look at Oxford High-Street, there’s not a single building that lines up with anything in sight anywhere, it’s an amazing rich complex diversity. It would never get planning approval in a million years now. So, I like the juxtaposition, but we were at no stage trying to, I can’t think of any moment when we sat down and said: “let’s celebrate the technology.” We were just getting on with putting it together. I mean, looking at it standing back, it’s technologically very strong, without doubt. But there was no intention to make it technological. Remember, there was a very strong engineer in this process, not just the architects. I can’t draw a line between the architecture and the engineering, which I can’t really in any good building actually. I think the engineering was exceptional, and we appreciated the passion and the power of the engineer, which has imposed itself on the architecture. The engineers were wrestling with the problems of extreme proportions, because that building is loaded to twice to loading of normal museums, more than a ton a square metre so we could put elephants on the Pompidou on every square-metre, and incidentally, the deflection of the floor mid-span is thirteen centimetres under full load, it’s quite substantial.

KR

Was that required?

MD

That was required, no no, part of the brief was: “We want Henry Moore sculptures packed side-by-side, shoulder to shoulder, solid bronze, all the way through the museum.” That’s about a ton a square-metre, which is about eight times the loading, if you put cars on the floors, it’s pretty prodigious, so, there were engineering challenges which look easy now, but were absolutely at the limit of the technology at the time. And the gerberettes are cantilevers backwards into the building. The gerberettes reach back behind the columns into the building so that you can reduce the span of the main beams. Of course there was the question of how many floors you could get in before you were too high for that fireman’s ladder, so we had all the usual struggles in how to optimise area and span and so on. It was a technological response. You could say, it’s uncivilised; if you’re a great lover of Paris, and I absolutely love Paris, and I think the great juxtaposition make life even more interesting than if it’s all the same. I can think of countless positions around the world where the juxtaposition is the richness, rather than all being respectful and similar.

KR

Going back to the argument about surrounding buildings. It was the one that was being had while I was a student as well, that the houses opposite, on the other side of the piazza were the really flexible ones, because in their time they had been houses and shops and restaurants and brothels and who knows what, schools and all sorts of things, and that actually rooms are a terribly flexible thing, walls that you can knock holes in, that’s another type of technology as well. But there’s something I wanted to ask, which was kind of connected, was it a gas-guzzler? Because it was the age of cheap energy wasn’t it, very deep plan and that kind of thing.

MD

The deep plan’s an advantage. Go to Canary Wharf. Look at those guzzlers at Canary Wharf. Look at them carefully and you’ll find they’re the exact opposite; they’re extremely efficient because they’ve got such a deep plan, that the edge condition doesn’t affect the middle of the buildings. So the solar diurnal movements don’t necessarily flood through the building, and with very large numbers of people you can start playing the building as a buffer against the environment. So ironically, the deep plan helps. In a museum, being a long way away from a hot or cold wall helps, and a museum has quite specific conditions. The humidity is just as controlled as any traditional museum. But I think it probably was a gas-guzzler, although remember, the Rue du Renard has no windows on it at all. There are very few windows in the Pompidou Centre; I don’t think there’s more than fifty percent on the west piazza side. You’d be amazed how solid it is, so it’s not thermally bad.

PL

Returning to the question of flexibility. One of the things that always strikes me is whether our anxiety about its flexibility is more prompted by what came after it, about what is being built at the moment. The problem is that ethos seems to dictate a lot of architectural production today; that the demand for flexibility is not about the program but a lack of commitment by the client body, and in terms of people really thinking about what culture might be. I’m interested actually in some of the comments that Colquhoun made at the time that it was built, because he’s from a different generation of critics who were clearly much more part of that tradition of dealing with Modernism in a different way. And actually some of his criticisms hold very fast today. Not particularly in terms of the Pompidou, but in relation to contemporary practice and the way the buzzword of flexibility is being used to justify the denigration of what it means to let the architect lead the process. Are there any other questions from the audience?

AUDIENCE

Yes, do you think you’d have a hope in hell of winning this competition today?

MD

I don’t know. I don’t think you win competitions on the design. I think you win competitions on the idea. And the idea of the time was to do with the issues we talked about, more than the images. I think what drives the big debate is still the idea. We’ve returned to a different world from the time of the Pompidou. We’ve gone through Postmodernism, the complete loss of direction, and we’ve now returned to two things; a sort of genteel Modernism, characterised by people like Allan Stanton who worked on the Pompidou, he does very beautiful buildings, calm and very nice, or, mad funky form, which is the other group of people who I don’t need to mention because you know who I mean, doing incredibly expressive things where structure is irrelevant, and where you can put as much steel as you like just to make sure the cantilever looks okay and so on, but neither of them have the ethos we did when we built the Pompidou. Now I think we’ll see the development of another kind of architecture because I think there’s a conflict between the state and the people at the moment, and which is beginning to build up because of the economic situation. If you look at the map of the riots that have happened in England recently it’s striking. I’m doing a big project in Paris, which is to do with urbanism and studying deprivation and interventions, and the correlation between the poorest areas and where they lived, not where they rioted, but where they lived are almost absolutely correlated with poverty. And of course the government said this has nothing to do with poverty, and actually lo and behold, the actual facts, and I think that’s an actual problem. We’re rather privileged in this room, to talk about buildings in the way we talk about them. There are going to be some very big problems to do with habitat, housing people and so on, so we may end up with a new architecture. I remember when I was at the AA there were passions about the politics of the time. One of the units was a young bunch of Scottish tigers called Benson and Forsyth, they were great, they were fantastic, and they ran a white modern, rigorously tough architecture unit at the AA, and they were terrific and everybody admired them. They didn’t tolerate any crap; if it wasn’t Corbusien forget it! And in the same school in the same year there was a unit run by David Wild who were fabricating paper bags and printing them with the Vietcong flag on them, selling them at Trafalgar Square and sending the money to the Vietcong. So you did have differences of view, in a good architecture school you should. I was privileged to go to a very loose-fit school. There wasn’t a deliberate agenda. The intention was to offer a range of agendas, from Benson and Forsyth to Archigram and all the rest of them. Cedric was my tutor, and he was absolutely devastating; he chopped you into small fine laminations at every crit, you were completely devastated, you wanted to jump off a bridge because you knew life had ended, it was complete demolition. Not all architecture schools have that range or privilege. We have to keep the range in architectural schools as wide as possible, which means selecting tutors who are of a range, so they’re not all similar tutors, and I think one does have to be open to politics, because as Richard said in ‘Supercrit’, he does think that architecture’s a political act. It’s not something you do as an art alongside political life, it is a political act. And I think in the next few years we’re going to be into political architecture and we’re going to have to do some things we haven’t had to do for a while.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()