CONTACT

Custom Lane,

1 Customs Wharf,

Edinburgh,

EH6 6AL, United Kingdom

mail@aefoundation.co.uk

DIRECTORS

Nicky Thomson

FOUNDING DIRECTORS

The AE Foundation was established in 2011 to provide an informed forum for an international community of practitioners, educators, students and graduates to discuss current themes in architecture and architectural education.

![]()

ROLF JENNI

TOM WEISS

JAN KINSBERGEN

︎︎︎Samuel Penn

ARCHITECTURE

SP

We invited Rolf and Tom to come and present some of their ideas here today. We also asked them to suggest someone that they see as a critical friend or collaborator. And so they asked Jan to join us. We are very happy to have him here. He will also talk about his work and then we will open it up for discussion.

RJ

Thank you Samuel. Tom and I run an architecture office in Zürich called Raumbureau and today want to discuss our discipline, to reflect on architecture in general and questions that preoccupy us in our own work. We will present a series of topics and explain them through our projects. We have invited Jan Kinsbergen to give a talk about his own work. We rent office space in the same building and are good friends.

The first topic we would like to talk about concerns having ‘an unprejudiced view’. Our work and research as academics is a fundamental part of our practice. It is concerned with the observation and interpretation of the processes of urban transformation. At the universities where we work we are part of teams that are comprised only of architects. In this context, through teaching and research, we are able to sharpen our visual and spatial senses, which are as important to the architect as the ability to connect reality to their imagination. When we begin a project we look at it from a naïve point of view. We look at things ‘how they are’ in an attempt to understand the specific phenomena in a given context, whether familiar or unfamiliar. The photographic image is a crucial device in understanding these everyday realities. These observations form the basis for us to discover potentially hidden phenomena and to begin to deduce the processes of urban transformation. Our research isn’t just a mechanical or pragmatic representation of data; we also look at it from a subjective point of view. The reality we describe is objective, analytical, but paired with the interpretive and creative qualities of our imagination as architects. In his lecture ‘Science and Reflection’ Martin Heidegger defines the word ‘theory’, which originates from the Greek verb ‘theorein’ as: “To look at something attentively, to look it over, to view it closely.” We believe that by training and sharpening these abilities we are more capable of capturing the current conditions of urban society. In our research we use the instruments of drawing and mapping to make a precise and unprejudiced interpretation of phenomena.

The second topic is ‘typological thinking’. A substantial part of our work is about dealing with larger areas in the city which are very often brownfield sites; areas between thirty and fifty thousand square metres, a scale that far exceeds the single object. Because of this shift in scale we have to question the relation between architecture and the city. In our experience, and with commission like this, the clients often start with a preconceived image of their future development, for instance a green quarter, eco-quarter, a technology campus and so on. For us as architects these preconceived images are not helpful and can even blur the appropriate agenda. We would much rather talk about things like access or circulation, or how the building mass is organised. It’s at this moment in the process that type, or the application of typological thinking become relevant to us. To avoid confusion it might be useful to clarify that we don’t think of type as something which forms the basis for duplication, like for example in the Werkbund debate on ‘type’ during the first half of the twentieth century, but rather we think of it more like the typology used by Aldo Rossi. Type or typology in his context refers principally to the idea, or the reduced essence of something from which a model, for example a building can be developed in different ways. Yet the goal of typological thinking, the reduction to archetypes, is not primarily to create a catalogue of applicable types, but rather to discover and to recognise the characteristics and possibilities of the task and the context. Typological thinking relates to the whole, to the interrelations of things, to the extraordinary as well as the ordinary. It allows us to clearly define questions beyond arbitrary problems of form or style and to begin to establish a hypothesis from which a design proposal can start.

Here we present two projects to illustrate the influence of typological thinking. The Escher-Wyss area is a large industrial site in the western part of Zürich comprising of approximately seventeen hectares of land. Due to the continuous expansion of the city westward along the main infrastructure arteries the site is now one of the most prominent redevelopment areas in Zürich. The plan is to keep the existing Hi-Tech industries in place and to add housing and services. The site is an interesting example of a continuous transformation of this part of the city over a number of decades. In the area specific building types have fostered a transformation processes, which after being abandoned have attracted particular user groups. Of special interest are the large hall-types of former factories. Our proposal included the strengthening and the growth of typological clusters, which would help cultivate the existing diversity of programs and users in these different areas.

![]()

fig. 1

Escher-Wyss Areal

Zürich 2006

Starting with this hypotheses our work was mainly the subtle supplementation of the existing types to create what we described as group-forms, specific but flexible structures, in which each group of buildings has its own identity and possible use. What you see in the slide are examples of these clusters and amalgams of buildings. The development strategy is not bound to any particular style. The façade and the appearance of the building remain undefined and open.

TW

This is a housing project near Lake Geneva on a site with a very diverse existing fabric, single-family houses, family gardens, industrial structures, a train station, and a public park. The client, the municipality, recognised the quality of the diversity and was willing to explore different forms of development. We proposed two apartment buildings that complement rather than replace the existing urban tissue. What interested us here was to intervene in a way that would allow us to keep as many of the existing features of the site while at the same time generating specific spaces around the new buildings. We were investigating the possibility of complementary building types, which like this slender cross-shaped building, would restructure the exterior area and frame a variety of urban pockets and collective spaces.

![]()

fig. 2

Competition visual

Nyon-Les Plantaz 2009

The next topic is ‘a vocabulary of the public’. In considering this we would like to quote the architecture theorist Claus Dreyer, who in his essay ‘The Crisis of Representation in Contemporary Architecture’ wrote: “There is no common language in architecture through which common experience, ideas, hopes, values, traditions and conventions could be expressed, just as there is no common ground in society for these issues. There are only a few outstanding individuals with a great artistic potential and almost god-like reputation who have the opportunity to articulate their private language by unique means, and to present it to the public.” We are less pessimistic than Dreyer and try to look beyond the contemporary fascination with spectacle. Questions of the common or the public in architecture are still important to us. Yet it is true that today the idea of representing something common is more often than not seen as anachronistic.

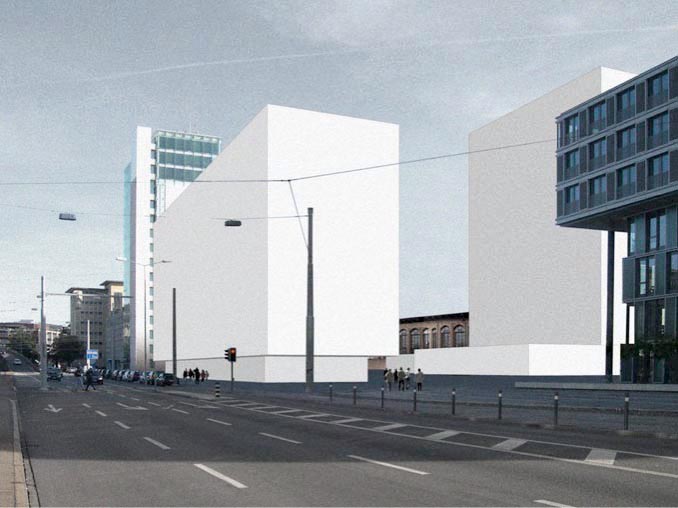

This project was to design a building in a small town to include their municipal council assembly hall as well as space for the five departments of the city. In the brief, the issue of representing the city’s government was merely treated as a matter of efficacy. The dimension of the building and its outline was already determined, the depth corresponded to that of a current office-building type. These relatively unfavourable conditions were the framework from which we began to explore a public vocabulary. A point of interest in this project is the use of archetypical form or strong form. Instead of camouflaging the banal symmetric and repetitive building shape we tried to dwell on its calm and elegant appearance. What fascinated us in the design process was the use of a loadbearing structure. We proposed prefabricated exposed concrete beams spanning eighteen metres and visible from the inside of the building. Mass and tectonics were used as a way to create a powerful but calm architecture, which would provide a strong frame as a contrast to the randomness of everyday life inside the building. The aim was an architecture that with its simple and archaic appearance could reveal a deeper sensual multiplicity of meaning, and a possible path to common architecture. Further potential to articulate a public architecture lies in the treatment of the ground floor.

![]()

fig. 3

City-hall elevation

Biel Bienne 2009

Here we proposed massive columns to carry the upper floors. The facade of the ground floor is set back and transparent on all four sides, enclosing a generous foyer space. A plinth, a pedestal the height of a couple of steps on which the building is positioned, reinforces this classic articulation of a ground floor. The plinth is an element that was virtuously applied by Mies van der Rohe in many of his buildings. The elevated plinth anchors the building in the undetermined area of the square, and yet, similar to a podium, it increases the political meaning of the building as a place where controversies confronted and negotiated. The plinth becomes a stage that is able to expose the public as well as the political life of the city, but also allows people a distant view back to the city, a relationship between the city, the public space and the subject, which Roland Barthes describes as: “An object that sees, a look that is seen.” In original French: “Un objet qui voit, un regard qui est vu.”

The next public building is a sports centre for a small municipality a thousand metres above sea level. It’s a competition we won together with Jan. The design includes a clubhouse, playing fields for the local football club, and public recreational facilities. In a landscape occupied by agriculture and forestry the building serves as a public access point to the landscape for hikers, cross-country skiers and the like. Here again the public agenda was a starting point for the design. The building is flat and square-shaped, 28 by 28 metres. It includes a café with kitchen, team dressing rooms, multipurpose room, and technical rooms, each oriented to one of the four sides of the building to allow separate access to all spaces and independent operation of all the program parts throughout the year. Again it’s a very archetypical form, a square, a plinth as base, an open and flexible space, and a massive roof carried by some columns and walls, a simple building. But what interests us is not the simplicity devoted to the aesthetics of economy, whose aim is to establish an interdependence of form and structure; here simplicity is rather a means to approach the question of strong form and its expression.

![]()

fig. 4

Sport-complex Lienisberg visual

Walchwil 2011

The focus on mass and tectonics is sometimes overemphasized, and sometimes questioned. The principle consisted in structuring the building to be as viewer-friendly as possible, both expressively powerful and readily understandable. The appearance and its effects were to be enjoyable without any prior knowledge. That’s why an approach towards a common architectural language through simplicity and a strong form here becomes effective on the level of perception. Here we would like to quote a colleague, architecture critic Martin Tschanz: “These buildings that appear so simple, even bleak at first [...] a deeper, sensual multiplicity of meaning, often a greater multiplicity than postmodern architecture was able to achieve. The result, not infrequently, is effects of impressive beauty that can be enjoyed without any previous knowledge.” The simple building and the strong form become a formula for processes that incorporate as much as they can, another prerequisite for a common architecture.

RJ

The last topic we want to present is ‘climatologic architecture’. This is another important aspect of our work, our critical relationship with ecologic sustainability and the current trend of producing highly technologically equipped buildings that are not the result of the natural and prudential relationship of man and his environment. Today increasingly standardised and normative policies lead the discourse of ecology in architecture. To work in a completely different climatic context, the hot tropical climate of Hong Kong, offered us the chance rethink our approach in a radical way. It’s a reflection on the current developments in building economy and technology. The ‘50s through to the ‘70s were characterised by a highly intelligent approach to architecture with regards to its relationship with extreme climatic conditions. This approach included very simple measures such as smart positioning on the topography in order to allow wind circulation, or the use of brise-soleil for sun-shading, or the use of the massive concrete construction for the regulation of the temperatures during day and night. Today, these very simple and ‘low-tech’ achievements with their impressive spatial qualities have almost entirely disappeared in Hong Kong. Instead there is a proliferation of a generic, globalized architecture. Despite the sun in this condition, most buildings have structurally glazed facades without solar shading and air-conditioning that generates huge energy consumption. It is reference to the legacy of the modernist era and especially its very simple logic and legible handling of the given climatic and environmental condition. This is our starting point for the Campus of the Chinese University proposal. The building shown on this slide is a beautiful example of just this sort of approach. It has no climatic separation between inside and outside, no windows and no membrane. It’s just a few steps from our proposed project site.

![]()

fig. 5

Campus building

Hong Kong

The new teaching building for the Architecture Faculty is consciously conceived as a continuation of late modernist public buildings located on the campus. With the new building we wanted to extend the sequence of stadium, canteen and library, by reinforcing the continuation of the existing setting. Thus the robust horizontality of the new building plays to the existing architectural composition and language of the campus. The ground floor is embedded into the sloping topography of the site. The separation into two main levels allows for the complete opening of the foyer with no need for climatic separation between inside and out, it enables constant circulation of wind along the slope. The large horizontal roof spanning over the teaching spaces and studios provides shelter against rain and with its generous cantilevers also offers sufficient solar shading to the windows. The open teaching-level also allows easy cross-ventilation while the skylight with integrated solar shading lets in enough daylight. The whole building, slabs, columns and the roof is conceived in concrete without cladding.

![]()

fig. 6

Architecture Faculty isometric

Hong Kong 2008

The mass of the concrete helps to balance the enormous temperature fluctuations in this extreme climate. As a project it explores a series of principles that combine, space, structure and climatic sustainability and allowed us to return to an important resource of architecture grammar characteristic of the tropical climatic conditions in the Asian, African or South American context.

JK

The title of this lecture comes from mathematics ‘the principle of insufficient reason’. It’s a renowned statement. I’ve noted down five terms that are relevant in my work and I’m going to read the definitions of those terms, which I found on the Internet. The title, which I also found on the Internet, is described as: “The principle of insufficient reason states that if the ‘n’ possibilities are indistinguishable except for their names, then each possibility should be assigned a probability equal to ‘1/n’.” That just means that whatever occurs has to have a reason. Then I started to think about what my reasons could be for making things this way and not the other way. So that’s how I constructed this talk.

The first theme is ‘beyond culture’. The first two projects I’m going to show fit in this category. The Wikipedia definition of the word culture is: “The cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history.” I don’t agree with this definition, and the first project is in a sense an antithesis to culture because it consists of the two basic archetypical structural forms found in European architecture, the cupola, the Roman arch, and the beam, Greek trabeated construction. They’re combined without any interrelationship, one on top of the other, and then these two European archetypal architectural forms are exported to China like this.

![]()

fig. 7

Cultural centre competition model

Shenzhen 2008

The second project is a competition in Switzerland that we won five years ago. The aim of the project was to propose a housing typology that didn’t exist, that it shouldn’t be like anything that you could quantify as a type, not like a detached house, not like a row house. What we did was choose a number of volumes, square tall ones, rectangular flat ones, oblique ones, all mixed up. What’s interesting about this, if you look at the apartments, is that they all have different kinds of outdoor spaces with views to the back, to the front, to the side, and so on.

![]()

fig. 8

Housing competition interior model

Switzerland 2007

The result is a complex and diverse mutation of apartments. What’s also interesting about this project is that there are some volumes that don’t have stairs because they’re accessed by the other volumes. And it’s beyond culture because it doesn’t refer to convention. It breaks convention, and the result is a series of unexpected relationships where apartments look into each other. It creates spatial connections from one apartment to the next.

The second important aspect of my work is ‘technology’: “Technology is the usage and knowledge of tools, techniques, crafts, systems or methods of organization in order to solve a problem or serve some purpose.” I’d like to quote the abstract of one of Laurent Stalder’s thesis projects: “The appliance house describes a concept of architecture that dominated architectural discourse throughout the ‘long’ twentieth century. [...] Ultimately, it will be a matter of considering the implications of the replacement of the classical definition of architecture as a fixed, enduring construction with that of architecture as an environment in constant flux. [...] The architecture of the avant-garde, so the basic premise here, is read as a concrete response to changes in the state of technology and ideas of society.”

This is a building that will start on site this year (2012). There are three apartments on top of each other and it basically consists of an elevator and a stair. It doesn’t really have an entrance, it doesn’t really have a basement and it doesn’t really have a roof, or a roof with a space in it. It’s a twelve-metre square with an elevator just off centre and four columns on the elevation.

![]()

fig. 9

Apartment building

Nidau 2009-2015

Photograph by Georg Aerni

There is a six-metre window that opens to allow access on to a large balcony, and on the corner there isn’t a mullion and the window opens another three-meters in the other direction to create a totally free corner.

![]()

fig. 10

Apartment building

Nidau 2009-2015

Photograph by Georg Aerni

To enter the building you drive down a ramp to the underside of the building and then you access your apartment by elevator.

The third term is ‘principle’, again from the Internet: “A principle is a law or rule that has to be, or usually is to be followed, or can be desirably followed, or is an inevitable consequence of something, such as the laws observed in nature or the way that a system is constructed. The principles of such a system are understood by its users as the essential characteristics of the system, or reflecting system’s designed purpose, and the effective operation or use of which would be impossible if any one of the principles was to be ignored.”

The fourth theme is ‘structure’: “Structure is a fundamental, tangible or intangible notion referring to the recognition, observation, nature, and permanence of patterns and relationships of entities. The description of structure implicitly offers an account of what a system is made of a configuration of items, a collection of inter-related components or services. A structure may be a hierarchy (a cascade of one-to-many relationships), a network featuring many-to-many links, or a lattice featuring connections between components that are neighbours in space.” What’s interesting is that these are not architectural terms, they are just definitions from a dictionary, but they sound architectural. This is a competition project we did in Geneva. It’s a university campus building that is vertical. What interested us in terms of structure is that the building programme is made of big spaces like auditoriums and small office spaces, big spaces like libraries, informal zones where people could meet, a restaurant or café. The aim was to develop a structure that is not repetitive or demanding that a space fits exactly in a grid, but that the structure, or the columns, follow the lines that are required by the spaces.

![]()

fig. 11

Office building competition model

Geneva 2008

So if a space needs to be without columns then they deflect to the sides of the big spaces. This forms a building that is large and deep which was a problem for the upper floors with the offices, so the building had to become narrow at the top and remained fat at the bottom, and the structure follows this logic. Another small project within the ‘structure’ theme is an extension of a hotel that I’m working on at the moment. It’s essentially a one-space addition, kind of a veranda for an existing hotel with just one column that is at an angle.

![]()

fig. 12

House extension

Seelisberg 2009-2015

Photograph by Georg Aerni

It’s at an angle because I wanted the space to be oriented to the outside, to the great views of the mountains. It makes the space feel as if it’s leaning to the outside. The structural roof is vaulted because the column is toward the back of the slab. In the intermediate floor the column is in the centre and doesn’t needs this kind of articulation.

![]()

fig. 13

House extension

Seelisberg 2009-2015

Photograph by Georg Aerni

The top slab needs reinforcement because of the cantilever. The vaulted space that results is determined by the structural decisions that I made.

The last term is what I call ‘classic’. The term is a provocation because it relates to a house that I just finished for my brother: “The word classic means something that is a perfect example of a particular style, something of lasting worth or with a timeless quality. The word can be an adjective; a classic car, or a noun; a classic of English literature. It denotes a particular quality in art, architecture, literature and other cultural artefacts. In commerce, products are named classic to denote a long-standing popular version or model, to distinguish it from a newer variety. Classic should not be confused with classical, which refers specifically to certain cultural styles, especially in music and architecture.” The concept model for the house was a post-it-note, and the thing about post-its is that they have a sticky side and a loose side. In this space structure and space again form an entity and the final house looks just like a big post-it-note.

![]()

fig. 14

House for brother

Langenthal 2011

Photograph by Dominique Wehrli

SP

Rolf, the work you do with Studio Basel is interesting in the context of Switzerland. Switzerland is a country with a cellular structure. By that I mean that it’s formed around a democratic concept where the individual still has a stake in political decision making through the municipalities (2636 as of 2009) and the governance of the cantons. It means that there’s more architecture produced locally and in contrast it means that any concept of urbanism is necessarily limited due to the same political constraints. So, where does the impulse to study Switzerland as an urban phenomenon, in the first instance, but then also all these other cities around the world, come from?

RJ

I will try to respond but I don’t just want to answer your question in the context of Studio Basel because of course it also applies to our own work, and we are here to talk about our work. You can say that there are certain influences that come from Studio Basel and that’s also why we showed some of the images at the beginning of the lecture. What we tried to emphasise was a way of working that is based on observation and not just the collecting of data, not to look at these problems in a statistical way but rather to really understand the mechanisms behind cities. It’s a much more phenomenological approach. The founding members of Studio Basel, Herzog & de Meuron, Marcel Meili and Roger Diener, they all studied under Aldo Rossi, who, when he was teaching at the ETH in Zürich in the ‘70s, created a sort of environment where he taught his students to really observe real phenomena. For instance, they had to draw a map of Zürich showing the ground floor plans of buildings, the different areas and quarters of the city, to understand the relationship of this ground floor with the urban spaces, how spaces are used between building and so on. I can’t go into great detail because I wasn’t there. But it was a really strong influence on these four people, and their work, and they brought it back to the university when they founded the studio in Basel in 1999, I think it was. I think it’s very interesting, because they’re architects, they’re really architects who brought their very own way or approach to look at the city. As we said, they are not economists or sociologists, but are really looking with the eyes of an architect. It’s quite interesting what appeared out of this method of looking at things. For instance when we establish a studio, it’s really about defining different threads so we can begin to understand an urban condition. We force the students to first define it from a very perceptive perspective, to take pictures, to look at how people are living in these spaces. I think this also influences our own approach when we work on urban design projects. It really is about first of all trying to understand the conditions in which we work, which is not only about the physical aspects of the building but also other background factors.

SP

But these observations nonetheless produce architecture, which superficially at least, looks modernist or like buildings produced after the war. I wonder if the observations actually inform your architecture because your work looks ostensibly modernist. Are the three of you consciously pursuing this look?

JK

You said all three of us, but I disagree that I’m doing that. I’d like to distance myself from this.

TW

What would you like to distance yourself from?

JK

From the modernist architecture from the ‘50s and ‘60s. I think it may be a starting point because I think the ‘50s and ‘60s was an interesting period. But the way I see my work, this may be a starting point, but I consider my work more free than that. I think that my work is not as repetitive as the structures from that period. It’s more about exceptions and increased knowledge in engineering, larger and wider spans, less serious formal connotations, more provocation and playful elements. So from my side the modernist vocabulary is not something that I intentionally evoke. Before the talk we were talking to each other and we said that maybe we are too close in the way we work, that we’re very similar, but this is maybe one of the differences. I mean, the projects I did ten years ago were even more chaotic, so I don’t come from this background. I consider Tom and Rolf’s work much more organised than my own work. And my work is not really about urban issues and less about social aspects. Maybe that’s the difference. I’m not someone that says this is not good enough because I want to better the world. I can’t provide this. The only thing I can do is to hopefully produce beautiful buildings. I think in my work I try to find things that are not obvious. One of my first points in the lecture was about ‘beyond culture’. When I stated this anti-typological idea, it was about the competition we did for one hundred and fifty apartments. Our entry was a reaction to the Swiss competition system in which hundreds of apartment buildings are created that simply follow a certain ‘type’. You can open any page of a magazine and see one of these apartment buildings, and they would all be above average. The Swiss do this. Architects in Switzerland are very good at developing types in a standard kind of way. What I wanted to do was to find something that was not typologically definable. So we ended up with this chaotic arrangement of different volumes and worked hard to fit apartments into this complicated geometry. The outcome is a surprising variety of strange apartments. And the fact that it hasn’t been built is part of this problem because it’s too complicated, it’s too expensive, and it doesn’t give the investor the return that they’re looking for. That’s another reality we have to face as architects. It’s very challenging to build something out of the ordinary. But if we don’t try to create something ‘out of the ordinary’ then who will? I’m not happy with the repetition of the existing status quo. It’s just not my mentality.

RJ

In Switzerland there are many approaches in the different parts, the French and the Italian. The influence of the ETH in Zürich is enormous at the moment. There are a lot of young practices that start after just having graduated from the school, which is quite interesting because they are really trained academically and then immediately adapt to practice through the competition system. They graduate and they are perfectly capable to develop floor plans. You can also see that they are very strongly influenced by the teachers at the school who at the moment deal with the more conventional aspects of architecture and have quite a conservative background. I’m not making a judgement one way or the other, but you can clearly see that there is a tendency in architecture toward a more conventional or conservative approach. This means that there aren’t many experimental works happening at the moment, there’s not really any radical criticism of those conventions. And I think to go further in architecture this has always been important. We attempt to make this criticism in our work.

SP

But the radical in your work and Jan’s is very different. To conceive a building from type or a post-it note comes from a totally different way of looking at things?

JK

Rolf and Tom’s work has a different approach because it doesn’t fulfil the criteria that are required to build in Swiss cities. From this point of view their work is making a radical statement. You can’t propose an apartment building like the cross-shaped one in Nyon and expect it to be built. It’s just not possible. So this is their approach. For me architecture is not just a random assembly of disconnected parts. Things at a small scale have a physical logic that can also exist at a large scale. If I have a security clamp this is not a building, but it is a structure that exists made of real materials and with a real function. The post-it, the way that it stands, folds, the space it creates is a reality made from real material, and when you photograph the space underneath it, then you get exactly the space I was looking for in the house. Something that is small can also exists as something large and vice-versa. From me there is no distinction between a shoe and a building, there’s no difference between a napkin and a building, they’re all material and they all have their rules and regulations and material qualities. If a piece of paper stands on four points that are folded, then the building will do the same. It’s a little bit provocative and a little bit ironic but it’s also serious. I mean, what’s the difference between this glass that I’m holding and a Brancusi sculpture, you put the glasses on top of each other and you get a Brancusi sculpture. This is something that is very important in my work, because I never see a building as having a detached material reality. I always see it as an existing spatial condition where each part belongs to another just as it does with the sleeves and buttons of the jacket I’m wearing, or the shoes that I’m wearing. Of course there are good and bad shoes. I like things when the structure, material and space come together to make one entity, to make one element. The post-it is one element, it’s a whole. The post-it is also in some way a universal object. It doesn’t change according to its context. I don’t design local. I don’t see the world as a set of different contexts. I think it’s one world, it’s one place, and for me context and these relationships are meaningless. I like Brazilians as much as I like the Swiss, so why should I build Swiss houses in Switzerland and Brazilian ones in Brazil? The thing is, if I say I’m interested in making a project for China, I could go to China, look around and make a building that will be a kind of pseudo-Chinese building. If I were a traditionalist I’d go there and look at the context. But this isn’t my approach. Instead I thought of what could be exported. I thought of the archetypal Roman and archetypal Greek construction types that make Europe so fantastic, I put them together and exported them to China. I’m not saying this is the right answer but it’s just a comment on this global phenomenon. I try to be honest, to make an export product with these characteristics. You could also say, I want to do a pagoda to fit in to the context, but since both are intellectual constructs then why not create something that means something to me. For me beauty is very individual. I think it’s a feeling more than a reality and I think that every human being has a different sense of beauty. The first premise for me is to make something that I like. The rest I can’t control. That’s how I define beauty, because I like it, I made it, and now I learn from it, and I find out what I like and what I don’t like, and next time I’ll do it better. I’m the measurement of beauty and nobody else. I can describe my sense of beauty as the search for the ‘entity’, and the ‘entity’ is something I can find in a well-made instrument. The violin is made of a material, and it sounds good because it’s made of that material, and it’s an extremely beautifully crafted piece of culture. I hope my buildings have the same qualities. I’m too stupid to create something complex, so that’s why I start with a piece of paper. That’s why I do it this way. I only do things that I can control, and I can control a piece of paper. This is the level of complexity I can control and make sense of.

TW

For Quatremere De Quincy ‘type’ meant the reduced essence of the idea of a thing. So we could also talk about types of objects, like this glass I’m holding, that are vessels for liquid. It doesn’t really suggest a form or shape. We are quite strongly influenced by the work of Oswald Mathias Ungers from the mid 20th century. In the ‘80s he commented on the idea of ‘type’ that Aldo Rossi described twenty years earlier, and we agree with Ungers, that ‘type’ is not a design tool but rather a tool to analyse something, to categorise it. Rossi used the word model to describe the precise shape of something. Jan’s apartment building is not designed using type as a basis to design, he hasn’t used precedent, but actually if you look back at the history of architecture there are similarities to other types, with stacked apartments on top of one another, with more or less random plan organisations, the work of Tony Garnier for instance, who designed these strange apartment buildings, if you take away the angles, which are not orthogonal, then you can say that there are already a recognisable types in Jan’s design. But it doesn’t mean that he used it as a method to make the design. This is quite important. It’s an analytical tool. But our interest lies in exploring what it means to create a ‘common’ architecture.

RJ

As I said earlier, we also use a more phenomenological approach that comes from the way the professors at Studio Basel present their ideas. This is perhaps a more tentative way of looking at a context. Here we make a distinction between the idea of architecture as a completely autonomous discipline, from which the idea of ‘type’ comes from, and those who think that architecture is a generator for social change. We are less interested in trying to bring the two together as a method but see the benefit of being able to analyse a context and to understand its mechanisms without proposing that it can be used in the design process. We don’t think there’s a direct link.

SP

Are there any questions?

AUDIENCE

Yes, this is for Rolf and Tom. The way you represent and appear to explore your projects is through collage and axonometric drawings, which seems to me to have a strong relationship with how heterogeneous programmes are stacked in various layers, in the urban project, with the superimposition of two cruciform buildings into a very mixed or diverse context, maybe ordering is the wrong word, but certainly heightened the contrast between the individual houses and the different sorts of public space or private space that was defined by the rooms made by those wings. On the other hand you made reference to aspiring to strong form. From the literature that I’ve read from the period when Swiss architects were making the boxes that they became famous for, there are a lot of references to strong form and therefore to gestalt theory. To use Jan’s phrase, the things were always referring to themselves and became very object-like. My question is how you bring together the aspiration to create strong objects, a very complete object that refers to itself, but at the same time accepting incredibly heterogeneous programmes, or very heterogeneous urban environments?

TW

Not to confuse things, we don’t always want to produce strong objects. This was really only discussed in our section on how to produce public buildings. But it is also a good way to make buildings legible for people, in a way that everyone could understand or grasp. In our town hall project it was very explicitly about making something common and we don’t necessarily attempt do this in every project, or to make strong forms out of every programme. I think that you can also see from our section on typological thinking that strong form is not the only issue we’re interested in.

RJ

I think it’s interesting to compare the difference in the way we work. We like to look at the relationship of things, Jan the inherent logic, the structural logic without trying to relate it to the context. We try to relate to the context by abstraction. The Swiss box is now a cliché. My understanding of the Swiss box is that it really has nothing to do with discussions of the urban context; it’s only focussed on the perfection of the object itself, and there we are different, because we are interested in the relationships that are created through the abstraction of form, whether through a cross-type or a circle, between these simplified spatial bodies and the context that surrounds them. We are interested in ‘framing’, and how buildings can develop as a background for very heterogeneous conditions, which within the urban context are actually a reality.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()