DAVID KLEMMER

︎︎︎Samuel Penn

SP

Thank you for taking the time to speak with me. Your work is immediately recognisable—precise, consistent, and shaped by a strong internal logic. While it doesn’t rely on overt references, it seems to position itself within a broader architectural discourse—echoing certain typologies, formal languages, and sensibilities. With that in mind, I’d like to begin with the idea of inheritance—not simply in terms of style or influence, but as a form of critical engagement. What architectural attitudes or practices do you feel you’ve inherited from your teachers or early education, and how do they continue to shape your work?

DK

The topic of

inheritance feels particularly significant to me. Before studying architecture,

I had considered Industrial Design and Music—disciplines that seemed to involve

a certain rigour and structure. I sensed that architecture might bring those

sensibilities together. But during my studies, I didn’t find a particular

professor or department that shaped my direction. I developed my interest

largely through self-initiated work. The person who had the greatest impact

wasn’t a professor but a lecturer—Till Lensing, a German architect. I took his

course on Tendenza, the Italian-Swiss movement involving architects like Livio

Vacchini, Galfetti, and Botta. That was a turning point. Until then, my

education and approach had felt vague and unfocused. Meeting him and studying

the rational, structural projects from that period opened a door. I began to

sense something I now call resonance—an intuitive connection with the work.

SP

Is that something you’ve continued to rely on—this sense of resonance?

DK

Yes, even if you

don’t fully understand it, you can feel it when it’s there. It was the key to

understanding order in architectural work, how to prioritize and structure

things. This realization led me to discover architects like Louis Kahn and

Valerio Olgiati, whose work had a similar impact on me. From that moment, my

approach to architecture—and my projects—shifted. While at university,

I began crafting what I call an architectural autobiography, a personal record

of pivotal moments of my life that influenced and shaped my work. Some of these

moments came before I formally studied architecture. For example, as a child, I

often crossed a newly built bridge designed by Meili and Peter, with

engineering by Jürg Conzett (Figure 1). At the time, I didn’t know anything

about architecture, but I could sense there was something special about that structure, and it

left an impression. Later, through Lensing and my exposure to Swiss architects

like Herzog and de Meuron, I began to understand architecture not just as a

collection of individual buildings, but as a larger field of shared ideas and

practices. That’s when I became interested in autobiographies of

architects—understanding how their personal experiences shaped their work.`

Figure 1. Footbridge over the River Murau, Steiermark, Austria, by Marcel Meili, Markus Peter, and Astrid Staufer, with Jürg Conzett, 1993–95. © Heinrich Helfenstein.

SP

I remember when Herzog and de Meuron were more theoretical, especially early on. Did their thinking influence you more than the work itself?

DK

It was both. What

fascinated me about Herzog & de Meuron, especially in their early works,

was how they approached each project with the same care and attention as an art

piece. Their collaboration with many artists and the way each project was numbered,

titled, and surrounded by an artistic aura felt mysterious. Beyond that, I was drawn to the

ephemeral qualities of their architecture—the ability to create something

atmospheric, not just tangible. For example, they began experimenting with

olfactory objects—fragrances or perfumes designed to evoke memories of places

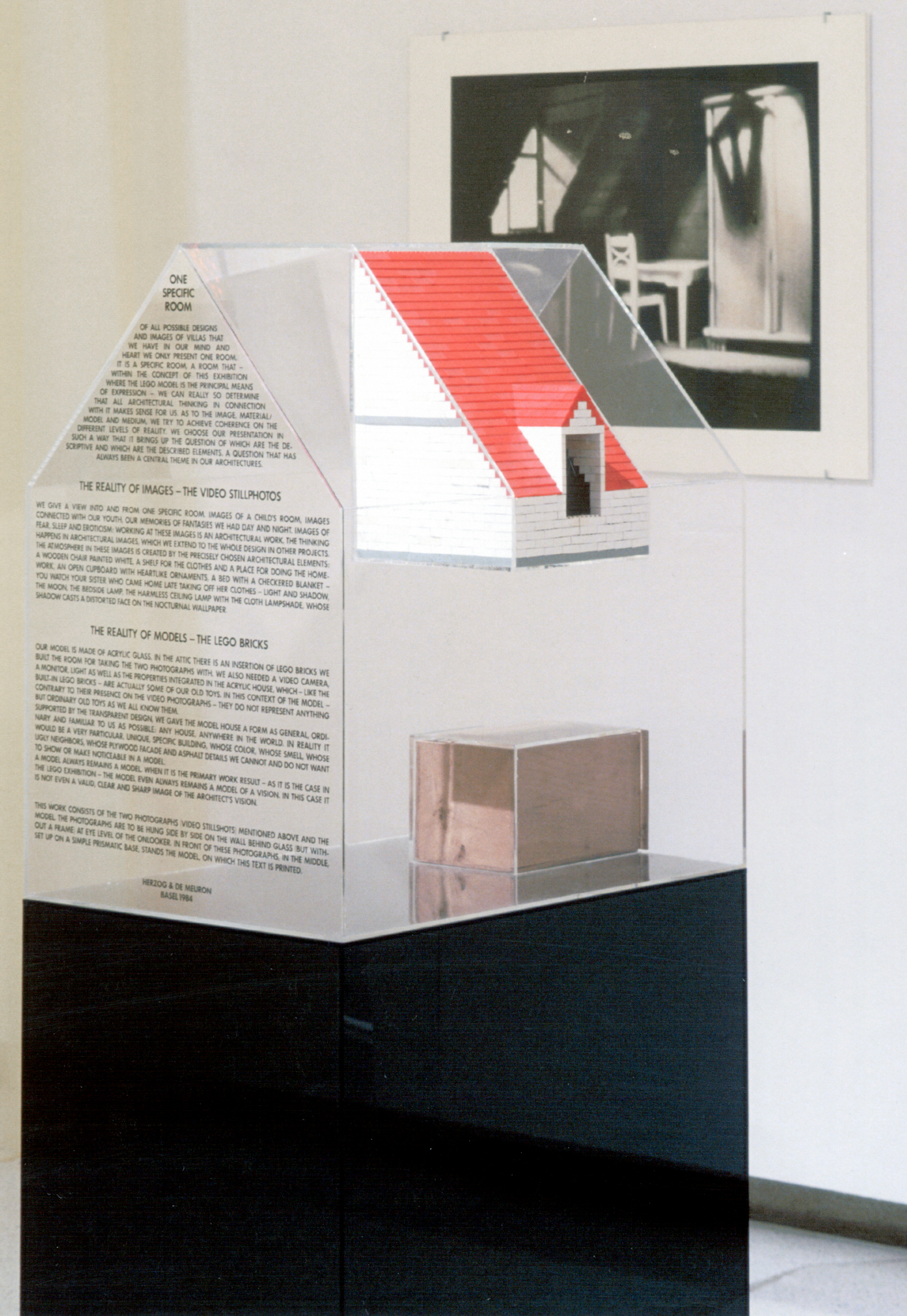

through scent. One project of theirs that resonates particularly with me is

PROJECT 028 – One Specific Room (Lego House) (Figure 2). It encapsulates many

of the ideas we’re discussing—reality, imagination, innocence, and dreams. It’s

playful yet profound, demonstrating how architecture can merge these elements.

The project taps into the concept of architecture as both a game and a

reflection of desire and reality. There is a beautiful text printed on the plexiglass

side, which powerfully speaks to the relationship between the real and the

imagined. I’ve always been fascinated by oppositions in architecture. In my own

projects, I think about light and dark, hot and cold, open and closed, narrow

and wide. These are qualities that, as human beings, we instinctively relate

to, regardless of cultural, educational, or generational differences. When

architecture engages with these elements, I believe it resonates with something

timeless or eternal.

SP

Architecture has a long tradition of treating the project as a theoretical construct. How did the idea of developing your own conceptual studies first take shape?

DK

In fact, during my

studies, I realised that I wanted to explore certain ideas and typologies

independently. To do this, I began treating myself as a kind of academic

client—setting myself briefs, often prompted by a vacant plot, a spatial

concept, or a structural curiosity. Over time, I’ve initiated around 50 of

these projects—some remain purely conceptual, others I return to and revise.

Instead of documenting theories or accumulating references, I constructed a

personal referencing system grounded in recurring questions: how to approach

structure and space, how draw the edge of a roof, how to precisely fix a

window. Whenever something captures my interest, I start sketching a project

around it. Most remain incomplete—some merge, others fade—but occasionally they

materialise into finished works. This evolving archive becomes a mental

framework I draw on when working on competitions or commissions. It’s a system

in constant flux, and it shapes how I start and develop projects. I call them

work-pieces.

Figure 2. 028 Lego

House: One Specific Room, contribution to the exhibition L’architecture est un

jeu… magnifique, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1985. © Herzog & de Meuron.

Figure 2. 028 Lego

House: One Specific Room, contribution to the exhibition L’architecture est un

jeu… magnifique, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1985. © Herzog & de Meuron.

SP

It's a very

compelling process, but don't you find it a bit inward-looking?

SP

It's a very

compelling process, but don't you find it a bit inward-looking?

DK

I do. This approach

is personal. I’m not claiming it’s the right or wrong way—it’s simply what

works for me. Of course, there’s the reality of daily life—competitions, the

building industry, regulations, and norms. But my personal projects are an

introverted space where I can be alone with my thoughts, working through ideas

that help me understand myself. For an architect, it’s crucial to be aware of

your strengths, limitations, and preferences. This space of self-exploration

shapes how I think and how I work. A building may remain unbuilt, or a project

may exist only as an idea, but that doesn’t make it any less significant or

fascinating. In fact, it’s often the opposite—the process of exploring these

ideas always leaves me with a sense of mystery. I don’t consider this practice

necessary, but it’s incredibly helpful. Many of the issues and challenges you

face in competitions can be anticipated, or at least explored, through this

process. It lets me engage with a much broader field of architecture than daily

practice would allow. That’s what I enjoy about it.

SP

It’s almost like an athlete trying to beat a personal best.

DK

Exactly. As an

athlete, you’re not just competing—you spend a significant amount of time

training alone, honing your skills, and developing both your physical abilities

and mental focus. It’s a fitting metaphor for the approach I take with these

projects. This ties back to my encounter with Till Lensing, who started

designing imaginary houses to explore spatial and structural concepts. As I

created images for these projects, I realized that all the houses shared common

themes. It also relates to Kazuo Shinohara’s work, where each project delves

into a distinct spatial experience. His work is carefully archived and curated,

with enigmatic titles, detailed texts, and precise plans, even for his later

unbuilt projects in the fourth style. This is where much of my mindset

originates—from a fascination with unrealized, yet meticulously curated works.

SP

Unbuilt works have

always fascinated me too.

SP

Unbuilt works have

always fascinated me too.

DK

But more recently,

I’ve tried to move away from a rigid architectural system toward something more

open and flexible.

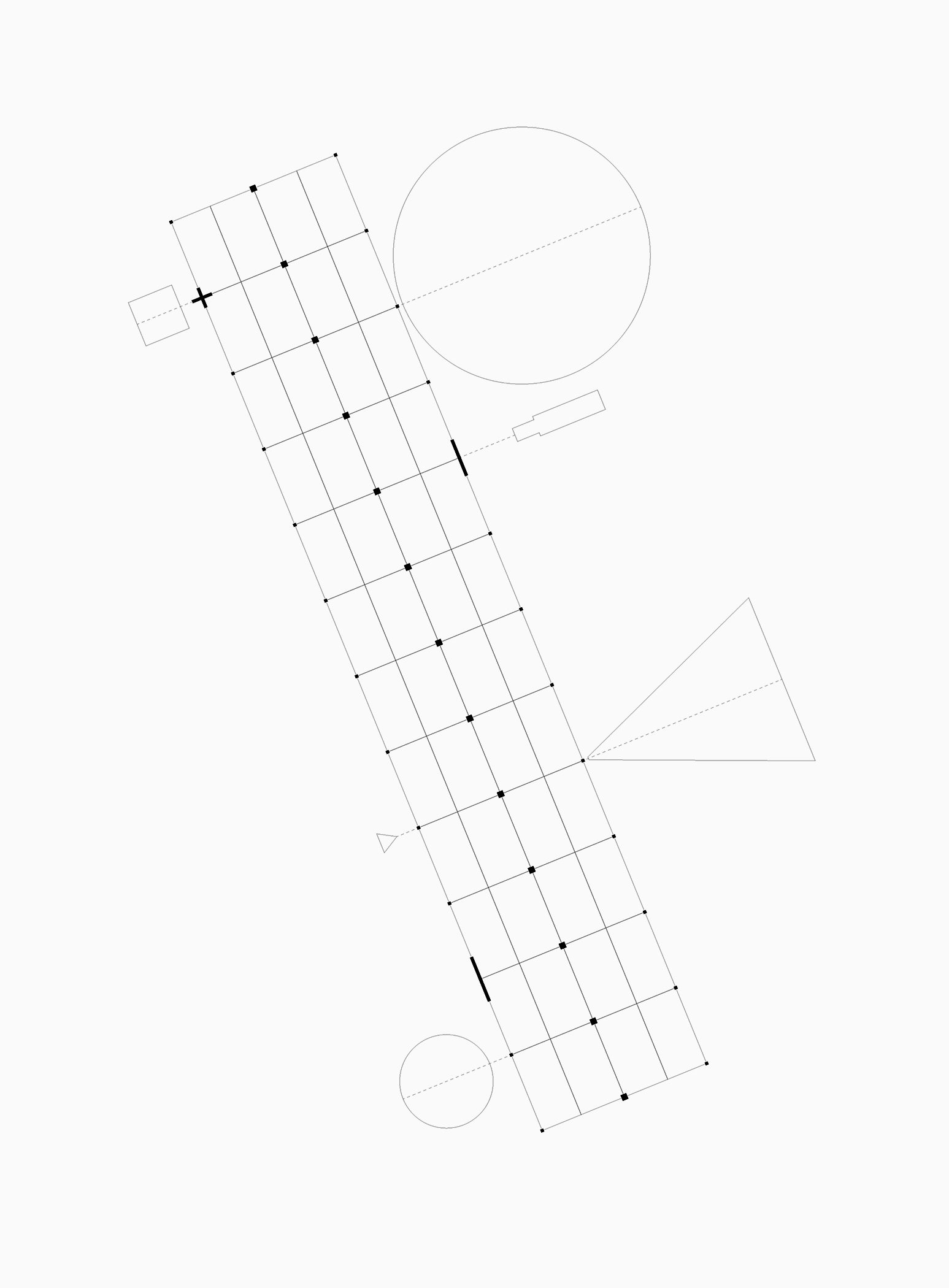

Figure 3. Main floor

plan of the Palestra Polivalente by Livio Vacchini, 1995–97. © Studio Vacchini.

Figure 3. Main floor

plan of the Palestra Polivalente by Livio Vacchini, 1995–97. © Studio Vacchini.SP

So, you’re in a pivotal moment?

DK

It seems so, yes. In

the past two or three years, I’ve experienced a shift—developing a growing

fascination with architecture that isn’t focused on a refined object but

instead feels more incomplete or fragmented. This has ties to my past as well.

I studied in Graz during a time when the influence of the Graz School of

Architecture was still present. The movement, though already fading, left its

mark on the professors teaching there. At the time, I wasn’t particularly aware of it, but

recently, after revisiting the city and these projects, I’ve rediscovered that

period and recognised qualities I had previously overlooked. Examples of such

works include those by Günther Domenig, Manfred Partl, Volker Giencke, Klaus

Kada, Raimund Abraham and many others. They hold attributes that, for me, feel

relevant once more. This interest also opened my mind to architects like Carlo Scarpa, John

Lautner, and Sverre Fehn. These architects, once on the periphery of my

thinking, have now emerged as a significant source of inspiration.

SP

It’s interesting how those earlier periods continue to influence our thinking.

DK

Yes, I’ve been

reflecting on that. I feel a strong connection to the 90s—probably because it

was when I was becoming more aware of the world. When I think back to the

architecture of that time—Kazuyo Sejima, Peter Märkli, Rem Koolhaas—I recognise

something that feels familiar. Maybe it’s just that these architects were

prominent during that period, but I think it also has to do with a kind of

parallel development. I was growing and figuring things out at the same time

their work was emerging, and it creates this strange sense of alignment.

SP

A kind of synchronicity?

DK

Yes, that’s probably

why I find myself looking back now. I think there’s a sense—whether real or

imagined—that things were more open then. Architecture seemed to allow for more

experimentation, less pressure to conform. I sometimes feel nostalgic for that—not

to recreate it, but to ask what can be carried forward. Another part of it was

the arrival of digital tools. In the early 2000s, when the internet became

widely accessible and home computers were more common, it felt like a shift. A

transition between analogue and digital ways of working. I experienced that

change quite directly.

SP

Did those tools change the way you thought about working?

DK

Definitely. The computer became my tool. It

introduced a level of precision that was completely new—suddenly you could

control everything with exactness: line weights, spacing, the structure of a

drawing. That kind of refinement became part of how I understood clarity in

architecture. I think of someone like Livio Vacchini, who was deeply engaged

with what computers made possible. He developed drawings that were

computational and rational, but still expressive (Figure 3).

Did those tools change the way you thought about working?

Figure 4. Digital Negatives, David Klemmer, 2024.

SP

And in this context, representation becomes crucial, especially when you’re not building—the way you represent your work can influence how it’s understood.

DK

Yes, for young

architects, or those not building much, representation becomes increasingly

crucial. It’s about perception. A simple change in line weight can entirely

alter how a floor plan is read. Representation not only clarifies a project but

also shapes how it’s mentally interpreted. For unrealised works, representation

essentially becomes the project itself. When I was working on my diploma

project, this was a critical part of my process—understanding what a plan, a

text, a title, or an isometric drawing should convey, and how each discipline

illustrates a distinct aspect of a project. A plan offers a different reading

than a text, a physical model allows for interaction, a photograph captures

atmosphere, and so on. This is particularly relevant in the context of digital

renders. I’ve been working on a series called digital negatives (Figure 4),

which I approach as a way of leveraging the unique capabilities of the

computer. Initially, I rendered them in perspective, but I later switched to

isometric views, as this projection is something you can’t capture with

photography. The inversion of colour evokes a connection to the aesthetics of

analogue films. Both decisions cause the simple generated images to appear at

once familiar and unfamiliar, with the readable space and the structure of the

projects standing out distinctly.

SP

What about three-dimensional visualisations—spatial models, for instance—what do they offer that other forms of representation don't?

DK

With real-time

computing, we can experience virtual space from the outset, making it an

efficient tool for exploring spatial concepts that physical models can’t match,

especially in terms of speed and precision. It’s also a flexible tool for

researching and modifying projects—allowing easy adjustments or deletions. I

don’t see it as competing with other architectural tools; rather, I view the

digital realm as an additional instrument in the development process. The

digital world offers a fascinating juxtaposition to the physical world. A few

years ago, I began noticing a resemblance between the blackness of outer space

and the blank computational space of 3D programs. They're quite similar—both

allow things to exist and rotate without the constraints of gravity. In the

digital realm, we can achieve things that aren’t possible in the real world,

and that’s what makes it so captivating. When discussing oppositions, we must

recognise that our awareness of balance stems from knowing the extremes. The

extremes help us appreciate the middle ground, and that holds true for the

digital world as well. It offers possibilities that are completely opposed to

the real world’s limitations, though there’s always an effort to merge the two.

It’s a complex relationship.

Figure

5. Microprocessor 80960JA, Intel, 1990.

Figure

5. Microprocessor 80960JA, Intel, 1990.

SP

What I’m getting at

is that the real world is chaotic—full of uncertainty, failure, and

compromise—whereas the digital allows total control. That pull toward order is

understandable. But even in your digital work, you stay grounded in structure,

gravity, and physical logic. So, I wonder if you would be uncomfortable

producing projects that were purely fantastical or non-physical?

DK

While we strive for

order and stability in the real world, the digital space requires a hint of

imperfection and error to feel relatable. My focus on the digital realm aligns

with my deep-rooted interest in realism. Even as a child, I was drawn to

it—never using colourful bricks when constructing Lego houses, always imagining

how toys like cars and planes would function in the real world. My passion for

model-making, building railways, ships, and cars with a focus on scale and

accuracy, has stayed with me. Even today, I view the world attentively and with interest. It is

important to train the eye. However, this grounding in realism also allows me

to appreciate objects that challenge traditional notions of visual design.

Take, for instance, the microchip—a fascinating object because, although it is

usually hidden, its design is surprisingly beautiful and complex (Figure 5).

The way its connections are laid out creates a visible, almost architectural

pattern. To me, the microchip is the heart of everything, powering all the

digital processes I work with. There’s something intriguing about this small

object, which reminds me of satellites or space modules—there’s no aesthetic

decision or visual design, just the result of a system’s logic. It’s this

precision and function that I find compelling, and I look for similar ways to

integrate functional elements into my architectural work.

What I’m getting at is that the real world is chaotic—full of uncertainty, failure, and compromise—whereas the digital allows total control. That pull toward order is understandable. But even in your digital work, you stay grounded in structure, gravity, and physical logic. So, I wonder if you would be uncomfortable producing projects that were purely fantastical or non-physical?

Figure 6. International Space Station (ISS), 2021. © NASA

SP

You often reference space-age technology, like satellites and scientific instruments, on your website and in your projects. Where does that come from?

DK

Satellites and

instruments captivate me, especially when it comes to exploring how they are

assembled. For example, the International Space Station (Figure 6) is entirely

functional—there are no aesthetic choices. It's equipped with sensors, solar

panels, and other components carefully integrated into the main structure. In

my projects, I strive to create a similarly efficient system, where elements

like staircases, roofs, chimneys, or technical components are integrated but

retain their distinct appearance. A good example is the Lido Bruggerhorn

project (Figure 7), where certain elements contribute to the sense of assembly,

enhancing the expression of the project. I frequently join parts using a

hinge—it’s a wonderful component that separates and connects a static and a

dynamic element. Visually, it alludes to movement and function. This technical

curiosity also connects to my interest in industrial design. I think the

comparison between machines and instruments is interesting here. The beauty of

an instrument lies in its technical necessity and precision, but also in how it

allows for human interaction. The way we touch and engage with it—the sizing of

elements, how it reacts to an individual. The performance it generates needs to

be precise, but at the same time, it has to be adaptable, allowing me to

interact with it. The Polar Planimeter Type 7 (Figure 8), for instance, relies

on you to guide it—it becomes an extension of the body. That closeness is

something I find very beautiful. In architecture, there are comparable

moments—doors, handles, windows, railings—objects we interact with every day.

They’re not just there; they ask something of us. In that sense, a house can be

understood as an instrument for daily life. A machine, on the other hand, is

designed to run on its own—you press a button, and it performs its task without

you.

...

Figure 8. Polar

Planimeter Type 7, Alfred J. Amsler & Co., 1918. © Mathematical

Instruments.

Figure 8. Polar

Planimeter Type 7, Alfred J. Amsler & Co., 1918. © Mathematical

Instruments.