Credit Luca Bosco

BUSHRA MOHAMED

︎︎︎Callum Symmons

CS

How would you articulate a relationship with the past in your work: with the idea of inheritance and also disinheritance?

BM

It's really a pertinent theme within all of the work we do.

A big concern in the architectural profession right now is the acknowledgement of its status as a profession of power and dominance and its destructive capacity to perpetuate injustice in our world. The embodied and operational carbon of buildings that you can't escape, but also its links to colonial governance and legislative systems over land. We have a responsibility to first of all acknowledge that we're complicit in the current system. With that comes a huge responsibility to dismantle or disrupt those harmful inherited structures and systems.

I see my practice as an attempt to translate these very serious topics, from what can be very negative histories, into more positive and generative outcomes, even though I still believe as a practice, I'm complicit in the destructive tendencies of the profession, which is at times debilitating.

Through the work of the practice, I want to give agency and legitimacy to stories, or ways of looking at things that have historically been excluded. I've tried to practice in a way that carves a space for people like me, or people who look like me - women, people of colour – with a particular interest towards architecture from Africa, from South Asia, from the Middle East. I'm from Kenya, and I have a lived experience of African architecture, specifically Kenyan architecture. I'm not saying that we've never looked at the history of architecture in Africa and Kenya, or the Middle East, or India, but that we haven't looked at it from the perspective of it being a fruitful ground for progress, which is something I hope to change.

This is a process of redefining the terms of debate, shifting and dispersing the centre of architectural attention geographically and epistemologically, and making space for my lived reality. I've just reached a place where I’m able to do this in my own work.

CS

What inheritance do you hope to pass on through your practice?

BM

Specifically, I want my practice to pass on the inheritance of vernacular African architecture. I want to connect contemporary architecture to the vernacular of the African continent, to weave it into the canonical narrative, almost as a provocation to say ‘how might contemporary architecture develop if we value the vernacular or the indigenous, as much as we value the colonial or the modern?’

More broadly, I hope that the work of my practice will prompt other people to choose what they want to inherit and what they want to disinherit. It’s about getting to a place, culturally, where we have the agency to choose what we take, what we can leave behind, what we can choose to foreground or to background. I don’t think it is relevant to erase any parts of history: rather accepting the layered and interconnected nature of our world, and allowing choice in what you feel is valuable or what you find inspiration in, is where the richness lies.

Through my mixed identity, growing up both in Kenya andthe UK, I have inherited a plural identity. I hope to continue making space for plurality.

If I think about the profession in Kenya or in terms of Kenyan architecture, there's an acknowledgement that architecture, with a capital ‘A’, acted as a colonial profession: the capital city started as a settler colony, architecture was purely a system of dominance and control over land, the masterplan governed where Europeans would live, and just like the creation of the modern borders of Kenya, the legacy of this colonial control still exists. From this perspective, architecture can be understood as a colonial construct. Therefore it makes sense that many would advocate a rejection of the main levers of the architectural profession, such as architectural drawing styles, the elements of conventional practice, of ordering and controlling space and how people move through space, instead seeking to find new tools that don’t stem from that colonial heritage. However, in understanding the skill and knowledge of the vernacular architecture of the region and the tools those communities used there is a very interesting new type of architect that can emerge: one that builds on and uses aspects of both.

I've chosen very consciously to engage with those existing practices and methodologies to challenge and further understand how they can be dismantled as tools of power. That is to say, okay, while we might still use these ways of drawing or ways of thinking about architecture which originates - especially in the context of Kenya - as colonial practices, we do so by reclaiming agency over them, using them as tools to deconstruct power.

It is important for me to pass on those ways of practising architecture: valuing the inherent intelligence of low-tech and vernacular building techniques, methods that consider a circular economy, including existing knowledge systems, and how space can foster communities. It’s about giving the possibility to incorporate disparate parts of one’s identity, aspects of one’s self that might not immediately be understood as architectural in a conventional sense. This process is related to how we define what architecture is. Can we take influence or inspiration from other aspects of our material or visual culture? Can we incorporate our physical culture, our rituals, into our architecture?

That is the power of practising in the way that I do, using the conventional, historically established tools of the architect, but using them to practise in a way that is welcoming, that is about unearthing stories, in a way that looks at wider aspects of our visual culture, in addition to those typically contained within architectural practice.

In this sense, I think it's deeply political and important to be conscious of our visual world, our physical world, and how we design and make it. I think it's a very personal, human, concern, especially in terms of representation, to be conscious that the physical and visual world we share has had many different people contribute to it.

Through teaching especially, you can lay a foundation for this kind of a change. At the teaching unit I led at Kingston University about the compound house, for instance, we’ve been able to shift focus onto a different way of thinking architecturally, locating the centre of our attention in a different place in the world and then considering it from a perspective that doesn't centre western architectural models and types.

CS

While there is a radical, political, cultural project embedded within the work of Msoma, there is also a certain adherence to inherited systems or structures. There's a certain desire for continuity, a capacity for reconsidering elements of the past in a new way, rather than trying to wipe the slate clean.

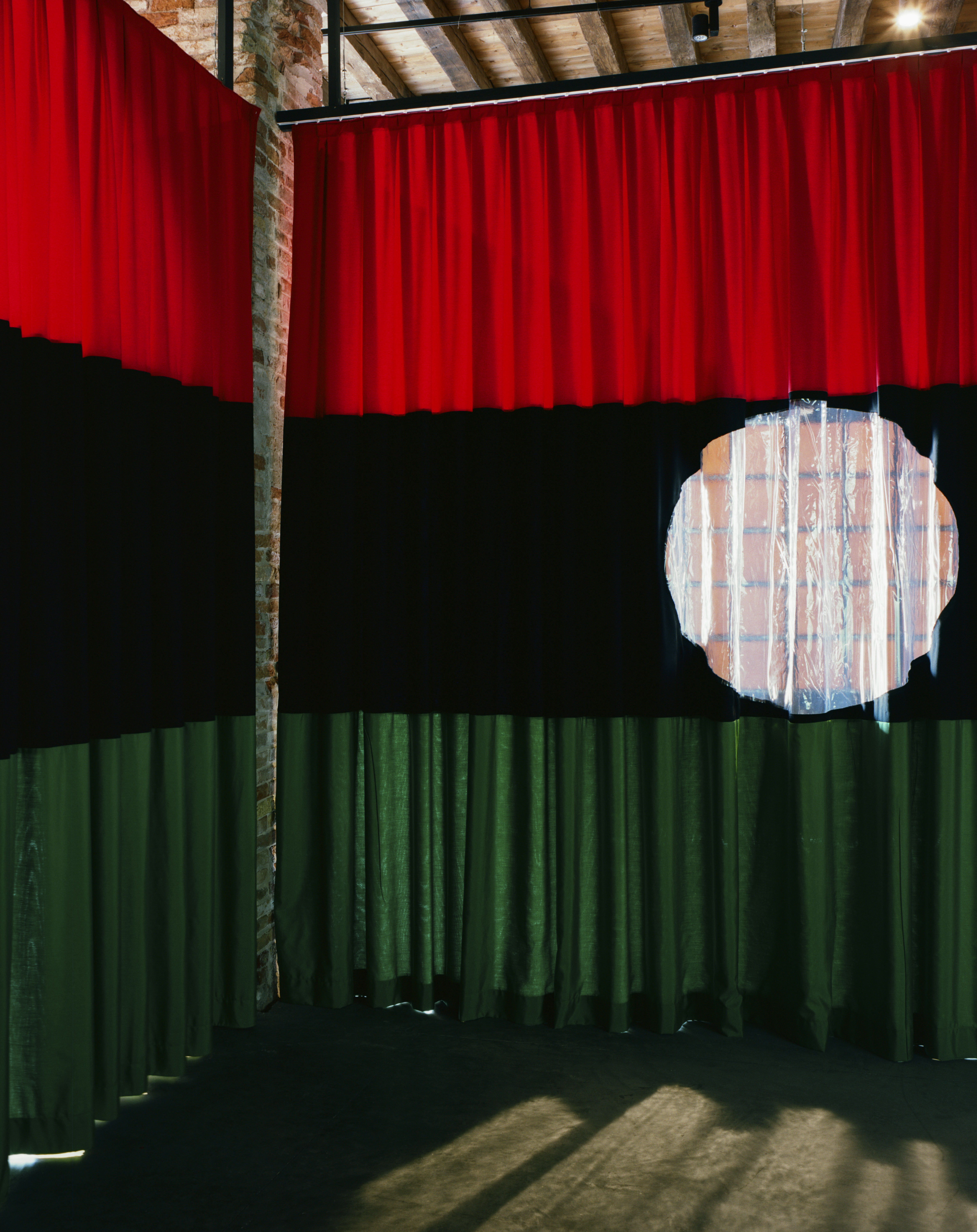

Tropical Modernism: Architecture & Power in West Africa

Exhibition at the V&A Pavilion of Applied Arts, responding to the “Laboratory of the Future” theme for the 18th International Architecture Biennale in Venice 2023. Co-curated by Bushra Mohamed, Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Dr Christopher Turner.

![]()

Credit Luca Bosco

![]()

Credit Luca Bosco

![]()

Credit Luca Bosco

Exhibition at the V&A Pavilion of Applied Arts, responding to the “Laboratory of the Future” theme for the 18th International Architecture Biennale in Venice 2023. Co-curated by Bushra Mohamed, Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Dr Christopher Turner.

Credit Luca Bosco

Credit Luca Bosco

BM

If you think about it through the metaphor of language - drawings, plans, sections, elevations, axonometrics, models, etc. are the architect’s language. Rather than try to teach new ideas in a new language, I am trying to use the architect’s language that I have been taught and that everyone already speaks to convey new ideas.

Msoma, the name of my practice, is a Swahili word, meaning ‘reader’. In a sense, it’s something different, which maybe most people would not immediately understand, but then everything behind it is in English, which you do understand. It’s one way to acknowledge the practice’s unconventional, progressive approach, which foregrounds a less dominant language through the conventional language that everybody speaks.

CS

I think that's clear. There's an aspiration for collectivity, or a positivity in that approach, that is inspiring. It's an additive rather than a subtractive attitude.

BM

I think that often in discussions of colonial histories - or the histories of parts of the world which have been affected in a negative way - we can dwell on the negative, in a way that tends to be really paralyzing. It almost frightens people to a degree, into a belief that they can't do anything to make a change. I think that that's an unhelpful state to be in, to be so petrified by the weight of history that you can't move forward.

I always think it's much more useful to think about what this means for what we can do, rather than getting frozen in that state of negativity. It's that message of agency that I want to pass on through my practice, with a trajectory of hybridity within architecture. Pushing the idea that nothing is homogenous, and fixed: it's actually quite dynamic, interconnected and heterogeneous.

That's what I want to foreground with my work, an understanding that the physical world that we live in is layered and hybrid and that there are connections that tie us together globally, nationally, regionally, that we can and should make explicit.

Through research, I want to foreground West African and East African architectures, specifically the compound house. To show that it is a valuable cultural and architectural resource for the whole world to tap into, and not think of it as a primitive resource. This ties to my positive perspective, a form of practice that focuses on affecting change.

I think that's clear. There's an aspiration for collectivity, or a positivity in that approach, that is inspiring. It's an additive rather than a subtractive attitude.

CS

How do these discussions manifest themselves physically or spatially, or is this even possible? There's always the possibility that architecture is simply incapable of containing these conversations.

BM

I think this question is related to the question of what architecture is, and what is architectural practice. For me, it's really important to, yes, build and make spaces, but also to curate, to research, to write, and to teach.

A recent project completed by the practice is the Tropical Modernism exhibition, which was first shown in the Arsenale at the Venice Biennale 2023. This project captures the way that we are often working across multiple disciplines, and roles, in a hybrid manner.

Fundamentally, this was a project about unpicking and rewriting the story of Tropical Modernism, the prevailing version being about European architects who went to West Africa as part of the 20th Century colonial project and made buildings which applied a Eurocentric model of modern architecture to this new “primitive” place, and how they adapted it, first to the climate and then to the culture.

What past research doesn’t tell you, is why they wanted to build in this part of the world: the extraction of people, gold, aluminium, cacoa, energy that follow this seemingly generous act of development.The exhibition asks questions about authorship, and how travelling around the region fostered a cross-cultural exchange. It asks questions about who is given opportunity and how European architects in that period used the colonies to test ideas and make a name for themselves.

The exhibition unpicks this narrative, looks at it in more detail, it fills the gaps in the archives, understands and highlights the actors and figures who were part of that movement and

had not previously been included in the story. It simultaneously reconsiders the simplistic narrative that Tropical Modernism is only a negative, colonial project. The work was about looking closely at this moment of architectural history and then rewriting its story accurately and inclusively.

The reality is that, of course, there were a lot of local people, a lot of Ghanaian architects involved, and of course, the main protagonist of the story being Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, who

found a way to co-opt the modern movement for his own political ambitions.

The narrative of the exhibition was about acknowledging their part in the movement, reinstating their agency of this being an architecture that was co-produced, that is now a fundamental part of both Ghanaian and British history

.

It’s an investigative process which doesn’t take everything at face value and really understands how uncovering a story and revealing a narrative can actually give agency to people. That's not necessarily a conventionally architectural tool, but it is a tool that we, as architects, often use: the narrative and storytelling of our work, right?

And then secondly, through curation, it is about how you can tell a story in a very clear way so that anybody can understand it, and it doesn't take an architect who has studied for seven years to really grapple with the concepts. I've found throughout my career and my education that it's really stifling when, as architects, we over-intellectualise ideas so that the general public don’t understand them.

And then finally the Tropical Modernism project was about exhibition design. Which, in some ways, is the simplest of the various roles. How do you lay out the research and the narrative, so that the journey that people go through is straightforward, they take in the content in a way that's comfortable, and then they get to a place where they feel like they've learned something or experienced something? In a way, it’s a process of setting a stage, or even a background. In this case, we remade the facade from Fry & Drew’s first project in Nigeria

at the Univeristy of Ibandan

and used it to hold the content of the exhibition.

I think the Tropical Modernism exhibition presents a very good example of the different roles that we often adopt, that the practice is able to adopt. In a way, it’s a process of world-building.

How do these discussions manifest themselves physically or spatially, or is this even possible? There's always the possibility that architecture is simply incapable of containing these conversations.

Islands

Exhibition for the Design Researchers at the Design Museum, London. Msoma Architects, 2023.

![]()

Credit Felix Speller

![]()

Credit Felix Speller

![]()

Credit Felix Speller

Exhibition for the Design Researchers at the Design Museum, London. Msoma Architects, 2023.

Credit Felix Speller

Credit Felix Speller

CS

How do you begin to combine this model of cultural production with a more everyday architectural practice? I’m conscious that Msoma has worked on a number of projects aside from exhibition design.

BM

As we are relatively young, each project we work on is important and helps us develop the values of the practice through its narrative. We try to tie the work to the position of the practice, and to the material and theoretical spaces and cultures we are trying to work within. Whether it's a conversation that's had with the client or not, it's something we definitely talk about between ourselves.

For example, we worked on the concept design for a workspace called Patch, in Twickenham. From the client’s perspective, they chose us because we are a diverse practice, and the communities they are trying to engage are diverse, and they wanted to somehow create something that speaks to these diverse communities. But, that is a very generic goal, it's very difficult to build an appealing narrative around the desire to create something to appeal to everybody.

The question is about finding a narrative where you can introduce an idea for the project. Here, the idea was to introduce a music production space on the ground floor and then to have spaces for knowledge exchange above. We built a narrative around communities that historically were in Twickenham, that were in South London, who had had very clear connections with music knowledge, production and exchange.

Another project, related to the notion of global identities that I discussed before, is a collaboration with Adam Nathaniel-Furmanin for

Somerset House, an 18th Century Georgian quadrangle on the River Thames. The goal was to shift the architecture of the spaces towards the global identities of the people who use the spaces every day, and we built a narrative around colour, pattern, and texture, which wove these new narratives and voices into the space.

We looked at the locations that were part of the British Empire when the main portion of Somerset House was built, in the 17th Century. At that time the British Empire wasn't as large as it got in the 18th and 19th centuries. So, we pulled out colours that were meaningful, and textures and patterns to those contexts, and brought them into the Georgian space. This was important to us because although, through the British empire, the building would have been connected to all these different places, there was nothing in the physical architecture of the space that told us about these connections. This process becomes more important today if we want to acknowledge these kinds of histories and narratives.

I would say this in itself was actually very radical for the client. The attitude towards historical spaces in the UK tends to be very conservative, very much rooted in the preservation of and the continuity of the history of the existing building,

rather than introducing or making visible intangible historic connections.

How do you begin to combine this model of cultural production with a more everyday architectural practice? I’m conscious that Msoma has worked on a number of projects aside from exhibition design.

CS

It's operating semantically, operating through references and signification, but drawing on a different set of references than people like Charles Moore, Robert Venturi or Denise Scott Brown would have done in the 1980s, with a different set of goals.

It’s clear how this project manifests itself through image and surface, it seems interesting to ask about the formal, spatial translation of these conversations?

BM

The distinction between the postmodern work of the 70s/80s and what we are doing now is that the post-modernists explained their ideas through intuition and whimsy. What we are doing is more rational, with a wider ambition towards equity and equality.

In terms of Msoma’s work on housing - the new-build houses or the apartment building in Kenya - those very much reference the spatial logic of the compound house, an incredibly important reference to the work of the practice. Our adoption of this reference really speaks to the notion of historical continuity: how history can inform our contemporary and future culture. It’s also about simply giving validity to the indigenous vernacular architecture of Kenya

that has been ignored or deevalued for a long time

.

We also try to materially reference the local materials that would have been historically used, for example the use of wattle and daub or thatch. There's a nod to history here, but we also find it really important to evolve this aspect of the vernacular.

Instead of the roof being made out of the reed thatch or palm thatch that would historically have been used, it is made using recycled plastic fibres, for example. It's not necessarily a matter of building exactly as you might have done before, but instead thinking about how we can use contemporary materials that might be cheaper or more readily available now, yet still reference the history and vernacular of a place.

In exhibition design, what is often important is to spatially convey a tangible connection to other places, as well as an intangible connection to concepts and ideas. We've tended to use light, for example, to convey the intangible. The layout of the plan also can be a way where we communicate the intangible, experienced spatially.

I've also found that drawing from other aspects of our material culture, or our visual culture can be useful. There are these funerary statues, for example, that are used by the

the Mijikenda

in Kenya, a carved totem of the person who passed away. And they're really beautifully detailed and crafted. I think they're incredibly architectural when you begin to look at them formally. Looking at cultural artefacts and objects such as those for reference and trying to translate that into architecture is another approach we often explore.

For the most part, though, and especially in the exhibition design, our work tends to be based upon colour, pattern, or texture. Mostly because - and I do think this is a big thing - it's cost-effective, and it's cheap. So that tends to be the way we do it. I also think there’s something interesting to be explored in the use of fabrics, about a domestic quality, or a femininity, maybe, or softness.

I think generally, fabric has been a really easy way to transform a space from a very generic to a very celebratory condition. In our exhibition ‘Islands’ at the Design Museum, we wrapped a curtain around the whole space and created this very dramatic curve at the end: using fabric allowed us to achieve this spatiality very quickly.

We did a similar thing in our exhibition of the work of Althea McNish, who is a British Trinidadian textile artist who obviously worked a lot with fabric. Using fabric in the presentation of her work allowed us to convey the softness and femininity that she brought to her art.

This example in particular is tied to the first question of inheritance. For that reference for the Althea McNish exhibition, the reference of the curved curtains, we looked firstly at that Lily Reich and Mies reference of the curtains in the exhibition: it's a deeply established image of how curtains can be used to adapt a space very simply. I wouldn't disregard that reference simply because it is a Western European reference. But then we also looked at the Caribbean, the West African, the West Indian front room, and Caribbean front rooms and how curtains are used there in a dramatic way to frame the window.

I’d go back to my point about giving agency to be able to choose different references. It’s about making sure that the references are not just the established ones of Mies van der Rohe constantly, but you also have agency and legitimacy to pull from your own lived experience, of how fabric is used from your own culture, to complement the established, canonical reference of Lily Reich and Mies.

It's operating semantically, operating through references and signification, but drawing on a different set of references than people like Charles Moore, Robert Venturi or Denise Scott Brown would have done in the 1980s, with a different set of goals.

It’s clear how this project manifests itself through image and surface, it seems interesting to ask about the formal, spatial translation of these conversations?

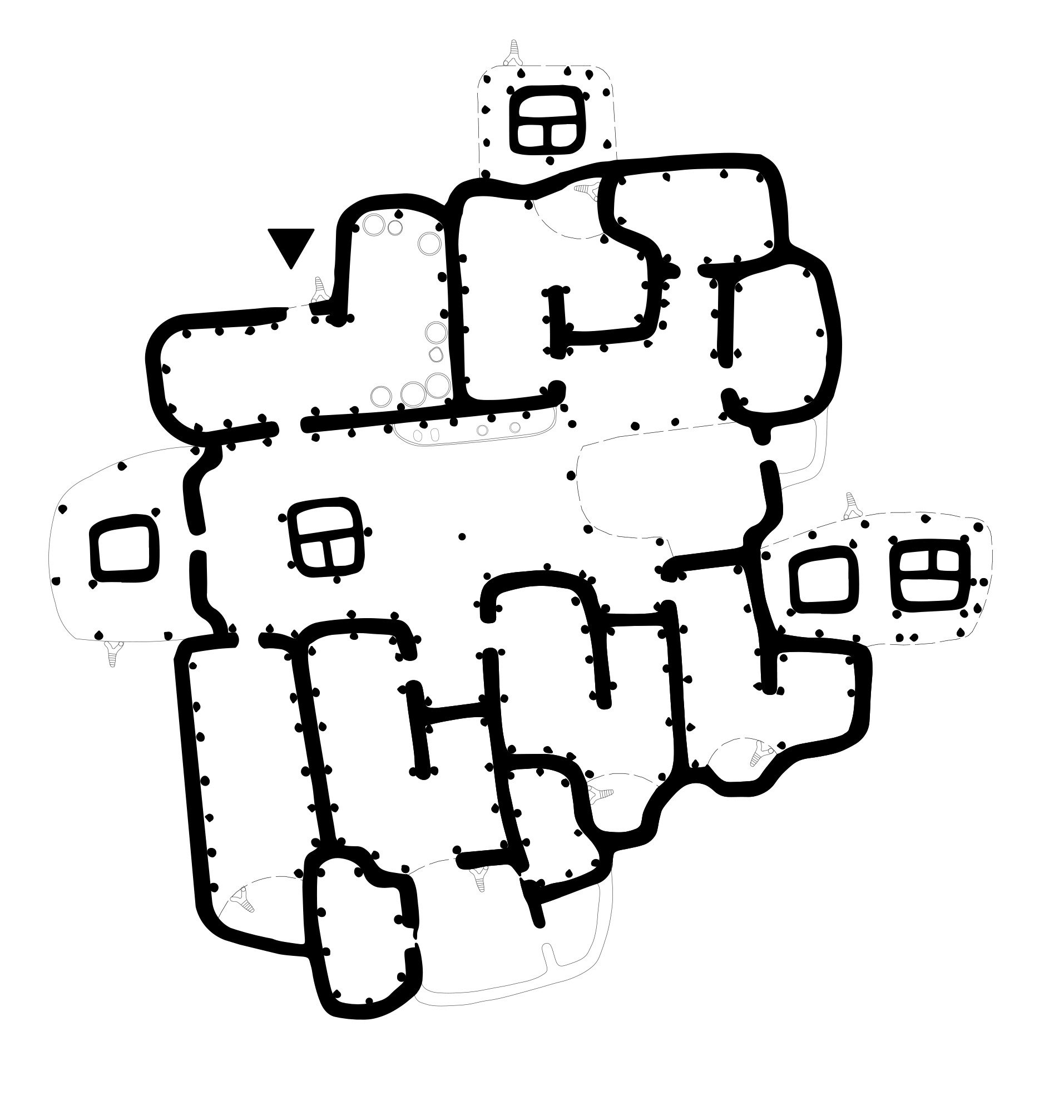

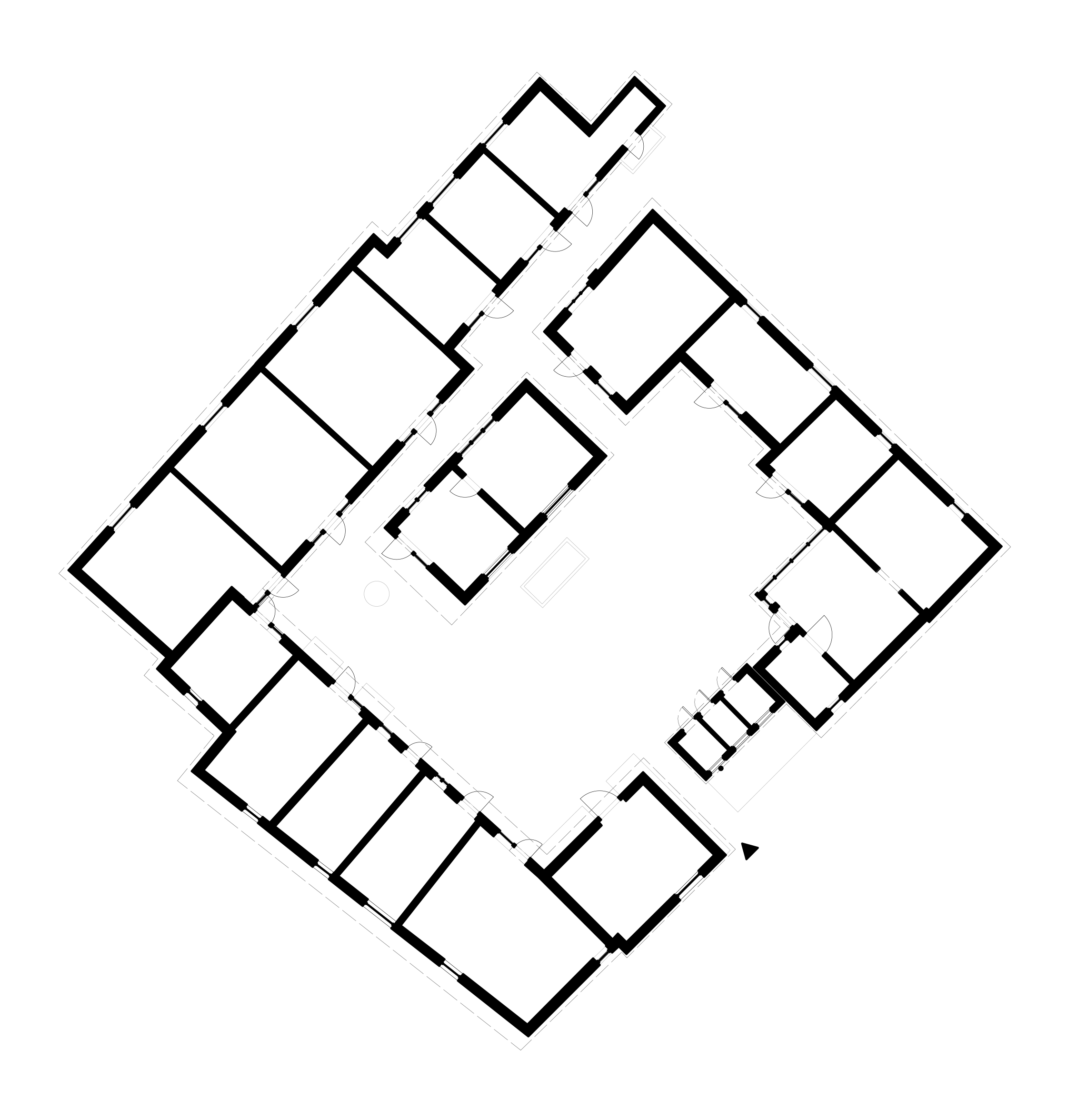

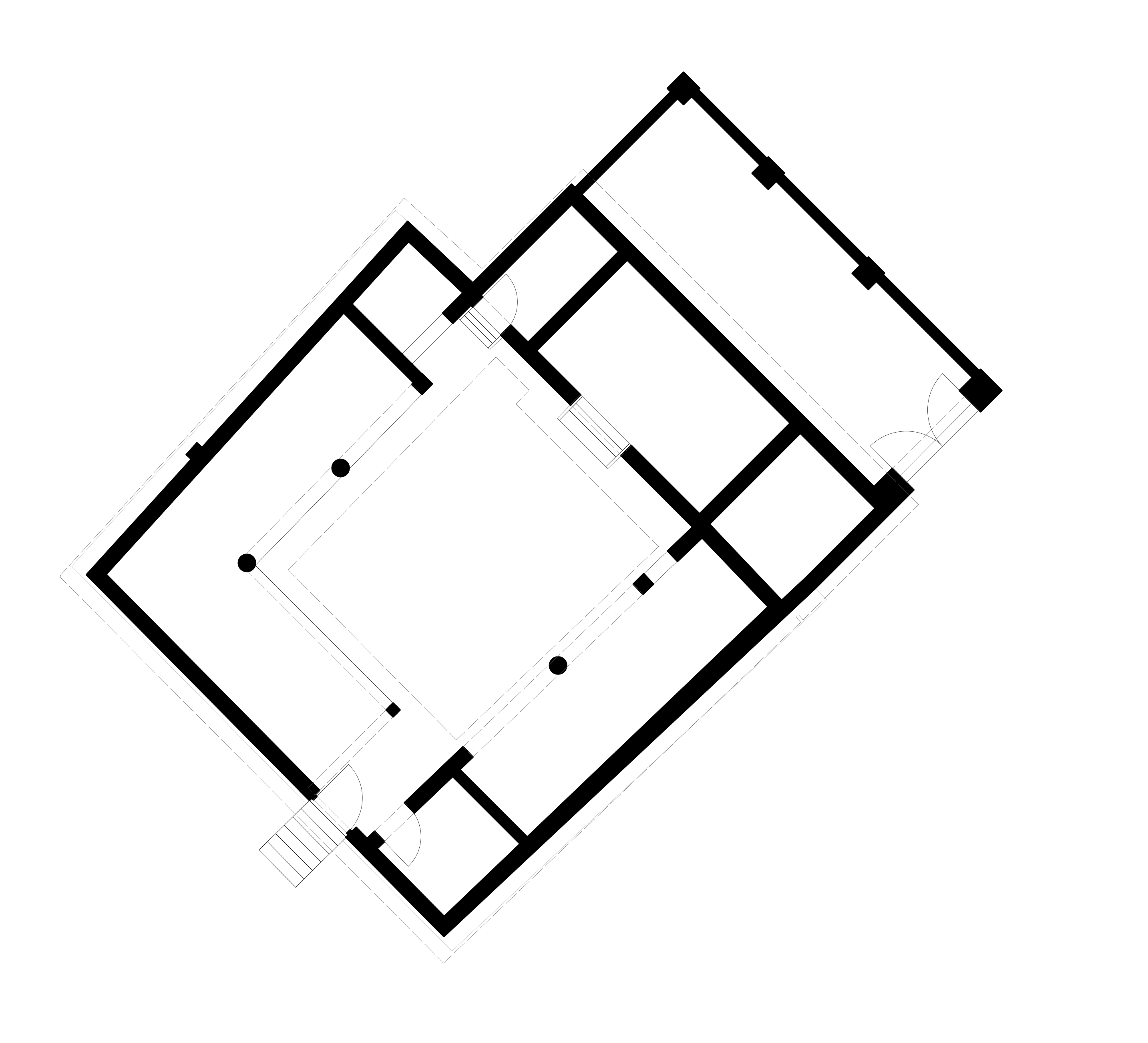

Compound House

Ongoing reasearch documenting the African compound house as typology, investigating its historical and contemporary condition. Bushra Mohamed in collaboration with Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Mark El-khatib.

![]()

![]()

![]()

All drawings credit Msoma.

Ongoing reasearch documenting the African compound house as typology, investigating its historical and contemporary condition. Bushra Mohamed in collaboration with Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Mark El-khatib.

All drawings credit Msoma.

CS

You touched upon it there, but could you expand more directly upon your research into the compound house typology? I understand it’s a body of work intrinsic to your practice, that has been conducted over several years. It seems a salient example of the spatiality you are discussing.

BM

I grew up in a compound house in Kenya, which formed my understanding of the term ‘dwelling’. Furthermore, I was very conscious that African architecture sat very low on the hierarchy of knowledge in the West, and at the time vernacular architecture was also underappreciated as architectural knowledge. I wanted to explore this typology academically, as I felt that it represented a missed opportunity for housing on the continent.

Therefore, destigmatising and reconsidering this historic domestic typology has been a primary focus of my research. At the same time, it’s about how to encourage a more environmentally conscious way of building that also references a cultural inheritance, places value upon that history, and doesn't just ignore it and start from colonialism or modernism.

The compound house project first started as a teaching unit brief at Kingston, and it has since evolved into a book, an apartment housing project, and a house for three families. Along the way, it also evolved into various texts for different publications: the AA files, Sound Advice. In effect, it’s been a process of world-building, as I mentioned before. I had to write those things and put them forward to get other people to understand why it's important to look at this architecture, in addition to other domestic courtyard typologies from throughout architectural history.

The typology of the compound house itself is defined by a collective space in the centre of the dwelling, which acts primarily as a gathering space and a thoroughfare, but becomes the spatial nucleus for the home. You have to go through the central space, the compound space, to get to other spaces. It becomes like a capsule, a sort of polyvalent space in the middle that can have lots of different functions. It operates similarly to a corridor space in other typologies, but here it is typically an outdoor space. Even when it's not external, it's still a more generous space than a typical circulation space might have. It has higher ceilings, it is much more celebratory, it's a spatiality not dissimilar to the corridors of stately homes which might hold artwork that the resident family was collecting. The compound room becomes this space to celebrate elements that are really important to the community of the people living there.

I think in general, the research into the compound house typology has helped me detach, as a designer, from conventional UK housing standards and really reframe the value of domestic space. One of the questions thrown up by the research is about translating the spatiality of the compound house for UK domestic standards: for instance, if we take the terrace house, is it possible to have a living room in the centre of the plan? Which might help open up to other spaces in the house. In general, it caters well to contemporary domestic developments, particularly in providing high-density dwellings. It's an opportunity that you can sort of translate the compound typology into. Its emphasis on multigenerational living can be translated to support childcare or elderly care within domestic typologies.

There is also an important process of destigmatising some of the connotations with these buildings: historically they have been referred to as mud huts, symbolic of a primitive or barbaric culture. However, as we grapple with the climate crisis we come to understand the value in these architectures that are inherently circular: they are made of natural and biodegradable materials and considerate of the multispecies that we share this planet with. For example, with the Islands exhibition at the Design Museum, which was curatorially exploring how islands as earth formations have come to affect our physical environment, we chose to use earth construction to revalue earth building.

I think it’s important to challenge the suggestion that this is somehow a lesser form of construction, and value the compound houses for their visual characteristics, their beauty, but also the embodied architectural and constructional knowledge involved in the crafting of their timber frame, or the conical thatch roof, or the carvings in the earth floor and walls. The question is to then think about how we might translate that cultural and architectural knowledge into contemporary standards and contemporary means, without compromising it.

This process of destigmatising is required in Kenya too: because of globalisation, there is still a much higher value on Western aesthetic standards and modern materials such as glass, steel, and concrete. We now know that these materials are very damaging to our planet therefore we need to consider how we use them. This becomes especially significant in Kenya, where there's a huge need for housing, and a huge amount of construction is required. If you construct this new housing using western, conventional typologies, en masse, it is going to have a huge environmental impact.

You touched upon it there, but could you expand more directly upon your research into the compound house typology? I understand it’s a body of work intrinsic to your practice, that has been conducted over several years. It seems a salient example of the spatiality you are discussing.