CONTACT

Custom Lane,

1 Customs Wharf,

Edinburgh,

EH6 6AL, United Kingdom

mail@aefoundation.co.uk

DIRECTORS

Nicky Thomson

FOUNDING DIRECTORS

The AE Foundation was established in 2011 to provide an informed forum for an international community of practitioners, educators, students and graduates to discuss current themes in architecture and architectural education.

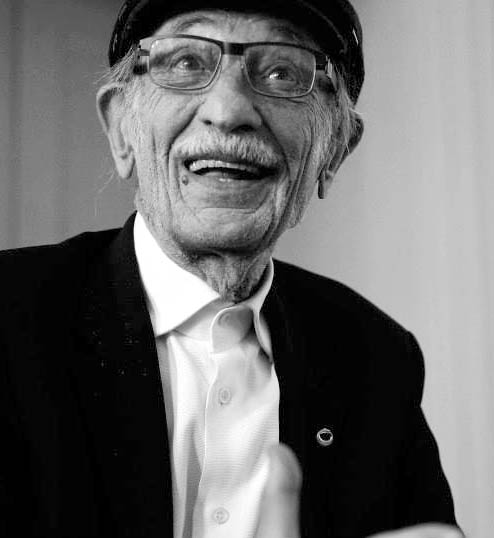

LUIGI SNOZZI

︎︎︎Penny Lewis

︎︎︎Samuel Penn

Translated by Jenny Dubowitz and Daniel Serafimovski

PL

Could you please talk to us again about your approach to education? You spoke in the lecture about how it might be more useful for the student to start with the city and to end with the family house. Could you tell us a little more about this? Why is it important or useful?

LS

I would say the biggest problem today for architects is the city, and for that reason it is important in architectural education to start with the problem of the city. Whereas usually in education one starts with a small project a little house or something like that, I think that instead I would rather start with giving them a piece of the city to design. You first have to learn about the city and then you can do a house because that is in a sense out of context with the city and it’s the most difficult project because every single room has different requirements; living room, bedroom, kitchen and so on. So every room is like a world of its own and obviously it’s different for every family and every client. Also a single-family house is small and doesn’t have repetitive elements, repetition which for architecture is fundamental, for the city it is fundamental. To be able to create a rhythm. I think the single house is the most difficult project and it’s better to leave it to the end, when one already has experience. In Sardinia, where I teach, the students start with the city and end with a house as their thesis project.

PL

What does the first year involve? What is involved in looking at the city?

LS

I would choose a city or a complex piece of a city and give it to the students without any programme other than: in ten days you have to put in order the city centre. For example Trieste which is a very layered and complex city; you’ve got Romans, things from the Austrians, you’ve got the fascist period and so on, and it’s incredibly complex and difficult. I give this to the students, and in ten days they have to put it in order. It’s like taking a new-born baby and throwing him into the sea to see if they can learn to swim. So of course what you get are all sorts of unimaginable proposals. They don’t know how to draw, they are only starting to learn how to draw. So you get all sorts of projects. But I’m convinced that by the end of the year they end up by loving the city. For example in Sardinia I choose to work with the fascist cities, designed during the fascist period by Mussolini’s architects, because they are the most interesting examples, apart from the ancient cities in Sardinia, and also because, as they are anti-fascists in Sardinia, they don’t like these cities because of all the memories of the war and so on, and they mix politics and reality. They are not able to appreciate these cities but they are actually very valuable. They are the best examples of city-making. That period, the beginnings of fascism, was the last period of really good architecture in Italy.

PL

And do they make a proposition for a building, or is it just about understanding the city?

LS

They draw a piece of the city at a larger scales, at 1:1000 or 1:2000. They don’t get to design a building yet.

PL

While we are on the subject of the city, Corbusier and Rossi are your two main influences. Are there others?

LS

In terms of the city the largest influence was definitely Aldo Rossi because he was the first architect who showed how cities developed. He quite concretely explored and explained that. Of course before him there were others like Camilo Sitte but they didn’t ever deliver a discussion of the city in the same way. And Corbusier provided very good examples of how to make a good piece of architecture. In terms of the language of architecture for example the project for the hospital in Venice, he does a project which doesn’t have anything to do with Venice in terms of language. He uses concrete, he does flat roofs, he does pilotis, in Venice you don’t have pilotis, you have them only below the water. He does strip windows rather than vertical windows: everything opposite to Venetian architecture, but nevertheless he manages to come up with a project which is truly Venetian. And the reason why it is such a successful project, or such a Venetian project, is because what Corbusier does is that he doesn’t use language, stylistically, but he uses the morphology of the structure of the city. So the relation between water and land, the existence of very narrow streets, little squares, and he reuses these in his project. So for example Gardella uses all the Venetian materials and architectural features, for example vertical windows, but he makes them somehow more modern. He uses marble on the base of the building, render on the upper part of the building. So he transforms a typical Venetian house into something slightly more contemporary and this is an example that has been used over the last 50 years, still today, as an example of how as an architect one should work in a historical context. But I think it is really a disaster and that it should be ripped out of any book of architecture.

PL

Is there a danger that people understand Rossi’s work as existing within that tradition, which you say is problematic?

LS

Yes. Rossi is a very particular case. He works with ‘type’, not with architectural elements. He is not capable of working with architectural elements. In fact in all his projects he doesn’t even build them himself, he didn’t construct them. He doesn’t build them himself, and in that sense he is not an architect. The only project of Aldo Rossi’s that I am enthusiastic about was a small theatre, the Teatro del Mondo, in Venice that was built for the biennale. The one that was floating, the timber structure.

PL

Why that one?

LS

I saw it on a beautiful foggy day in Venice. You couldn’t really see very much and then suddenly I saw this thing appearing and floating, sailing by. And it gave me such a strong emotion that I couldn’t forget it. There was something in that project that was very Venetian, that belonged to Venice.

PL

It belonged in terms of the imagination?

LS

Yes, of Venice.

PL

And the earlier work like the Gallaratese?

LS

Of course some of his earlier work was very strong, for example the Gallaratese. It is an important building.

PL

You clearly feel that Rossi makes an important contribution but is not an architect. In terms of the relationship between Corbusier and Rossi, the influence Rossi had on you, can you please reaffirm what that influence is. Why Rossi is important?

LS

Rossi gave me the tools with which to look at, and analyse and understand the city. So it’s not so much for his buildings but more for his theory. Between the 1960s and ‘70s we did extensive surveys of cities in Ticino together with Vacchini and Carloni, and we surveyed all of Bellinzona, but all of it, all the levels of the houses, of every house, from the ground and up to the roof. We were supposed to develop a kind of urban plan, a masterplan. And we felt that these surveys were important or fundamental in order to understand the city. But actually we ended up doing the worst masterplan we ever developed for a city. So these survey drawings weren’t useful. Contrary to this I gave my students at the ETH various bits of Bellinzona to develop, to do proposals for, without showing them the surveys that we had done, and they ended up doing very, very interesting work.

PL

Why?

LS

It is not necessarily true that studying a place in a lot of detail will lead to the best possible solution, it could help, but it could also lead you astray.

PL

Is that a problem that we see now in terms of the paralysis that sets in through the collection of data or the analysis being overly dominant in the process?

LS

In the ‘60s and ‘70s our studies were very profound, very detailed, very rigorous, but now the types of analysis and surveys that are done are not necessarily scientific, but they happen to analyse whatever comes into mind, sometimes things are totally relevant or whatever happens to be the caprice of the professor or whoever sets the brief.

PL

It is interesting that you use the word ‘scientific’. By that do you mean more architectural?

LS

More scientific, more correct, systematic and that follows certain principles. Now one does readings of the city that are a little bit more fanciful.

PL

So, Rossi is very fashionable at the moment. How do you interpret that?

LS

I worked alongside Rossi as a visiting lecturer at the ETH in Zürich in 1973, and I was very intrigued. I would go to Rossi’s lectures, to see how he was critiquing his students. I remained very disappointed with Rossi because the lectures were bad, because he was reading from his book in German. His German was terrible so you couldn’t actually understand anything. Secondly, in those two years, I never heard Rossi critique the actual projects, he would go to the rooms with the students using (spray gun/airbrush) and they were putting clouds in the drawings and so on, and the only thing I ever heard him criticise was: “make that cloud a little bit darker.” Or: “this is a really nice place to put a good cloud.” He didn’t critique the actual work, the architectural projects, but on the other hand he had very good assistants from Ticino and they were carrying the Rossi flag, they were his soldiers. They would be tough with the students whereas Rossi would be floating around like an angel. So even though I was disappointed that Rossi wasn’t particularly interested in teaching directly, I understood that its possible to be a very good teacher, professor, without talking, just by being there, by sheer presence. It’s enough to have the presence. Of course this relies on doing something before that he already had, because he had written the books and so on. Another example about this relation between people that is quite mysterious. I only met Corbusier one time when he was doing a lecture in Venice, and Galfetti, Botta and Vacchini and I, when Corbusier passed by ran out and touched his jacket with the fingers of our right hand. And for the next two weeks we didn’t want to wash our hands, so we ate with their our left hand, drew with our left hand etc. The point is that this kind of moment, this interaction, meant much more than listening to ten thousand lectures by Corbusier. But of course for that to be able to be transmitted it was important that that person had actually achieved something important, which of course Corbusier had.

PL

A question about Postmodernism. Do you recognise it as an idea? It is always seen that Rossi and the people of that period are a reaction to Corbusier, whereas you stand in a tradition where you can take both of those things.

LS

In Switzerland almost nothing came of it. It was Aldo Rossi who introduced Postmodernism as a movement without intending to.

PL

There are a couple of contemporary themes that came up in the lecture. One was the Dutch project, why they were excited about circles, the discussion of whether architecture could be democratic, and about uncertainty and doubt. Why did people react so strongly against the scheme, calling it fascist.

LS

The Dutch were against the use of the circle because for the Dutch, and I call them ‘falsely democratic’, the circle represents something absolute, a single form with one centre—the point. And so in fact the Dutch government had sent a few people to check on what I was doing and making sure that I was not doing a circle. They asked me to alter the shape to make it more amoeba-like, introduce several points within this centralised idea, so there is not a single central point, because that for them was quite fascist. They felt strongly against someone coming from outside from Switzerland and imposing or suggesting something as finite as the circle, which for them was not suitably Dutch.

PL

Is that because Dutch society has a problem with the absolute form or they have a problem with the sense of agency that comes with that? The control of the individual.

LS

I think that it was a bit of that. They didn’t like that a foreigner came to Holland to impose an idea, because they were a democracy and in a democracy there are ten thousand ideas. And they didn’t like that a foreigner came to impose a truth. For them the circle was God, the only God, that’s all. Nothing else. And this they didn’t like. Impossible.

PL

We think that that is not just a Dutch condition, that it is a generalised condition.

LS

Yes, sure. But as I had great respect for the Dutch, I lost respect for democracy in Holland.

PL

To return to the question we had before about Postmodernism and you said you struggled against Postmodernism, does that mean you lost? Does the Dutch story indicate that that struggle was lost or is there no connection?

LS

I don’t see the link between the two.

PL

I would argue that the sense of certainty, and control associated with the modern architect, and the ambition, is something that has been eroded through Postmodernism.

LS

It is possible, I think. Surely it starts from then, why not.

PL

You were quite critical in your lecture about the idea of ‘common ground’, Chipperfield’s agenda. Can you explain a bit more?

LS

Firstly there isn’t a common ground. Secondly I don’t think that Chipperfield believes that there is one either. But he wanted to try out this theme. He wanted to see how people reacted to it and I think that the way the architects reacted to it was by grouping themselves, hiding themselves by being a part of a group. And I found this very problematic, so for example, Roger Diener who I know very well, he’s an ex-student of mine, didn’t as he usually does, show the work as if it is the work of Diener. He showed it as part of a bigger group and Diener is there but in a way that you can’t actually see it. So I understood this as a kind of defence mechanism if you like. So that is how people reacted to this need to be part of the common ground and I think it is a problem because if you have done a good building and you say: “It’s mine.” There is no problem with that. It’s not a problem whether you sign it or not or you announce that it is yours or not, the problem is what you do; it has to be something of quality.

PL

So there is a defensiveness among architects?

LS

Yes, and the architects have gone this way, it’s a strange way of reacting. There were very few architects who left their names clearly on show. I found it uninteresting.

PL

It is part of a broader cultural misunderstanding about the relationship between the collective and the individual that believes that you can’t have a strong individual and a strong collective?

LS

Exactly.

PL

I believe you need strong individuals to have a strong collective, but today we seem to think you must destroy the individual to recreate the collective.

LS

Yes.

PL

That is a cultural problem. Architecture isn’t always a direct expression of culture.

LS

Yes.

PL

So it is possible to produce work that is outside of this dilemma?

LS

Yes. I think so.

PL

One of the questions yesterday was about modesty. Can you expand on that?

LS

It is a bad adjective! Because without ambition you can’t be an architect. You must have ambition. I don’t like the term modesty. It’s as if you cut something, you don’t resolve something as well as you can in order to keep it modest. Its not a good adjective, I don’t like it.

PL

But it’s a very popular one.

LS

Very, yes, for sure. There are people who are so immodest that they talk about modesty!

PL

What about doubt? You talk about the importance of making mistakes.

LS

Doubt is fundamental. I remember when I was working with Vacchini and we came up against some problems, some things that were difficult to resolve, we didn’t quite know how to do it. We knew that this was quite a critical moment, and we would go and drink Champagne. It was the moment in which the project moved forward. The project is always about getting over obstacles. When we don’t have any obstacles we have to invent them. Because total freedom is the worst form of prison.

SP

I see this a lot today in our contemporary architecture scene. Many architects in Switzerland producing their own rules, defining the boundaries of their engagement. In a way what we are saying then is that they are doing this because there are no real problems. So are there no real problems in the world anymore or are these architects just avoiding the real problems?

LS

There are always problems in the world.

SP

But why do they have to invent these rules?

LS

Because freedom is the worst form of prison for mankind.

SP

In architecture?

LS

In general. If you have to construct a building, a house in the desert. It’s the hardest thing in the world. I prefer a place there, in the chaos of the city. It seems that there are no obstacles. It seems that everything is possible. It’s a false liberty.

SP

But these architects they have a context; they have a political context, they have a genuine context in terms of a place as well, and cities, they work in cities, and yet they still have to devise these rules. More rules.

LS

Yes, its true that most of the time you do have various types of obstacles but there are situations in which you sometimes find yourself when you don’t have obstacles and then you have to invent them.

PL

This world, is it disappointing, less than you expected?

LS

In part, sure, but not completely. I don’t say that the world is shit. But I would say that I don’t like the direction it is going in. If you look at Europe or Italy or Greece today, that which is happening you can’t be indifferent to this. At the beginning I was part of the extreme left. I was more left than the communists. I had frequent meetings with the people who later became leaders the Red Brigade.

PL

Trotskyist?

LS

We decided not to leave work behind, but to continue working as architects and also do politics whereas the Italian Red Brigade leaders decided to stop working and do only politics. And that is what saved us because we were walking on a razor edge. By a millimetre we didn’t turn into Red Brigaders. The son of Feltrinelli (publisher) went to Turin and put bombs under the main electrical supply. And all of Turin was without light. Feltrinelli’s son died doing this. It was a very delicate moment, because for a millimetre we would have equally become extreme in that sense. They were not bandits, they were incredibly sophisticated and knowledgeable intellectuals.

PL

They weren’t nihilists?

LS

No, not nihilists.

PL

So why were they taking this action?

LS

They wanted to have a complete struggle against capitalism, even an armed fight and that’s when we decided not to continue.

PL

It is interesting to see some of the students reacting to the work that you showed, and they said: “Oh it’s like Marinetti.” It’s got that kind of assertive, decisive, aggressive, almost violent in terms of its imposition. Do you identify with some of the work that was produced in that period. Can you talk a little bit about that tradition in terms of pre-war Italian thinking?

LS

Mussolini came out of the Socialist Party, he gave out new work to young poets, writers, architects all new work to do. That’s why his success came about. He seemed like a man of the left at the beginning. Then at a certain point he turned and became totally the opposite, and that’s how fascism started. So there was a kind of equilibrium. At the beginning people didn’t realise that Mussolini was a fascist. They thought he was a leftist.

PL

But the work that comes out of that period is interesting. It suggests there is not really a connection between politics and architecture in that sense.

LS

There are moments in which the two things come together, but when they do come together its possible that art loses its value, for example in painting in particular.

PL

We only have one more question about the problem of urban sprawl. You raised it yesterday several times as a problem, but you didn’t explain why it is a problem.

LS

My advice is that the world is round, the population keeps growing. Man needs to eat, but if we occupy all the surface of the earth there will be nothing to eat. We need to leave parts of the earth for agriculture. We need to limit the size of the cities and leave room for food production. In a way it’s a very medieval solution, but its necessary today because if we continue spreading ourselves on the territory of the earth we won’t be able to survive.

PL

Are you an ecologist?

LS

Well then I would have a problem. I have always been an anti-green. I can’t stand them!

PL

But I am accusing you of being green in your thinking.

LS

It’s true, you are right. In my life I have never cut down a tree, I have never made a building that meant I had to cut down a tree. When I was teaching in Zürich and all the professors had to present their programmes and the students choose or we choose our students, I didn’t quite know what to present, so I gave them a task. I said: “you are walking in the forest and you find this fantastic, beautiful tree. What is your reaction?” I asked them to write this down. There were almost a thousand responses, I went aside and read them. There were all sorts of things like; beauty, nature, birds, and then there were some more scientific ones about providing oxygen, all the natural processes etc. And I went back into the room and said: “you see that door? You all came in here through that door, you should all go out of that door. Because none of you will be architects.” If your initial response in front of a tree is not to cut it you will never be architects, because your initial reaction should be: “ah, wonderful tree. I can make a beautiful floor, a beautiful table, a beautiful chair and so on, a beautiful roof.” That should be your immediate reaction. But then afterwards you can decide: “Do I want to keep this tree or do I not want to keep it?” And my personal reaction has always been not to cut the tree, but my instinctive reaction should be I am an architect, I need to cut this tree and use it. For me it is a fundamental concept. For this I like very much the aphorism of Paulo Mendes: “Nature is a piece of shit.” In this Mendes explains his aphorism and says that nature is the biggest gift anyone can give us. Nature advises us, and says: “please change me. Change me because my nature is not made for you. And if you change me you always have to fight against me, not with me.” I like this a lot. It is in a sense the foundation of all my work. Even if you build a house in a field you have to destroy something, even if it is just taking out a layer of forty centimetres to make the foundations. So you are cutting the most important part, where you can grow carrots and potatoes and so on. If the person who is designing the house thinks that he cannot replace the value of the land which can grow things that have a value, potatoes and carrots and so on, if he doesn’t think he can replace this with another value, in this case architecture, then he should put down his pencil and not become an architect. This is the responsibility of the architect to replace the value of the land. Because whether we want to not, we are destroying. So we need to replace the destruction that we make.

PL

A lot of contemporary architecture is trying to pretend that it is not doing that.

LS

Yes.