Hadspen Pavilion II 2008 Credit David Grandorge

DAVID GRANDORGE

︎︎︎Kieran Hawkins

The following are excerpts from a conversion between David

Grandorge and Kieran Hawkins in November 2023.

KH

How would you articulate a relationship with the past in your work – with inheritance and disinheritance?

DG

There is a personal history, the development of knowledge of

architectural history and also the histories of art, photography (especially as

an artistic practice), literature, humans, geology, ecology, non-human animals

and also many smaller things. The personal history is important. Maybe we’ll

discuss some of it later.

The writers who have been important to my thinking about

architecture and photography include: Robin Evans, Paul Shepheard, David

Leatherbarrow, Georges Perec, Primo Levi, Geoff Dyer, Yuval Noah Harari, James Lovelock, Teju Cole, Susan Sontag, Walter Benjamin, Stewart Brand and many

more.

I have no favourite architect, or movement of architecture,

but there are buildings important to me because they provoked a strong emotional or

intellectual response when I encountered them. They include:

- Pantheon: Rome, 126 AD, Unknown

- Wren Library: Cambridge, 1695, Christopher Wren

- Soane Museum: London, 1824, John Soane

- Schindler

House: LA, 1922, R.M.

Schindler

- Villa Muller: Prague, 1930, Adolf Loos

- La Tourette: Eveux, 1961, Le Corbusier

- Upper Lawn Pavilion: Wiltshire, 1962, Alison & Peter Smithson

- Danzinger Studio: LA, 1964, Frank Gehry

- Salk

Institute: La Jolla,

1965, Louis Kahn

- Leca da

Palmeira: Porto, 1966,

Alvaro Siza Viera

- Gehry House: LA, 1978, Frank Gehry

- Spiller House: LA, 1980, Frank Gehry

- Lisson Gallery: London, 1992, Tony Fretton

- Van Hee House: Ghent, 1997, Marie-Jose Van Hee

- Santa

Maria do Bouro: Amares,

1997, Eduardo Souto de Moura

- Svartlamoen

Housing: Trondheim,

2005, Brendeland & Kristoffersen

- Row

Houses: Svalbard, 2007,

Brendeland & Kristoffersen

- Raven Row: London, 2009, 6a

- Tour Bois le

Pretre: Paris, 2010, Lacaton

& Vassal

- Tree House: London, 2013, 6a

- Teller Studio: London, 2016, 6a

- Feilden Fowles Office: London, 2016, Feilden Fowles

- Cork House: Eton, 2019, Matthew Barnett Howland

- House for Artists: London, 2021, Apparata

There are many other buildings that I have been influenced

by, but not encountered. I would like one day to visit some of them, to

experience their spaces and external form and also to see how they have

survived the vicissitudes of time.

KH

What inheritance do you hope to pass on through your practice?

DG

The disciplines I

practice at this moment are teaching, photography (in many guises), writing

(that I am both good at and not good at), making buildings with timber with my

own and other hands and looking after the needs of others as often as I can,

especially the homeless. I hope only now, in most of the work I do, to

encourage others. Is this an inheritance?

KH

What were your core interests when you started your work as an architect, teacher and photographer? How have these interests evolved and influenced each other over the years?

DG

I had no core

interests. I was interested in and practiced many things when I left college. I

have developed a set of reasonably clear intentions in most of my work over

time - a thesis by accretion.

Upper Lawn Pavilion, Alison & Peter Smithson

Upper Lawn Pavilion, Alison & Peter Smithson Credit David Grandorge

KH

One of the things that I thought was interesting in your first answer, was that you chose to list writers rather than books, but you chose to list buildings rather than architects. Is there a particular reason for that difference?

DG

Architecture has many authors. Writers most often work

alone. They can be tyrannical. An architect should not be. A writer’s output is

democratic. Buildings should also be. Architecture without writing would be a

sad state of affairs, wouldn't it? Architecture needs to be theorized,

abstracted, critiqued and re-understood. Good writers are able to articulate

things about buildings that their designers didn't intend.

A mature architect, I think, doesn't worry too much about

criticism.

What's interesting about writing is that it can be sustained

over a longer period. Good writing is autonomous. Architecture wants to be

autonomous but will always struggle to be.

Thinking about recent history, there are many things that

prevent architecture being practiced as well as it could or should be. There

has been a loss of agency for architects: in planning terms, in terms of a

construction industry that doesn't really play fair, against all sorts of

external forces that have affected supply chains: we have experienced a

pandemic, there are now wars in Ukraine and the Middle East and the UK has

exited from the EU. You add up all those things and realize how it has made

good architecture much more difficult to realise.

The amount of architecture per square foot in the early

buildings by an architect is usually very high. If you look at many of the

projects listed, they were the earlier work of an architect, and this issue of

inheritance and disinheritance is interesting in relationship to this. I do not

disinherit their later work though. There is always the issue of how an

architect is able to move up in scale and keep the same architectural intensity

when there are so many things that can prevent this happening.

KH

To come back to the analogy with writing, in many ways the architecture becomes more dilute, as an architect goes through their career, as other factors come in.

DG

That’s sadly true but it's not always the case. There

are architects that transcend this condition. Siza would be a good example.

KH

Yes, but with writers it is more often the inverse.

DG

I've really enjoyed reading books by the writers listed.

I'm interested in the consistency of their voice, whatever subject is being

addressed. I'm not so much interested in the architect's voice or their

insistence on the importance of their authorship. Maybe architects have to

assert their authorship in order to stand up to all the stuff they have to deal

with on an everyday basis. They should also strive to be modest.

We are facing new challenges, particularly that of

mitigating climatic damage. I'm interested in what and how we build in the

future. Even though I sometimes feel challenged about teaching in a school of

architecture with my ecological concerns, I still get a lot of joy from

experiencing buildings, from seeing care, gentle innovations, a sense of

generosity and sometimes a clarity of ideas and execution. These things form

part of my teaching.

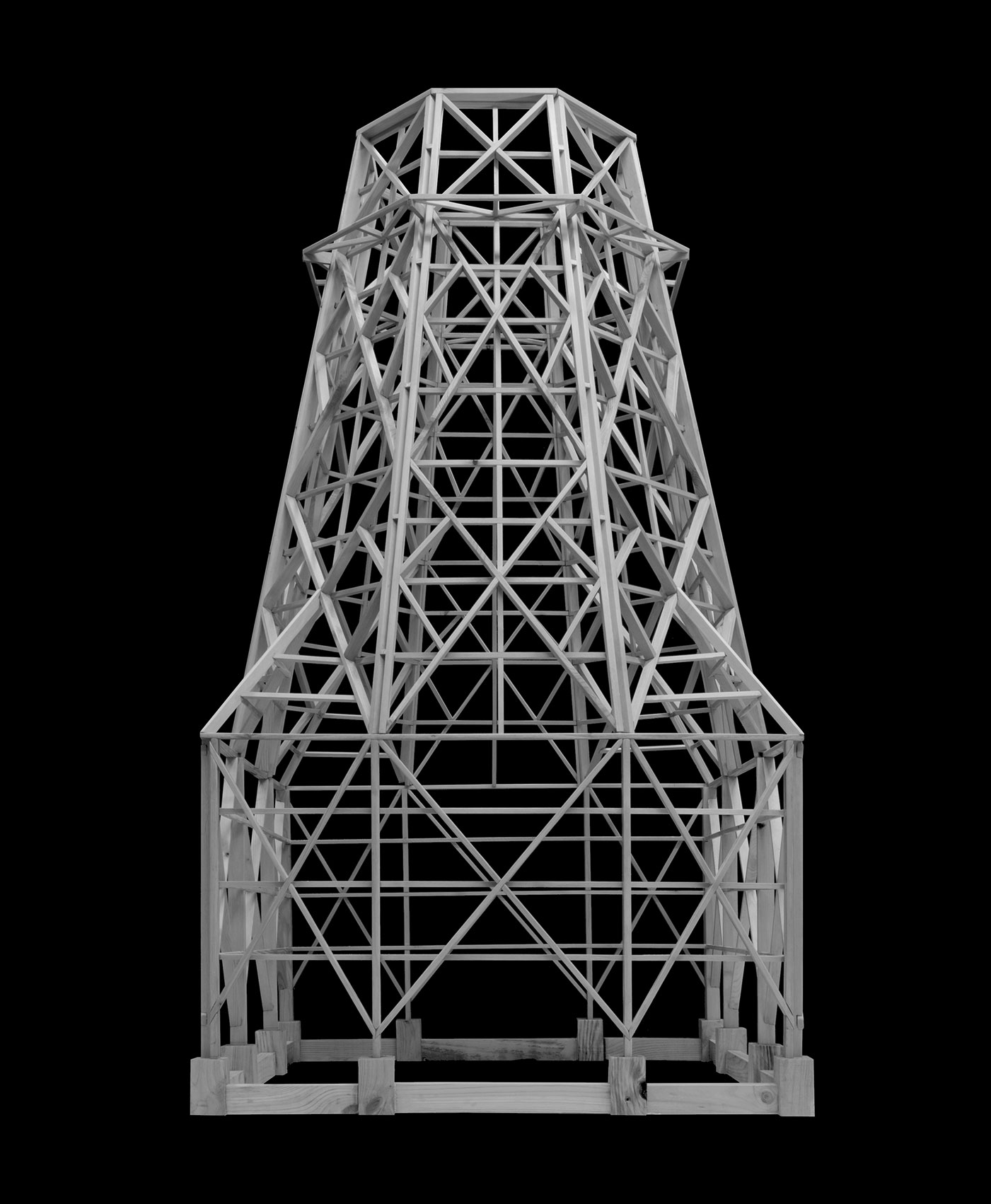

I do enjoy a certain

austerity in buildings, but also spaces in which the idea of pleasure is

evident. Although I have no religion, I am still fascinated by churches, from

the smallest chapel to the tallest cathedral. I feel exactly the same way about

the inside of a cooling tower. It does the same thing as the Pantheon, that

mediation between sky and ground is so powerful. When spaces are top lit, and

you have less reference to the outside world, it’s almost primeval. It’s about

being in the cave, having darkness and looking out to the world.

Cooling Tower, Timber Translation 2017 Credit George Fenton,

Kai Majithia, Tarn Philipp

KH

I think there can be something about being in a church or a place of worship that is lonely, and quite vulnerable. That intensifies the spatial experience.

DG

Is it that first encounter or is it something that works

on you after having been in there for a time when your eyes adjust and you can

pick out details? Some buildings need quite a lot of time to experience and to

understand what’s going on. Or even going back to spaces at different times of

day when the light has changed.

I suppose my epiphany was when I was in the Pantheon and it

rained. That was such a beautiful experience. The rain fell in a diffused top

light, and the filigree of that rain against the coffers. Wow. Then was the

sound as well and the movement of water into the drain at the centre. It’s such

a perfect piece of architecture. The experience was collective, but probably a

little different for everyone.

If we're talking about the inheritance from this, it was at

first to be moved by space, light and materials in quite a simple and direct

way and then moving on, through reading and practice, to a growth in my

interest in first tectonics, then embodied energy and finally an understanding

of life cycles. This building has lasted a long time. It communicates to its

contemporary inhabitants, I imagine, in a very similar way to it did to those

who lived two millennia ago.

What is interesting about Barnabas Calder's book

(Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency) is the way he looks at

architecture in terms of the energy a society uses to make its buildings and

infrastructure. He argues that form follows fuel, but he is still moved by the

achievements of architecture. Sometimes humans do impressive things.

I think that a really important inheritance for anyone

starting the profession is to be moved by architecture, otherwise why study it?

I don't like to sound naïve. It's not all about emotion.

Practice requires a keen intelligence and also an inner strength to manage

inevitable disappointments along the way. If designs are good and they are well

developed tectonically, spatially, highly calibrated, and then a client doesn't

get it or there is not enough money, or the planners don't like it, sometimes

it's a war of attrition to keep the building in the state that it was

conceived. Sometimes it's a little more gentle, sometimes it's a retreat, there

are battles you just can't win.

Tour Bois Le Ptetre I 2013, Lacaton & Vassal

Credit David Grandorge

KH

Coming back to your list of buildings; I appreciate that you've chosen to list buildings rather than architects, because it brings to mind direct experience as the heart of your thinking about architecture.

DG

Sometimes it's experiencing but sometimes it something

more, a duty to bear witness. This has involved making quite painstaking visual

records of buildings, cities and landscapes with strong intentions about how

their qualities can be mediated. That's not in all cases.

KH

Have you also taken photographs of all of them?

DG

I've experienced all of them. With the Pantheon, my

partner and I knew we would be becoming parents of twins in a few months and

this was our last chance, or first chance, to go to Rome. I chose not to take a

big camera. I did take a few snaps but I wasn't there to document the city. We

really wanted to experience the city in an unmediated way.

I’ve been privileged to be inside Trinity Library a few

times. A postgraduate student from Trinity College helped me to get access out

of hours. I often ate my usually sparse evening meal on the banks of the river

Cam looking at the library with the west light on it. I did this many times.

I've always been intrigued by the story of the building and also this amazing

period in Britain where for the last time we had a group of people who were

thinking outside of the academy and there were some incredible innovations by

Wren, Hooke and Boyle. I think that the library does it for me more than St

Paul's because of the clarity of its spatial order and tectonic.

KH

There’s also less cultural baggage than St Paul’s.

DG

I agree. But it’s also about what it gives back to

Neville’s Court. What it does on both sides is very powerful. As it is largely

open on the ground floor, there is a direct visual connection from the

courtyard to the landscape to the west. I love the fact that this library full

of important books, including some of Wittgenstein’s notes, was lifted above

the flood plain.

KH

Something I like about that building, not knowing it deeply, is the discontinuity between the façade and the structure

DG

It’s very powerful the way Wren composed the facade. He

deliberately extended the middle section of the elevation. The relationship

between façade and the interior invites a misreading. It’s quite an austere

building for Wren, quite restrained.

When I started studying architecture in 1990, I was already

immersed in the early work of Frank Gehry. I had studied for an A-level in

modern art and architectural history at night school the year before. The

history of modern architecture and painting was already an inheritance.

As a young student, I was aware of stuff happening in

Switzerland and also that there wasn’t much confidence in the profession in the

UK at the time. The Prince of Wales had recently made his point. He had

cancelled the Mies van der Rohe tower on the Number One Poultry site. Stirling

would build there soon afterwards.

It was an interesting period. At postgraduate level there

was a greater awareness of the early work of Herzog and de Meuron, which I

still think is exemplary. We’ve been studying factories in my studio this year.

Students have made model fragments of six exemplary 20th century examples. One

of them is the Ricola Storage Facility by Herzog and de Meuron.

What's interesting is that the architects were given a

prefabricated steel frame shed clad with SIPS panels. It was all set out

already and the client said, look, these dimensions are determined by the

gantry crane to be employed. It enclosed a completely automated storage system

for herbal sweets. The stuff that architects were complaining about in London,

Herzog and de Meuron chose to embrace.

KH

They were given freedom only with the design of the façade.

DG

They had no problem with that. The site was a spent

quarry and they had to clad a building that was nineteen meters high. It was

like, how do you de-scale this big thing. Then they took the idea of stacking

and made this beautifully layered façade with very little waste. It's such a

clear tectonic, incredibly elegant. Nothing about the façade has got anything

to do with the structure inside. In fact, it's a completely different grain and

that doesn't matter.

This is a very different way of thinking about architecture

and it can be done well, as in say, the Ricola building. Or it can be done....

KH

Like a Holiday Inn.

DG

Absolutely.

KH

I think there's something about architects having an idea to believe in, that I'm thinking about with religious buildings. Modernism offered that too, at the beginning.

DG

A good factory is like a church, by the way.

KH

Yes. Architects believing in what they're doing and doing it with commitment and care, which I think early modernism had.

DG

But early modernism wasn't nuanced. It was declarative.

It was evangelistic in many ways. Architects had good reasons to think like

that. They'd just been through World War I and they wanted to remake the world

anew because of World War II, because of the advent of bombing by planes and

the destruction of whole swathes of cities. This is the context that modern

architects operated in, and what they did, and what they believed in, did

transform our world.

But there was a lack of thinking about the relationship

between nature and culture. The evangelism of modernism led to a divorce

between thoughts about the natural world and architecture. After World War II,

circular ideas were prevalent. Look at the reclamation of brickwork in Berlin.

It was a process undertaken with an improvised plan and with very little fuel

for the workers, who were mainly women forming chains. These things still

happen in the world, which I find absolutely fascinating. It's about finding

the right size materials and people working collectively for a public good.

That's an interesting idea.

I think that was talked about a bit by you at the Poetic

Pragmatism symposium last year. Like you, I'm interested in making going back

to being undertaken by many hands. Some of the impetus for this has come from

Steve Webb, but also from Tom Emerson. Those incredibly fresh early projects

when he started teaching at ETH. The first project was called 96 Hands. It was

undertaken with forty-eight students. To deal with health and safety issues,

the students were not allowed to use any power tools. The project addressed

circularity before it was called such a thing.

Frank Gehry’s on the list, his earlier works. The thing that

I was interested in at that time was the loose-fit way in which he explored the

possibilities of timber frame construction. He did lots of different things. He

played with geometries as well. I liked that. It’s simple trigonometry. It’s

quite simple maths to use. There are compound angles, which is just like doing

a hipped roof. I really love the way he allowed the balloon frame to explode

and that it had something in common with brutalism, the very direct use of

construction, much of it left exposed. You don’t have to add lots of layers.

It’s about what you take away.

Gehry House I 1999, Frank Gehry

Credit David Grandorge

KH

A bare rawness.

DG

Yes, it's raw, which is very powerful. There's also this

idea of something being definitively unfinished. Later on, through Tom Emerson

and Irene Scalbert, I came to learn about bricolage as an architectural

strategy. It's there in Gehry’s work. The poetic pragmatist is a close

relative.

The bricoleur is able to respond quickly to tricky

situations. I've been amazed by speaking with architects during a period of

material shortages, how they have found other resources closer to hand. I think

that swiftness in the ability of architecture to adapt to rapidly changing

situations is a very important issue at this moment in time.

The bricoleur is also interested in multiple stimuli. I

think that sensibility was there in the early work of Herzog and de Meuron.

Another early influence was my studio teacher in my fourth

year, Peter Beard. A lot of people have been talking about the introduction of

ecology into the architectural education curriculum. This was happening back

then in 1994. I was encouraged to design a water collection system, the water

collected from the redundant Thyssen factory roofs. The water would be fed to

the garden through an irrigation system, a garden that would test the

resilience of European plants in technogenic soils that were found in the

ground outside of the blast furnaces. Peter introduced me to a set of ideas I

hardly understood at the time.

It was only about ten years later that I really got to grips

with what he had taught and why it was important. Sometimes it takes time for

an inheritance to be received.

KH

Which connects very much to making do with what's there, with a creative, incisive decision-making.

DG

There was a gantry crane that was used to drop a very

heavy ball onto steel to break it down into smaller pieces before it would go

back to the blast furnace. The steel frame that held up the gantry crane, you

could see it'd been bashed in parts, and some of it was rusting, especially at

the top. It was proposed that the steel structure be dismantled, and that

certain sections of it would be cut and stress-tested. I now recognise that

there was quite a lot of redundancy in the repurposed elements used.

As the earth in the existing hole had had such great force

dropped upon it, Peter persuaded me that the compacted earth might have the

properties of a rammed earth floor or stronger. There would be no need for a

foundation. The steel frame structure would be dropped in the hole in

prefabricated sections. The overall form was like a skeletal eggcup. The steel

frame held a fibreglass water tank that would be walked around on the journey

to the platform above that overlooked the garden.

There are many conversations now about circularity and the

use of material passports. Thirty years ago, this ecological conversation was

evident in some of the teaching at Cambridge. I was encouraged to look at

Linnaeus, and I really got into the idea of cataloguing.

I went to the botanical garden, and met a very old professor

of Botany who seemed to be quite taken by me. I was wearing overalls and had a

shaved head, not a typical look for a Cambridge student at the time. He spent

two hours with me, explaining everything they did there, including one of the

most beautiful experiments I've ever seen, a timber A-frame of bamboo

suspending fluorescent lights over these quite innocuous looking garden

flowers. I asked, “What are you doing?” He said, “We’re testing which British

flowers would survive two degrees of climate change.” I loved the directness

and simplicity of the experiment. I don’t know if the method was rigorous, but

it appeared to be so at the time.

When I was in the Arctic in 2007, I documented an antenna

field operated by the Max Planck Institute. There was an array of upright

scaffold poles from which hung really ordinary looking plastic buckets.

Underneath the buckets was some very expensive sensing and recording equipment

that was being use to measure electrical activity in the Ionosphere.

Sometimes I think

architecture could be a little bit more like that, where you can read primary,

secondary and tertiary elements. There could be greater simplicity to the

components we employ. Maybe High Tech tried to do that at its beginnings but it

became too techno-fetishistic. If you look at Team Four, there is an incredible

clarity in how they articulated each building element and their connections.

That's an inheritance, that ability to read a building because of its legible

structure.

Svalbard (Max Planck) I 2007

Credit David Grandorge

KH

In all of the examples that we're talking about, there's an enjoyment in being able to read or understand how things are made.

DG

All of them? Maybe with the exception of the Villa

Muller, but that has other qualities. The Schindler Chase house is pure

tectonic.

I think that’s very interesting, this could be the red

thread. It’s maybe also a transfer of those inheritances and interests.

The other thing I do is photography, lots of it, maybe too

much. I’ve been very lucky with the quality of buildings I’ve been commissioned

to document in my photographic life and I feel grateful for that. Also, I

record many other things, things I’ve chosen to take an effort to go and see.

Mainly, I chance upon situations that I feel are worth documenting.

What’s not on the list is a lot of the more anonymous urban

environments that I have spent quite a lot of time documenting. I particularly

enjoy the experience and the photographic opportunities of the more anonymous

hinterlands of cities.

Apart from photography, a lot of my work has been teaching.

I’ve been teaching architectural design and construction for twenty-eight

years, all the while maintaining some interest in architectural history. Sometimes I’m

interested in absolutely ahistorical analysis.

I am sceptical of the idea of context as it is commonly

understood. I’m not that fond of nostalgia, though I’m prone to it sometimes. I

think context is incredibly important to talk about, but we should relate to

precedents in a more nuanced way.

I think learning about what fails and why this happens is

interesting as well. Some recent writing has addressed this issue. Douglas

Murphy’s book comes to mind.

When we analyse precedents in the studio, we try to be

thorough. We also use precedent to analyse different forms of construction.

We’ve looked more than once at timber translations, translations from stone,

concrete and steel. We are interested in how heavy buildings can be made

lighter and be less carbon intensive.

We’ve explored how different industrial building types could

be made from timber. We’ve even looked at how the Pantheon could be made from

timber. Some of it is about performance issues, but we’re also concerned with

the language of construction. When there is a very direct use of a tectonic

system and material expression, they can combine with the modulation of light

within the space and bring about a strong emotional response.

Take the Cork House. There’s a system evident, but also

lessons learnt from history, from pyramids and corbeling. It goes back to quite

primitive architecture, yet it’s all CNC cut with minute tolerances, all so it

could be friction fitted with no mechanical joints. What’s amazing about the

project is its darkness and its acoustic qualities. I’ve brought many

architects and students to see it and what they have all talked about, after

being told about its low carbon construction and its attitude to life cycle and

so on, is the building’s powerful atmosphere, its quality of light, the

calibration of space. It is architecture of very high level. This was very

important to its designers.

Matthew Barnett Howland (one of its authors) and I have

collaborated together in teaching and discussed many issues over nearly three

decades. We had many conversations during the early stages and construction

phase of the Cork House. His tenacity during the development of the project and

the build was incredible to witness. There was a lot of risk to this project.

Innovation can be scary at times.

KH

What’s come up again and again so far today is a combination of constructional clarity with rich atmospherics.

DG

Maybe that’s all we’ve got, right?

KH

Maybe.

…

Cork House II 2021, Matthew Barnett Howland

Credit David Grandorge

KH

Let's talk about your photographs. I also want to talk about your writing and I wonder if we can talk about them at the same time, because you say that you're writing now, which you claim you are both good at and not good at. I'd like to hear more about that. I was thinking about the way you write and the way you take photos. For me, there are clear parallels between them, and I can hear your voice in both. It's about everyday language; there's an unpretentiousness and at first glance, or first reading, both can appear quite simple but are actually very highly considered and contain a great deal of understanding and sophistication. There's a tautness, a tightness to them. I wonder if this is something that reflects how you see the world, or it's how you want to communicate?

DG

It’s how I want to describe the world. It is informed by

how I see the world, but it’s more about how I want to describe it. I want the

image to be as succinct as possible.

KH

Do you see your writing in the same way?

DG

The writing comes from the same wellspring. In

conversation, I am embarrassingly verbose. I try to be a more precise version

of my verbose self when I write.

I wrote a very prescient dissertation as a student, which my

tutor hated and the external examiner loved. It was called God Loves You.

It addressed the impact of secondary realities on architecture and humanity at

large - the thing we’re going through now from algorithms to AI. The time

people spend glued to their phone was there in all the conversations about

cyberspace at the time. We didn’t know then what the interface would be. I

didn’t know it was going to be the so-called smart phone that would enslave

most of those who use it.

Often, people take photographs because they don’t want to

write. They want to make an image of something because they don’t have the

words to describe it. That sounds like what a painter does. But painters and

photographers can be articulate about what they do and why they do it. But they

will always prefer that someone else write about their work.

I started taking pictures from about 1991 when I met Edward

Woodman, a photographer who worked with the art world. I had direct access to

this world through him, including some very important artists of that era. That

was an inheritance.

KH

Artists such as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst?

DG

Tracey Emin, no. Damien Hirst, yes. Mona Hatoum, Rachel

Whiteread, Helen Chadwick and many others. Tracey Emin did once walk in to one

of the strange pop quiz nights at the Bricklayers Arms in Shoreditch that I put

on with my friend Brian Greathead. Look, a lot of people were around.

KH

What a great time to be in that part of the city. It’s so different today.

DG

We just happened to be around at a good time for the

city. For a while, rent was cheap.

In 1994, I saw an exhibition by Thomas Struth called

Strangers and Friends at the ICA. There was a picture there that transfixed me,

Bernauerstrasse II. It was taken on February the 6th, 1992.

What I was interested in was the way he conferred the same

dignity on his human sitters as he did on the city in his street photographs.

They were empty, but compelling. I liked the light he shot in and the viewpoint

taken that allowed an equality of description between all the elements in the

frame. I liked the way he composed with colour.

This was a way for me into photography. By this time I

already held the Bechers in high regard. I was very interested in this reading

of industrial forms, the issues of typology, repetition, of similarities and

differences, minimalism, of conceptual art. It was all in the air, these

things. Then there was Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff.

When I started out some architects chose to work with me

because I pursued a certain type of photography and we had quite long

conversations before I started taking photographs for them. Some of these

practitioners I still work with.

In 1999, after I had bought my first view camera on a hire

purchase arrangement, I started making independent work in a more sustained

way. It suddenly made sense to record things. I could get the same amount of

information that the Bechers had in their negatives. I had many large format

negatives that I did not scan until about fifteen years afterwards. Sometimes I

made prints. I just had this stuff. I had this archive of negatives, of

history, just sitting there.

KH

It must be amazing to see now. It must be like time travel.

DG

It is. It was pretty rough for me at first. I didn’t

start with money. I’m amazed when young people start with these amazing

cameras. I was hiring equipment for years. It took a while to find my voice.

When I found my voice, I used it.

With the writing, I wrote for the Cambridge Architecture

Research Quarterly. It was a review of a book about the life and work of the

Bechers by Susanne Lange. It was the first time I had to do some disciplined

writing. Footnoted. Analytical.

KH

Yes, serious academic stuff.

DG

Serious stuff. It was a good piece of writing. It took

ages. I had young kids then and I used to go to a mate’s flat to write with a

small bottle of whiskey and packet of cigarettes on the desk beside me. They

were both sadly depleted by the time I had finished writing. My copy of the

book is now completely battered. I’ve used it for reference many times.

Photographic work is different to writing. If they are both

laconic and austere, I hope that there’s also a little bit of wit there

sometimes.

KH

Absolutely.

Auvere I 2016

Credit David Grandorge

DG

One thing I was interested in, when making photographs,

is that if you just put the camera in the right place, then that is all you

have to do. The same thing with writing, I didn’t want the personal “I” to be

there.

At this moment, there were so many humans using social

media, exposing so much of their own lives. I decided when writing these essays

for the AJ, that I would never use any first person “me, my, I.” I could say

“we”, talk about ourselves collectively as humans.

KH

That’s an interesting place to start from.

DG

To write as dispassionately as I’d photographed. I set

this up as a rule. I’ve stuck to it.

I also told the editor at the AJ, “This has to be a piece of

writing that starts with a piece of writing about the picture shown.” There is

a simple repeated structure. I describe the content of the picture as precisely

as I can. This leads on to an exploration of an idea or theme. I will often

read four or five texts to develop the idea – I’m privileged to own an

extensive library. Then it’s about how you tell it in the clearest way. I spend

a lot of time rewriting sentences, so they stop feeling cluttered. Despite or

because of this editing, a clear voice appears. A lot of people have said to me

that they can hear that it’s not my conversational voice.

KH

It’s you. But the voice is distinct.

DG

I suppose one can feel it’s the same human telling the

story every week. There is then a correspondence, actually, between that taut

way of writing and what I’ve tried to do over a long period, and I still adhere

to, as a valid form of practice as a photographer.

…

Dead Sea (Near Wadi Mujib) I 2017

Credit David Grandorge

KH

I was interested that you talk about having a thesis by accretion. To finish, I wonder if we could just unpack that a little bit. What is that thesis now?

DG

I’ve seen a lot of things in the world, so inevitably

there’s going to be an accretion of ideas and thoughts. I’ve been to some quite

extraordinary parts of the world. I went to these places with enough intentions

for my photographic work, mostly about taming the exoticness of any situation

and trying to confer dignity on it. Especially when I was in Africa. I was very

conscious of the colonial problem, of being a white man taking photographs in

urban situations in Africa.

KH

Not being the white guy who’s come over to see and save the world.

DG

Yes. I wanted to do something a little different.

Subjects were chosen carefully. I only took a photo if I thought it was valid.

I was interested in looking at the similarities and differences between African

urban neighbourhoods and those in Europe and elsewhere. I did go off-piste, and

I found out that I somehow knew how to operate in these situations. I was calm.

I felt comfortable talking to the wonderful humans I met.

If I cast back to almost 10 years before that, when I left

college, I was rudderless. I didn’t know what I was going to do. I was asked to

teach straight away. I found I was a natural teacher.

Then, I was starting to take photographs. I was practicing

as well. I still could have gone that way. I just couldn’t afford to do it.

Also, as I said before, I felt uncomfortable with how architects and builders

related to each other. Then I was getting asked to do so many other things. I

couldn’t commit to a practice. It just wasn’t going to happen by then.

I realised I couldn’t just teach through charisma. I had to

have some strategy. The then head of school, Helen Mallinson advised me of

this. I am forever grateful to her. I think that my subsequent brief writing

allowed certain things to become clearer. Originally, I was interested in how

institutions worked, and then it moved onto to an interest in design strategies

that you could apply to any project. Then I moved on to pursuing very lucid

tectonic strategies to re-enforce this.

I am interested in helping my students to be critical

practitioners, to be familiar with both conventional and new ways of building,

to understand some, but not all, of the building regulations we have to address

in practice, to have a strong eye, to be very strategic, to be good at managing

information and to be able to manage disappointment.

With the photography, it was different. It was clear that

the sensibility I pursued emerged from the Düsseldorf School but I also had an

equal passion for the work of Wolfgang Tillmans, Michael Schmidt, Guido Guidi

and others. I also spent quite a long period around people in the fashion

industry and the arts world. I had lots of other influences coming at me.

Then you are getting to these positions where you have to

articulate when you talk about your work for different audiences. It takes a

while to learn how to do that. That, for me, was the thesis by accretion: that

I had the tools to answer questions about my discipline and how I practiced it

in different situations. That was enough for me. I don’t want to come out with

this fixed position, like the hedgehog. “It’s like this, and it’s like this

alone.”

You always have to be responsive. I had to find a form of

practice. This thesis through accretion is just about the accumulation of many

extraordinary experiences.

I’ve had the joy of being in Scotland and being taken to

remote places and documenting special buildings and the landscapes in between.

I’ve been to many parts of Britain and photographed buildings in some really

poor cities and towns. I’ve seen a poverty of opportunity there that I’ve never

seen in London.

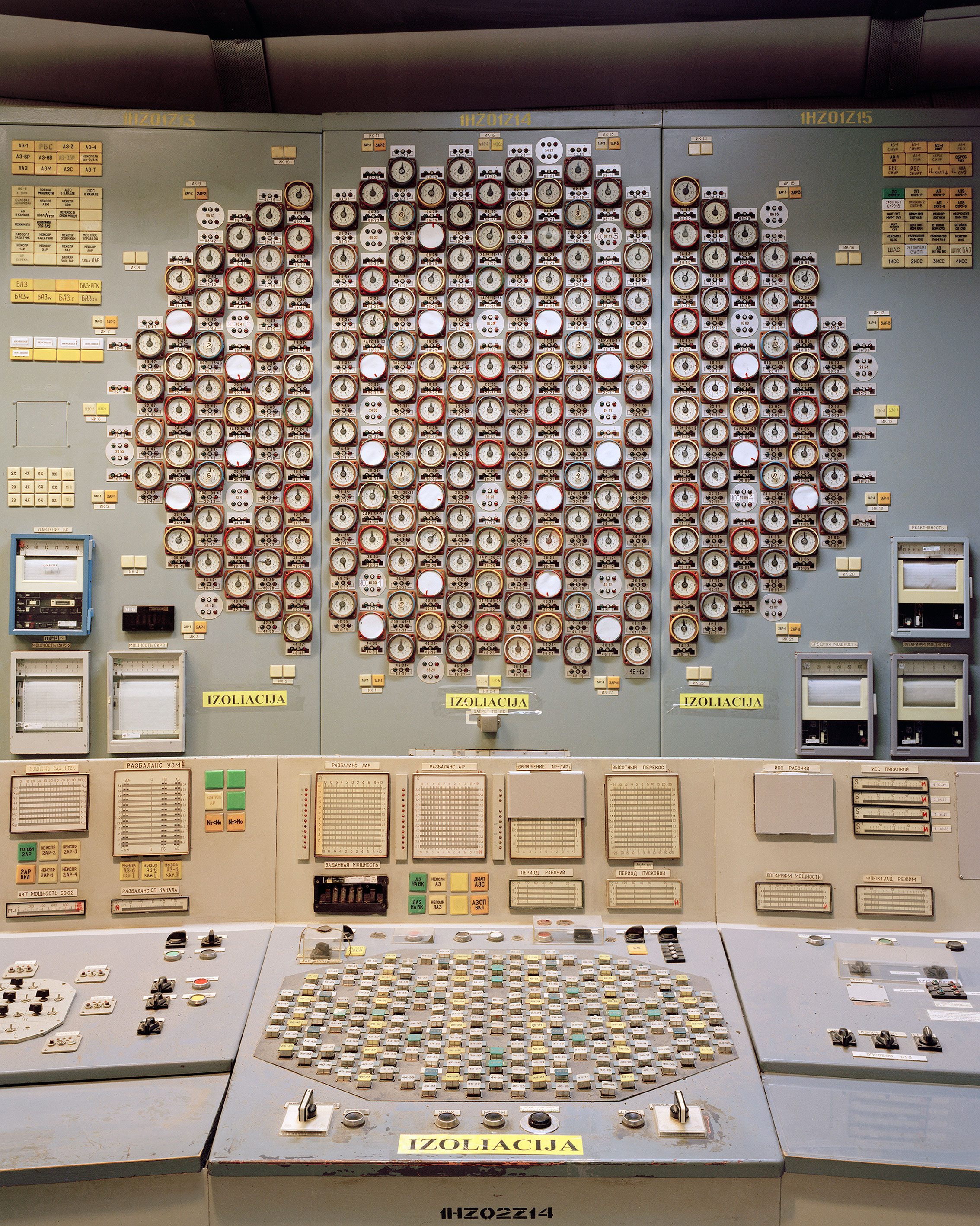

I’ve spent very immersive times in West Africa, East Africa

and North Africa. I’ve made research projects in the Baltic States, including a

road trip along the Estonian border with Russia. I’ve seen an incredible amount

of energy infrastructure. I’ve contemplated the Dead Sea. I’ve also met climate

change scientists in the Arctic after they were measuring the greatest extent

of glacier retreat ever recorded. That was seventeen years ago.

Ignalina I 2015

Credit David Grandorge

KH

Has the teaching been what’s given you the space to bring all these things together? For me, teaching has offered me something of a second education.

DG

One learns from

students and there is a little more space to think and ask questions about our

discipline, hopefully useful ones. For me, teaching, photography, writing,

designing, building and being a parent are all joined up. They all inform each

other.

KH

David. It’s been great to talk.